[Image: Tom Vigar, "Subtpoian Dreams" / Project Text.]

[Image: Tom Vigar, "Subtpoian Dreams" / Project Text.]A few weeks ago our compadres at

InfraNet Lab posted a brief to a

conceptual project that they say envisions “The military-industrial complex and the suburban-industrial complex unified in marital bliss.” Upon first glace, I actually misread

marital for

martial, and in this case I’m not entirely sure that makes too much difference. Nevertheless, it sounded abysmally frightening. Yet, as it turns out, it's quite comedic.

The two (suburbia and militarism) have long shared an intimate relationship, as

Tom Vigar, from

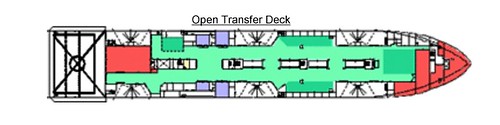

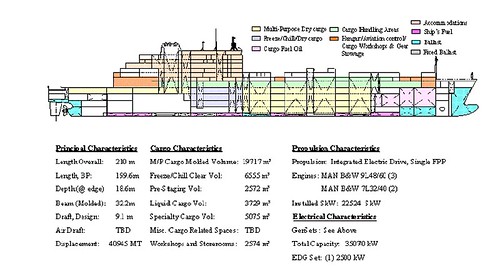

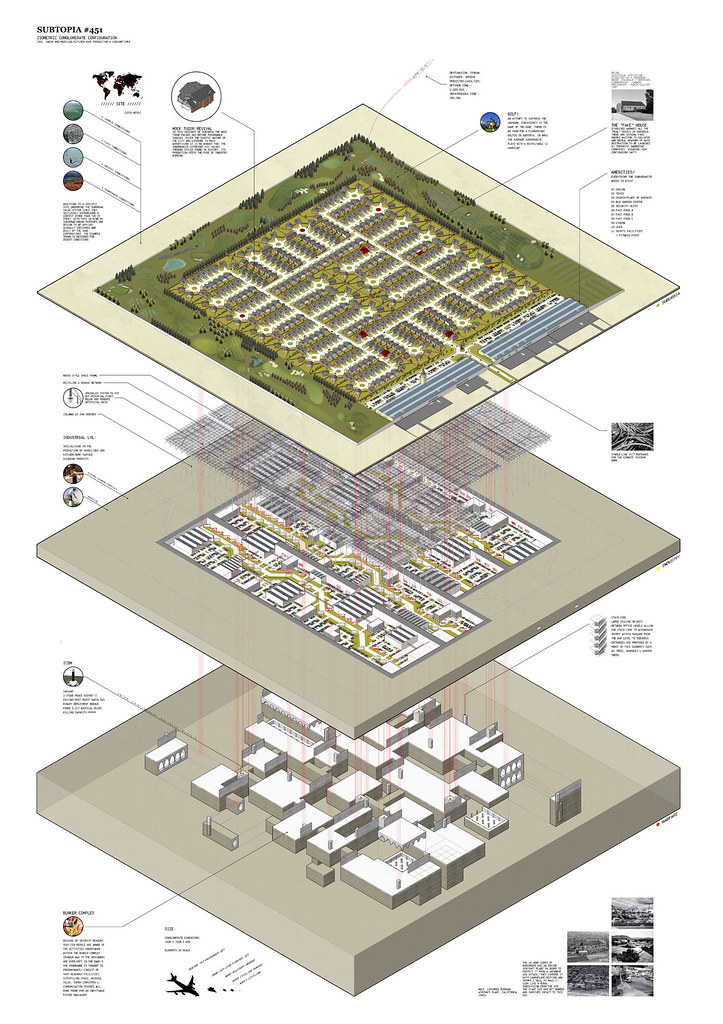

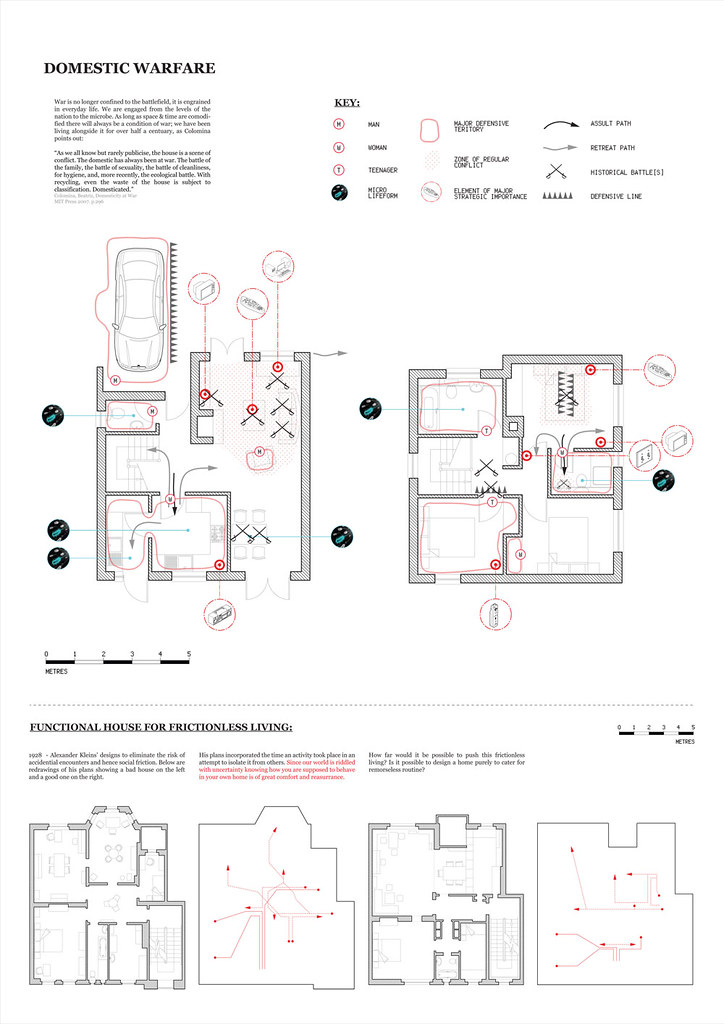

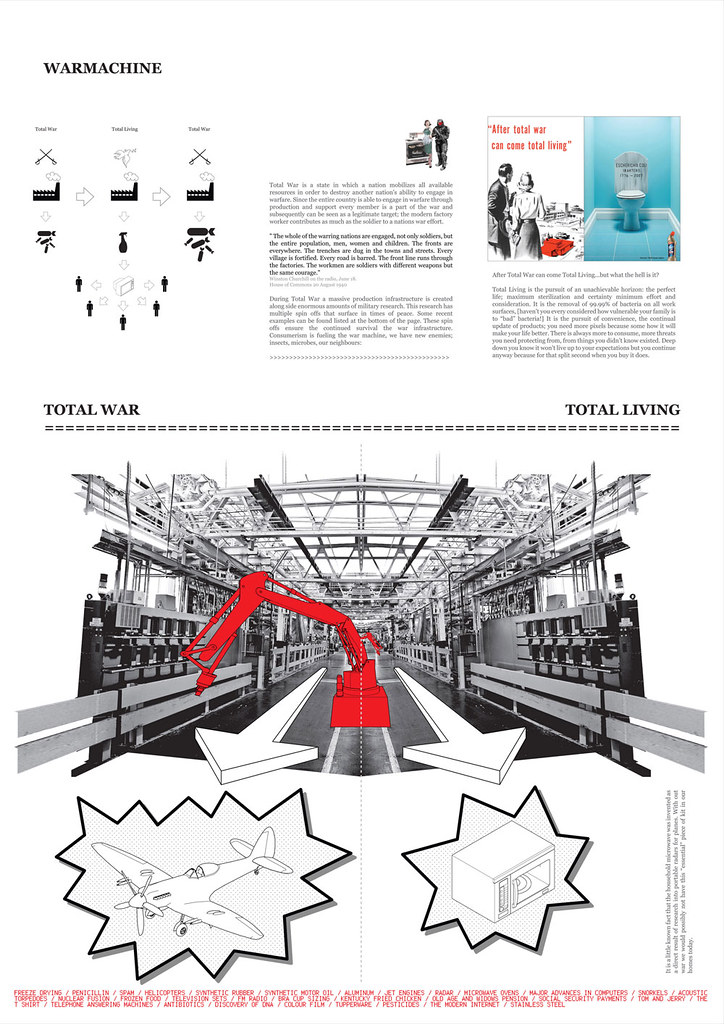

Scheffield University, reminds us in his project

Subtopian Dreams – a sardonic proposal that renews the spatial vows of suburbia and militarism together to reconstitute the war machine’s optimal baseworld landscape, one that would take advantage of their pre-existing interdependence and, as

InfraNet puts it," share the same territory in a cyclical symbiosis."

[Image: Tom Vigar, "Subtpoian Dreams" / Project Text.]

