In the Business of Blast Walls

A blurb in the Baghdad Bureau the other day points us to a busy blast wall factory operating in the small town of Gopola that “lies between Kirkuk and Sulaimaniya on the safer, Kurdish, side of the checkpoint marking the boundary between the semiautonomous Kurdistan Regional Government and the rest of Iraq.”

Yup, another black chip of peripheral real estate I’d love to tour one day.

Glimpsed through trees from the highway, the storage yard at first seems to be a do-it-yourself medieval fortress: scores of watchtowers, blast walls, sentry posts and barriers are stacked up in a field ready for delivery to whichever home, compound or neighborhood is next to be sealed off from the outside world.

Gray, featureless and crudely built, these blast walls have become the most readily identifiable symbol of the current state of Iraq, replacing the endless lines of cheap, mustard-colored walls emblazoned with eight-point stars that used to surround Saddam Hussein’s military-industrial nerve centers.

By now you know all about these walls and how they’ve been essentially used to carve up Baghdad into a strategic matrix of urban valves and neighborhood gates to seal off streets and alleyways from open markets and to control the overall flows and movements of insurgent attacks through out the city. The concrete slabs are everywhere in Iraq today, in Fallujah, Sadr City, and have easily become a scrolling urban faceplate for what almost seems now an interminable occupation by design in the Middle East.

Last time we mentioned Baghdad’s walls, U.S. and Iraqi forces were in the process of taking control of Baghdad with a major surge that the Washington Post wrote had triggered a run on concrete barriers, “which sometimes are not fully dry when military engineering units pick them up.” At one point one of the units was going through "as many as 2,000 barriers a week, installing two six-foot-tall, mile-and-a-quarter-long walls along the northern, western and southern borders of southern Ghazaliyah, while another unit blocked the cross streets on the east side with waist-high Jersey barriers."

These operations are so dangerous they are usually done as stealth missions late at night, “under cover of darkness” … while tanks and Humvees provide security for the cranes and forklifts operating for hours to erect new series of walls and gates, and structures that redirect the ingress and egress of traffic flows while designating a network of checkpoints.

It’s crazy to think that significant dimensions of a city, entire enclaves, massive pockets of urban neighborhood, could be completely spatially altered over night. It might be something akin to living in a dynamic metropolitan maze, or on some constantly shifting grid of architectural levers and spaces; to wake up one morning and find that a major causeway that has flowed in one direction for centuries has now been barricaded off, for some indeterminable amount of time, forcing generations of habitual traffic to flow now in completely new and counter intuitive directions; or, traffic flows that just discontinue altogether.

I couldn't imagine living in the chaos of a city whose identity was a neverending shift and tilt of formal and informal detours, alternative routes, dangerous short cuts, and de facto mergers of hectic traffic, parallel systems of transit mobility; life inside a city of roving walls; a forced kind of experimental city; a captive city; spontaneous reconfigurations; a transmorphing urbanism hostage to the context of war.

The biggest blast wall installation in Baghdad (perhaps besides the perimeter enclosing the Green Zone) appears to be a three-mile long stretch of concrete blocks, dirt piles, and coils of barbed wire surrounding the district of Azamiyah. In one report I’ve read “more than 3,000 individual sections of concrete blast walls throughout the city” since the major security crackdown a year ago went into effect. “These barriers included both Jersey barriers — short concrete dividers commonly seen on roadways in the United States — and larger 20-foot blast walls that commonly surround bases and living areas.”

I would be very curious to know exactly today just how many individual blast wall sections have been erected and now stand through out the city and all of Iraq. How many total miles of concrete barrier define the cartography of occupation? For that matter, how many miles of concrete blast wall line the urban borders of the rest of the world? How many tons of concrete stand in some political seam of contested territory internationally? How might we volumetrically estimate the weight and costs of the earth’s bordered geographies? How many billions of dollars stand tall in crude concrete blast walls?

In some ways it makes perfect architectural sense that a series of interconnected concrete barricades would become such a lucrative mechanism for the strong arms of globalization. They are the ultimate spatial product of war, like the junk product of the war machine itself.