[Image: Tom Vigar, "Subtpoian Dreams" / Project Text.]Reading through an

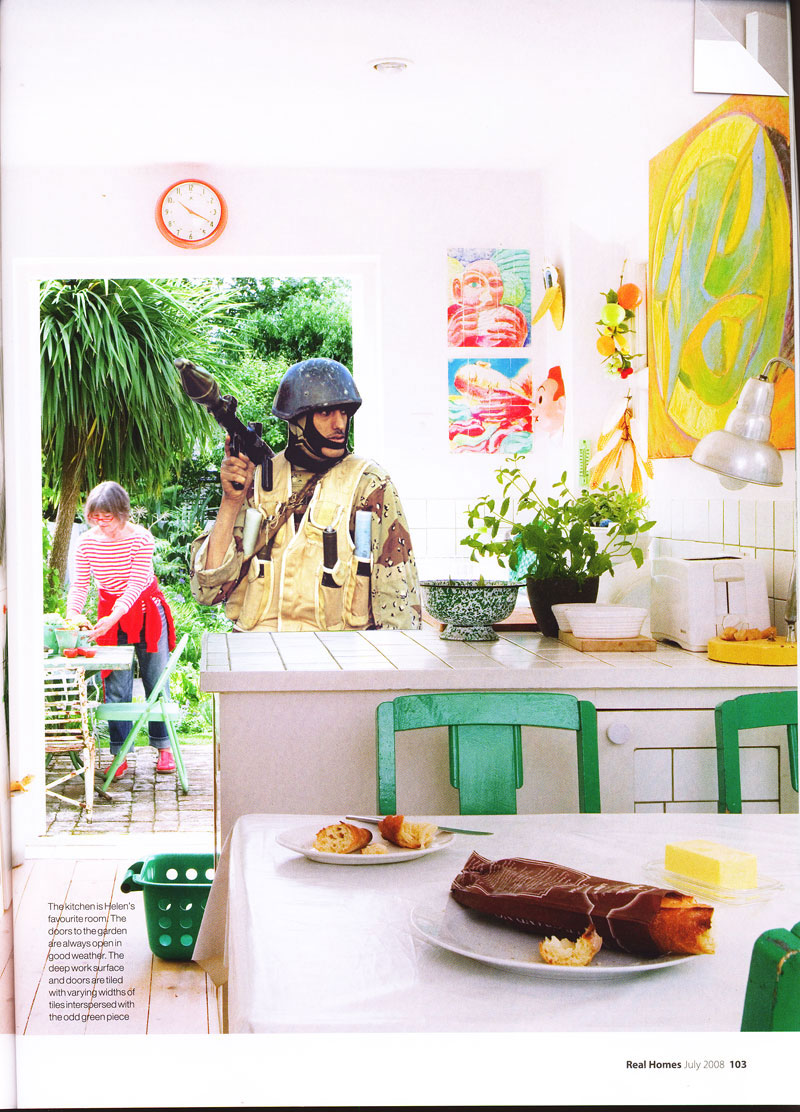

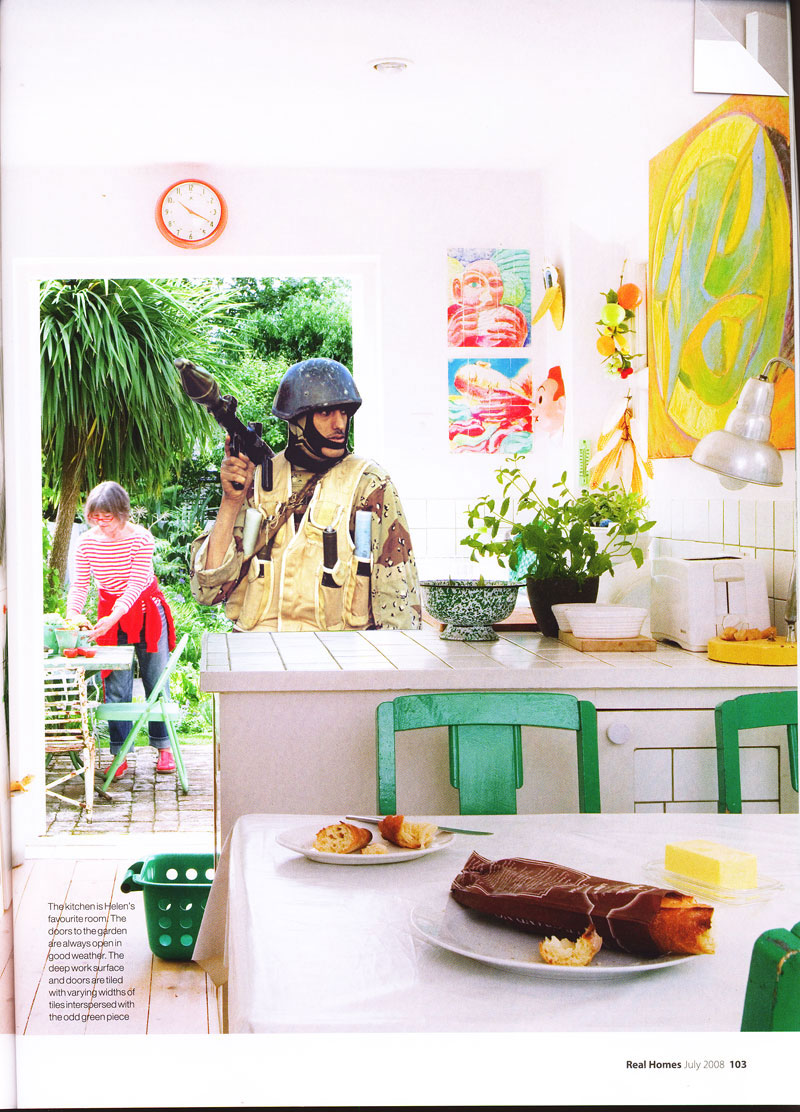

extract Vigar provided for the curious minds over at

CTLab, one gets the feeling he has fancied numerous times an exquisite bombing campaign over the American suburban landscape (who hasn’t? … and, lets’ face it – the burbs just seem so blissfully ignorant in their insular world that sometimes it’s tough

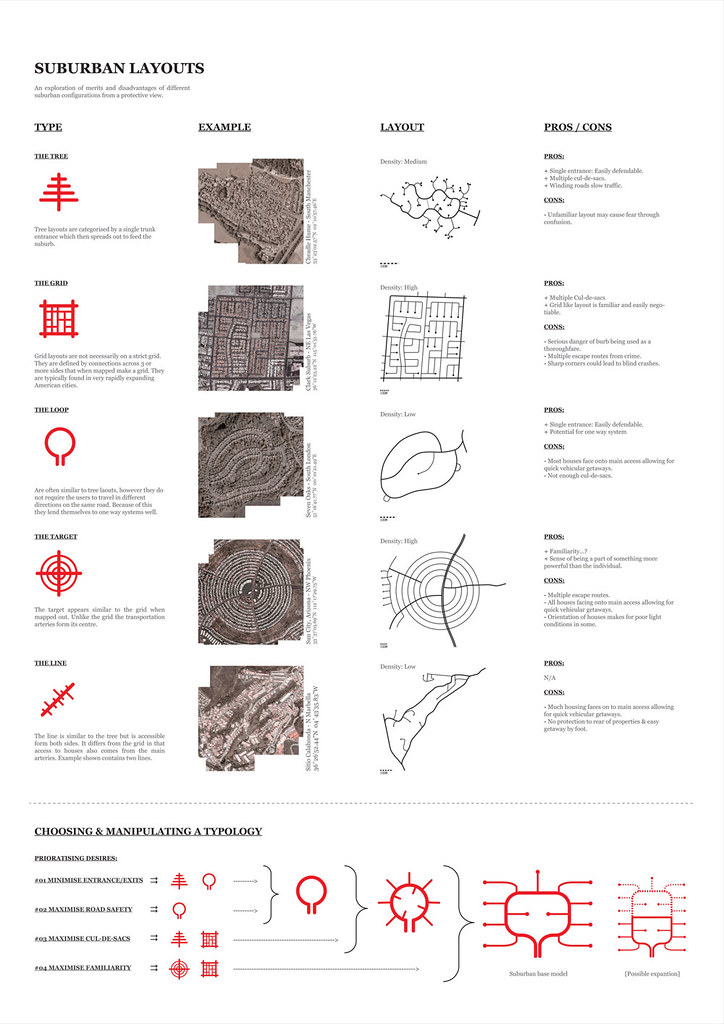

not to think that maybe only bombs could save the terminally vapid from themselves). Yet, perhaps responding to a knee-jerk fantasy of completely leveling America’s swaths of pretentious oasis, he has decided instead to err on the side of sarcasm by proposing a suburban model that is both honest in reckoning with its relations to the war machine, while perhaps taking pity by giving it some good old-fashioned defensive posture.