The factory in Gopola allegedly produces 50 tons of concrete a day to fill U.S. military contracts. In general, the largest blast walls measure more than 18 feet high and weigh more than two tons, and take an entire day to manufacture. The factory also produces the shorter roadside barriers (or New Jersey barriers) that weigh around 470 pounds used mostly at checkpoints and along roads securing bases and other military installations.

Even though the surge has arguably improved some of the security conditions in Baghdad, the Bureau’s report says that the blast wall business has hardly slowed.

“The security improvement doesn’t affect too much the rate of production of blast walls. The American Army needs them and buys them nonstop to protect their military bases in Iraq.”

He added: “Of course I want the situation to get better. I am an engineer, I don’t want to make blast walls. I want to build things. We all want the situation to be better, and for this factory to close.”

Naomi Klein, in her own report, makes a great point about how the business of blast walls fits into the global economy, with little surprise to the utter neglect of Iraq, the country the occupation is supposedly serving in the first place.

With unemployment as high as 67 percent, the imported products and foreign workers flooding across the borders have become a source of tremendous resentment in Iraq and yet another open tap fueling the insurgency. And Iraqis don't have to look far for reminders of this injustice; it's on display in the most ubiquitous symbol of the occupation: the blast wall. The ten-foot-high slabs of reinforced concrete are everywhere in Iraq, separating the protected—the people in upscale hotels, luxury homes, military bases, and, of course, the Green Zone—from the unprotected and exposed. If that wasn't injury enough, all the blast walls are imported, from Kurdistan, Turkey, or even farther afield, this despite the fact that Iraq was once a major manufacturer of cement, and could easily be again. There are seventeen state-owned cement factories across the country, but most are idle or working at only half capacity. According to the Ministry of Industry, not one of these factories has received a single contract to help with the reconstruction, even though they could produce the walls and meet other needs for cement at a greatly reduced cost. The CPA pays up to $1,000 per imported blast wall; local manufacturers say they could make them for $100. Minister Tofiq says there is a simple reason why the Americans refuse to help get Iraq's cement factories running again: among those making the decisions, “no one believes in the public sector.”

11. Tofiq did say that several U.S. companies had expressed strong interest in buying the state-owned cement factories. This supports a widely held belief in Iraq that there is a deliberate strategy to neglect the state firms so that they can be sold more cheaply--a practice known as "starve then sell."

This kind of ideological blindness has turned Iraq's occupiers into prisoners of their own policies, hiding behind walls that, by their very existence, fuel the rage at the U.S. presence, thereby feeding the need for more walls. In Baghdad the concrete barriers have been given a popular nickname: Bremer Walls.

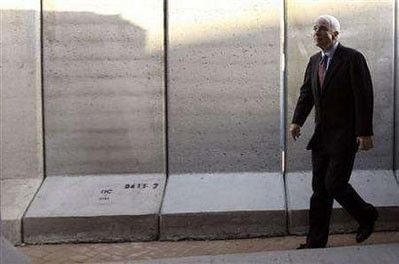

The Bremer Wall, real quick, was first fashioned by the Israelis as they began to put up their own monstrously divisive security barrier in the territories of the West Bank. As one source describes them,

“the Iraq version of these segmented walls is constructed out of thousands of portable, 12-foot-high slabs of steel-reinforced concrete. When stood upright on their pedestals, these "T-walls" look something like giant tombstones, totems perhaps from some long-lost Easter Island culture gone minimalist. When placed together edge-to-edge as "blast walls", they form the gray undulations that have now become Baghdad's most distinguishing feature. And because they proliferated during the administration of former US proconsul, L Paul Bremer, they became known to some as "Bremer walls".Klein’s comments are clearly supported by this statement by Andrew Butters for the Daily Star:

One popular rumor is that the Americans have been paying up to $1,000 for each of the three-meter high walls, named after the top US overseer here.