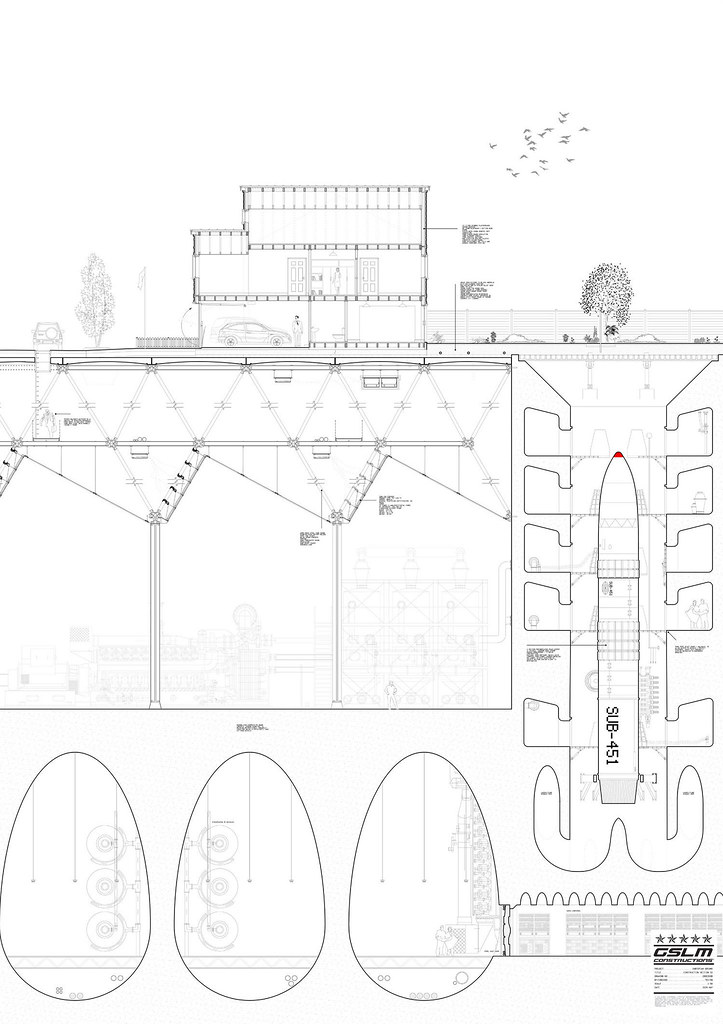

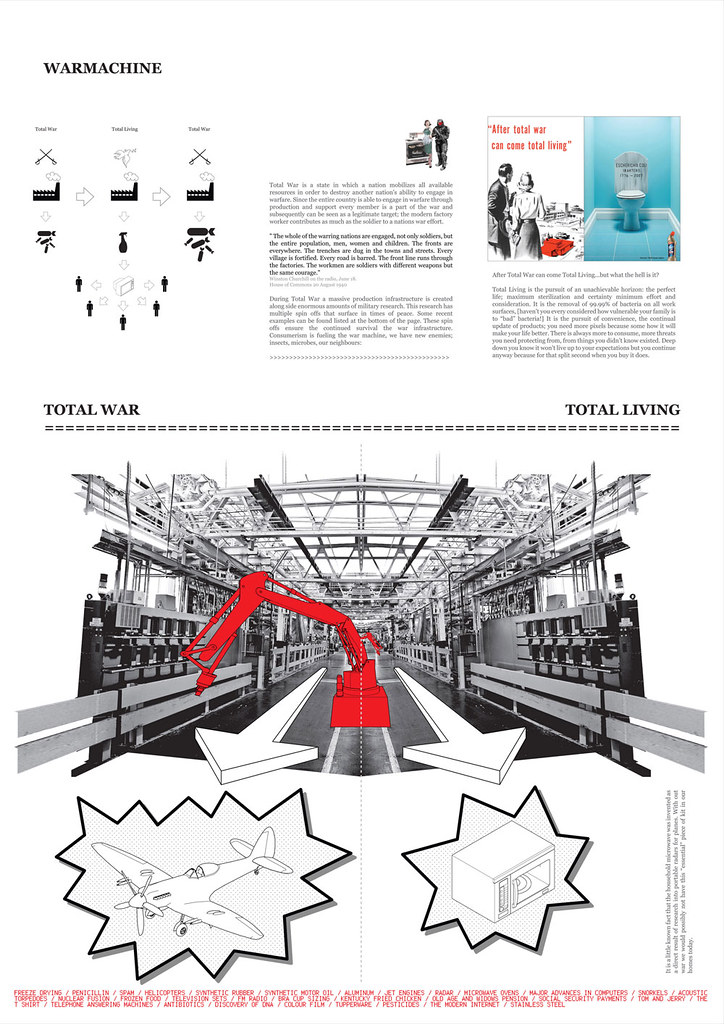

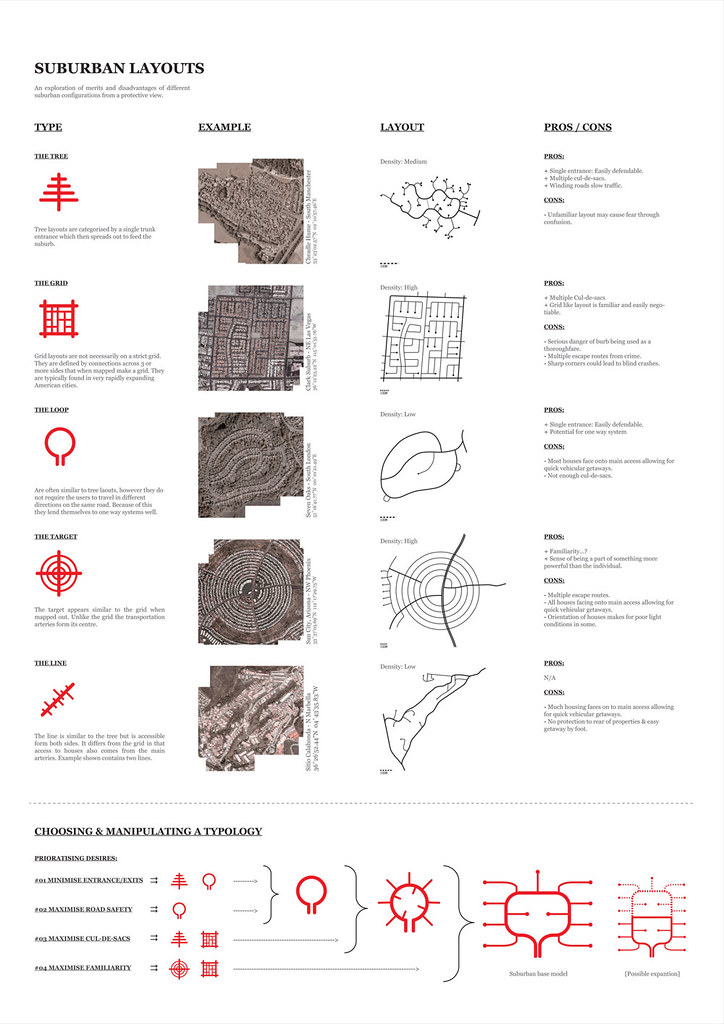

His plan is to relayer the industrial archeology of suburbia with more direct military underpinnings in order to seize upon the economic and infrastructural elements that are already at work there – bringing together manufacturing, consumerism and the military itself under a single roof in order to fully realize suburbia as an ideal engine for the space production of war’s preparatory landscape.

[Image: Tom Vigar, "Subtpoian Dreams" / Project Text.]

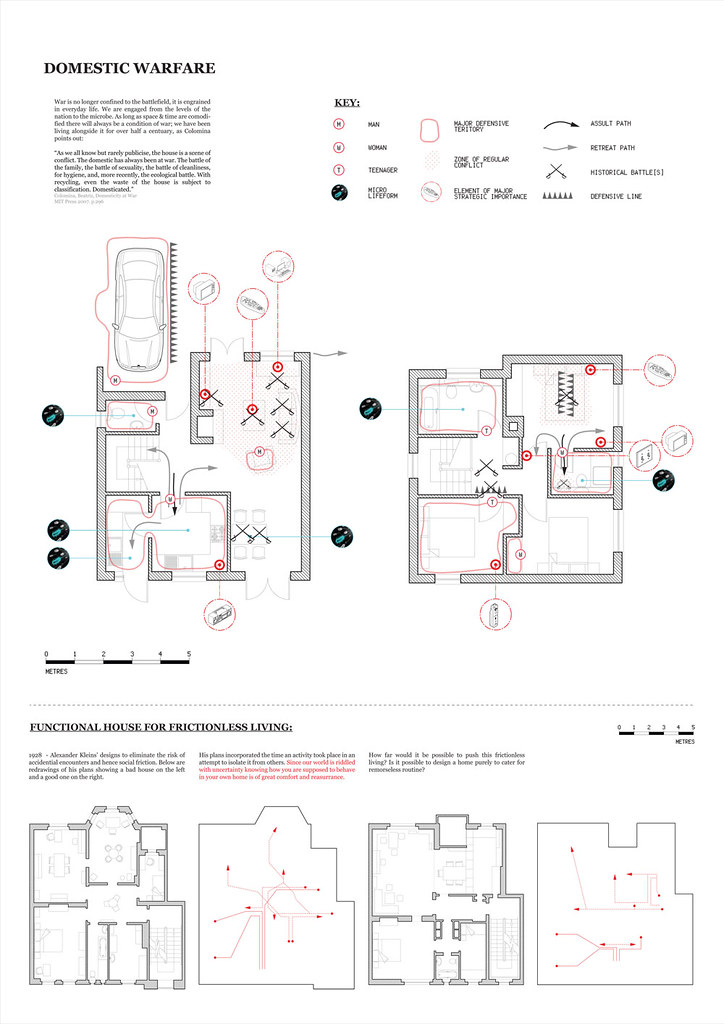

[Image: Tom Vigar, "Subtpoian Dreams" / Project Text.]Riffing off of Virilio’s notion that the annihilatory realities of military superpower and evolutionary warfare have rendered a war that “is no longer in its execution” but rather in constant “preparation,” –- or, a state of perpetual war (“Pure War”) – Vigar writes:

The question for any powerful country should thus no longer be how we can actively [and geographically] neutralise a potential threat, since it can come from anywhere and is often aspatial. The question should be how we can engineer a situation whereby it would be unacceptable for enemies to attack us and would result in immediate and prodigious counter attack. In other words: How can we maintain the Total War infrastructure during times of Peace?

The idea of maintaining an apparatus for constant war during times of peace is obviously an oxymoron – can peace ever be truly achieved if the ability to wage war is always churning and perfecting itself in the background? Is it a self-defeating task to try and simultaneously wage peace but ultimately prepare for war at the same time? How can geopolitics settle on cooperation when the larger economy itself is founded on the consumption of military products? It's the central irony of our times. Regardless, the answer in fact is that the ‘total war’ infrastructure is already firmly in place; it's been rooted in suburbia perhaps ever since its earliest origins outside post-industrial London when a new moneyed class sought to disentangle itself from the wretched intermixing of the classes and compressed laborspheres in the city. With their retreat they generated a lifestyle and suburban pattern that has as time's gone on, Tom suggests, placed the suburbanite at war with everything around himself from his neighbors to nature to terrorism alike. Quoting him further:

The chemicals we spray on our lawns, the vast array of wipes, gadgets, brushes and engines we buy help keep the manufacturers at a state of readiness for war unsurpassed in history. The real beauty of this system is that the suburbanites, for the most part, are blissfully unaware of its existence. Suburbia is a political armchair, complete with electric massager and six can beer fridge, placed squarely in front of a 42-inch plasma flat screen TV. Suburban Living with all its intentions of escaping the chaotic nature of the city is actually facilitating a state of warfare through its remorseless consumption and political detachment. In turn this Pure War accelerates the fragmented nature of the city: One could easily argue that many terrorist attacks are a result of it.

There are, of course, other deep reciprocal bindings between militarism and suburbia. In Mark Gillem’s book

America Town: Building the Outposts of Empire

, we are made dutifully clear on how suburbia more directly territorializes foreign soil, not only in the banal spatial patterns of the suburban identity that is routinely exported to other countries seeking to create an

America-town on their own turf, but in the ways the suburban model is egregiously incorporated into the planning and design of U.S. military bases abroad, which brings an uncanny sense of familiarity to the soldiers there, so that not only do they feel they are fighting for home but they are fighting more directly

from home.

[Image: Tom Vigar, "Subtpoian Dreams" / Project Text.]

[Image: Tom Vigar, "Subtpoian Dreams" / Project Text.]The suburban design of foreign military bases brings a little slice of the homefront to the frontier – a frontier that is today more akin perhaps to a series of islands and amorphous geographic connections rather than the Westphalian linearity of militarization along the edges of the nation state. The frontier today is not a border so much as an archipelago of occupied zones.

Thomas Barnett in a recent interview about his latest book

Great Powers: America and the World After Bush

says what we are experiencing globally today through geopolitical conflict is a greater integration of the frontier; globalization, he says, is like the American push westward during the 19th century.

However, I tend to agree with John Robb’s

assessment that the frontier analogy suggests a tier system through which the rule-sets of the colonizers and ruling elite are disseminated and negotiated across the plains, and today the rules of colonial ordering from the top appear to be in a state of dissolution while enforcing a more widespread subset below. So, as globalization expands its system to wider global markets the logic at the core of this system begins to thin and lose integrity. Though, what the hell do I know, I certainly admit, I'm a bit out of my league in that conversation.

[Image: Tom Vigar, "Subtpoian Dreams" / Project Text.]

[Image: Tom Vigar, "Subtpoian Dreams" / Project Text.]But I wonder, if suburbia, gated communities and military bases are the outposts of empire, then what does this loss of executive integrity mean for the politics of the field office, so to speak, and the system that it spreads?

Gillem draws plenty of parallels between the suburban models at home and the planning of military bases abroad, the disintegration of their social values (or, rather the prefabrication of social value), and the policies of fear which stoke their greater low density planning and sprawling design. All this feeds a need for further excessive land use, closer partnerships between the infrastructures and economies of suburban manufacturing and the military machine, which only helps to swell American ethnocentrism through a strategic sense of architectural and cultural familiarity. And where there is familiarity on one side, there is

unfamiliarity on the other, and so the ultimate product of suburbia may not be just its self-projection but a projection of what it is not.

The American suburb and the foreign military base are both places that “bring together diaspora communities searching for spatial familiarity,” Gillem writes. “The buildings and neighborhoods both expose and obscure economic, political, and social priorities.” The perfect conditions for Vigar’s

proposal since it capitalizes on the sheer aloofness of suburbia itself.

[Image: Tom Vigar, "Subtpoian Dreams" / Project Text.]

[Image: Tom Vigar, "Subtpoian Dreams" / Project Text.]Suburbia posing for the military base gives both places a sense of entitlement and triumph, not to mention cultural superiority through spatial affinity; so the typical suburban resident feels the same sensations as the soldier the other side of the world walking through their respective neighborhoods, and vice versa – they both march to a sense that their space is the ideal space and from there it should be expanded, and anything beyond that on the other side is not only different but spatially confused and culturally incomparable. This is the fear in familiarity, the dangers of home.

What are suburbs anyway but space in uniform? In fact, when one reads Gillem’s

book

it conceptually becomes a bit confusing to consider which actually came first, the foreign base or the suburb? Of course they each have their respective lineages, but at what point did foreign military bases begin to take on -- in a dramatic spatial sense – the near perfect image of their homeland? I’m no military historian, or a suburban scholar for that matter, but in their contemporary forms there is little separation today in their planning and development, not to mention in the social political distortions that idealize them similarly.

[Image: Tom Vigar, "Subtpoian Dreams" / Project Text.]

[Image: Tom Vigar, "Subtpoian Dreams" / Project Text.]Anyway, I’m rambling, but the military base abroad is nothing but an extension of suburbia and its economic interests at home, with onsite

Starbucks’,

Burger Kings, shopping centers, the low density model and rambling exclaves of consumption, split-level ranch homes, big box stores, and auto-dependent infrastructure, as Gillem’s

book

so eloquently traces. The industries that are largely invested in suburbia are heavily profiting off of the military base overseas, while suburbia is in turn the direct beneificiary of military excess and its technological transfer. In Vigar's own words:

There are many products that are a result of research and mobilisation for war; these range from the microwave to Tupperware. Nerve agents are no exception to this; research surrounding them has lead to the development of a whole host of new fertilizers and pesticides that are subsequently marketed to us as “must haves”: We need a perfect lawn in Suburbia because if we don’t have it we are somehow being a bad citizen. To maintain readiness for war companies have been forced to find uses for their products, often creating things that we don’t need, yet through advertising desire.

There is little distinguishing the two anymore from a corporate or military point of view. Vigar's project laughingly says, why not take this hideous ambiguity to a perfect sublime?

[Image: Tom Vigar, "Subtpoian Dreams" / Project Text.]

[Image: Tom Vigar, "Subtpoian Dreams" / Project Text.]Pointing to Ulrich Beck’s concept of “place polygamy” – Gillem writes, “while at their homes overseas, they are paradoxically separated from but tied to their home in America.” Sort of the opposite of an

imaginary geography, I suppose, but rather torn in between two places at once that are in experience identical. If one travels but exists in an undifferentiated sense of experience at the same time, is one really traveling? Creepy. It’s like another form of detention. We often don’t think about the spatial models that house soldiers and how they are in many ways trapped in their own brand of detainment -- like militarized reservations. Suburbia.

Anyway, it’s classic spatial conditioning stuff, but nowhere is the American suburb more influential than in the confines of the foreign US military base. Suburbia is in this regard simply a military spatial product. If this is the case abroad, then it’s hard not to consider what the implication may be for the same model at home, no?

Which gets us back to

Tom Vigar’s

project.

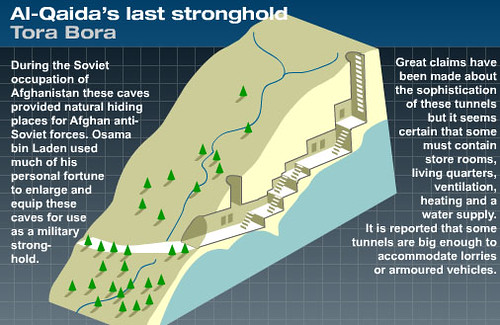

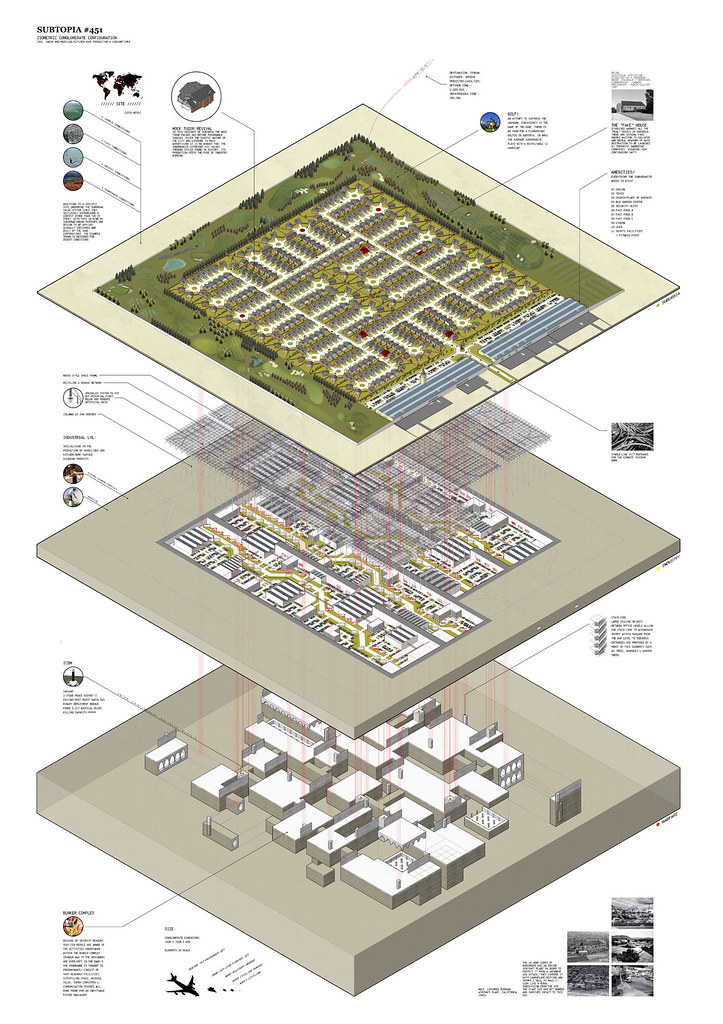

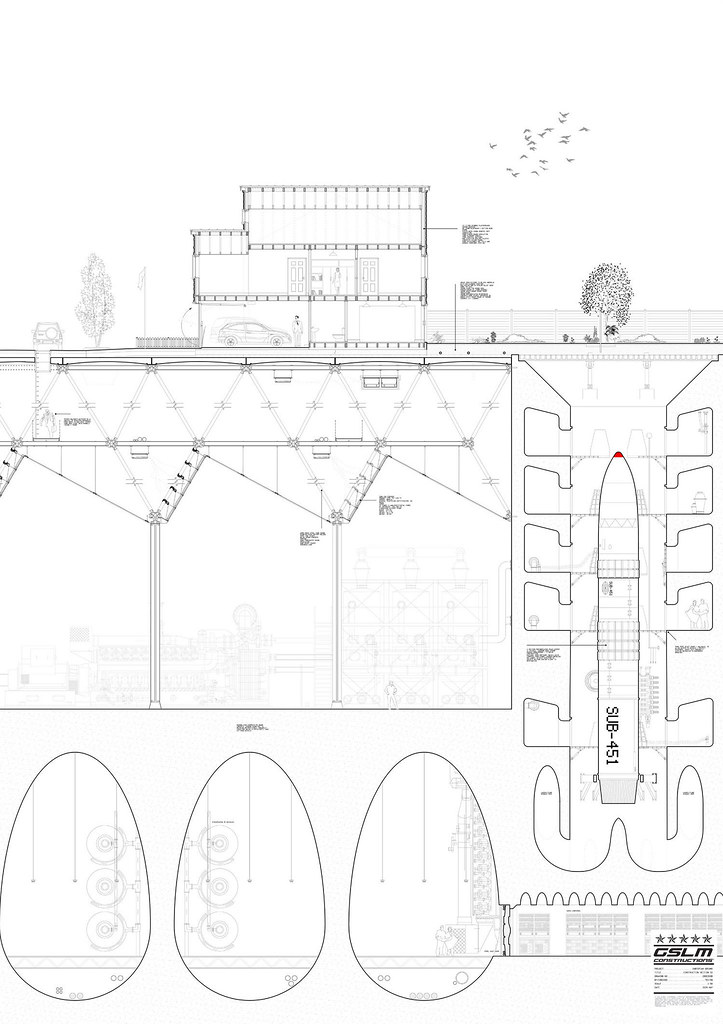

This project polemically proposes an inevitable, yet absurd, conclusion to the state of Pure Warfare that modernity has created. It postulates that Suburbia will eventually become the icing on a cake of industry and warfare. Not only will the products consumed by the suburbanite help indirectly support the war effort but the very suburb itself will become a shroud for the modern war machine. I propose the vertical stacking of the three separate plates of Suburbia, Industry and Warfare in an attempt to fully bring geography to its knees and make the already existing system far more efficient. The reconfiguration of these plates may appear to some to be a bizarre manoeuvre yet it brings forth multiple benefits:

He then lays these out: creating a more conservative manufacturng footprint, improving recycling industries, achieving more precise targeted marketing to increase residential consumption, hybernating bunkers, and even utilizing the aloofness of suburbia as a perfect human shield!

It’s a bizarre mix of design sensibility and brilliant farcedom. I love it!

As funny as his proposal for optimizing the suburban model as an imperial piston for the military machine may be, I’m not sure the war machine can be made to be more responsible or that it can be retooled to be more ecologically conscious, or rehabilitated in any way. That would go against its logic which depends on a constant reproduction of almost everything (including the “enemy”) and therefore waste, excessive consumption -- rampant expansions of power in all spheres. To cut back in any way would seem from the military/suburbia industrial-complex’s perspective a failure and a sign of its weakened state, its encroaching defeat, its terrestrial impotence. Which is of course why Vigar has moved the troops to the suburbs in the first place.

[Image: Tom Vigar, "Subtpoian Dreams" / Project Text.]

[Image: Tom Vigar, "Subtpoian Dreams" / Project Text.]If Vigar’s new military suburbanism utilizes suburbia as a massive human shield (which is a conceptual crack-up, by the way), then I wonder if the goal isn’t to secretly provoke war – because, since when did the “terrorists” spare the lives of their enemy’s human shields? Aren't these human shields the precise targets of terrorists themselves? Which begs another question: while his model might work in theory of Pure War, is it suited for the new dynamics of this “Global War on Terror” which ignores, or has rewritten to some extent, the classic target, the classic rules and engagements of war?

With the exception of the War plate each will have no idea of the existence of the others yet will be dependant upon them. The war plate will penetrate the other two in secrecy, ready to reveal its true nature at a computer calculated press of a big red button.

I envisage hundreds of these perfect suburban conglomerates scattered around the globe, each appears identical to the rest yet houses a slightly different War Plate. On the surface each condition of suburbia will deceitfully offer protection from terrorism, your neighbours, youths and pedophiles [depending on the current political climate] by systematically designing out the chances of their occurrence at the expense of public space and individual freedom.

The project is hilarious, and it makes me feel it is more subversively designed to get the military into war rather than merely keep it prepared in perfect blissful idleness. The best part is that it actually clarifies a lot of what are more accurate and truthful underpinnings of suburbia already, and how America-town has come to spread more alarmingly not only around the globe in the form of foreign military bases, but in the domestic military urbanism of lesser known towns and cities through out America as well.

[Image: Tom Vigar, "Subtpoian Dreams" / Project Text.]

[Image: Tom Vigar, "Subtpoian Dreams" / Project Text.]In her book

Homefront: A Military City and the American Twentieth Century

Catherine Lutz chronicles the militarization of Fayetteville in North Carolina, where the U.S. Army’s Fort Brag essentially garrisoned the entire community for the purposes of training, economizing, and expanding its base of operations ramping up for the “War on Terror.” She leads into her research with this quote which seems salient here:

“Much of the history and contemporary reality of war and war preparation has been invisible, though to people both inside and outside the military—because it has been shrouded behind simplified or propoganda, cordoned off by secrecy laws, or been difficult to asses because so many of the consequences of running our military institutions are not obviously war-related. And so we have not evaluated the costs of being a country ever ready for battle. The international costs are even more invisible, as Americans have looked away from the face of Empire and been taught to think of war with a distancing focus on its ostensible purpose—“freedom assured” or “aggressors deterred”—rather than the melted, exploded, raped, and lacerated bodies and destroyed social worlds at its center. And we have been taught to imagine the costs of war as exacted only on the battlefield and the bodies of soldiers, even as veteran’s injuries and experiences get scant attention, and even as civilians are now the vast proportion of war’s clotted red harvest.”

As suburbia and the military base become inextricably one and the same in the end what Vigar has laid out may be neither suburb or base, but some ambiguous bit of seamless landscape graft that is already sufficing as both, but taken now to its logical and fiendishly absurd extreme. A base that uses suburbia for cover, a suburb that is really a base, either way they're everywhere now.

Check it out:

Tom Vigar,

"Subtpoian Dreams" /

Project Text