But the boom in Bremer walls hasn’t been good news for Iraqi manufacturers of concrete and cement. There is little if any Iraqi cement in a Bremer wall, and many of the concrete companies that supply the walls are either foreign or from Kurdish Northern Iraq.

Foreign and Kurdish firms got the jump on the wall contracts after the war because the US-led temporary government, the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA), needed the walls in a rush and Iraqi industry south of the Kurdish controlled regions, including all three Iraqi state-owned cement companies, was at a standstill.

The actual price paid for a Bremer wall is an elusive figure. But the rushed nature of the contracts and the continued risk of fulfiling them would justify a high price tag, according to international construction experts in Iraq.

Needless to say, as there is big business in manufacturing these walls there is just as big money in moving them. Barry Newhouse last year wrote about the "77 Group", a company in Irbil in the North of Iraq. Much of the company’s strategy has been invested in Turkish concrete and in blast wall delivery, earning them the title of the ‘blast wall haulers.’ Exceptionally big profits have come for this company as a result of the war. Group Executive Hersh Al-Tayyar explained saying “the company's net worth has grown from about $400,000 in 2003, to $300 million today, and over the years “has been awarded $1 billion in U.S. military contracts.” But, it is also, like everything else in Iraq, exceptionally dangerous.

As of 2007, 32 employees had been killed since the beginning of the war “despite armed guards and heavy machine guns on pickup trucks that travel with the convoys.” Guards earn between $1,000 to $2,000 a month, easily quadruple the average salary in Iraqi Kurdistan. According to the same article, “The 77 Group says it pays death benefits to employees killed on the job.” Though in practice this has been disputed by some driver families.

The company’s sentiment is that they are not only helping the Americans, but “These concrete walls will stay here for the Iraqi people after the Americans leave.” […] “The Iraqi people will need them.”

A sad final reflection to end on - that these barriers will persist long after the occupation has ended, whenever that may be. But for as something designed to be so temporary, the fact that their permanence has become the most defining quality of the blast wall is a tragic commentary on the legacy of occupation, to say the least. As if occupation (implicitly temporary) is also now somehow inherently permanent too; as if the urban scars left behind could never be forgotten. Are these the structures of a temporary or permanent occupation? Or are these the concrete spaces of something indefinitely in between states of temporary and permanent? Are these the symbolic structures of geopolitical limbomania, architecture in the balance of perpetual war?

In one of these articles I’ve cited here the blast walls are described as a lineage of towering tombstones that link across the city, a great analogy actually for both a post-Saddam landscape as well as what has been made of it by the American occupation and the war on terror - cities reduced to blast wall cemeteries. The blast wall as the liminal architecture of Iraq's historical transition; as the fragmented sarcophagus of Iraq's violent past.

Of course, no concrete barrier claimed to be a temporary measure could seem more permanent right now than the Israeli Security barrier, described by General Amos Yaron, the Director General of the Israeli Minister of Defense, as “a project from an engineering perspective” that “is the greatest Israel has ever known.” In an interview he gave in Simone Bitton’s documentary film Mur he said “each day more than 500 pieces of heavy machinery move and transport millions of cubic meter of earth” to construct the Security barrier in the West Bank. “Each kilometer of barricade costs around 10 million shekels, or roughly $2 million dollars.”

In other words, he says, “if the project is 500 kilometers long its total cost will be around 5 billion shekels.”

The actual cost of the Israeli barrier has been highly disputed in the media. This link seems to do a good job of tracking what has been reported in the media, what has been corrected in the media, and finally what seems to be the most accurate cost of the Israeli wall, which in total possibly could reach 429 miles roughly and upwards of $ 3 billion dollars depending upon the eastern span.

Another dimension to all of this business about concrete however were the reports that came out about Palestinian profiteers selling concrete to the Israeli government that was originally sold to the Palestinians by Egypt at below market prices strictly to build homes. The Telegraph stated,

Cheap cement to help rebuild Palestinian communities devastated by war with Israel has been resold at huge profits for use in Israel's controversial West Bank security wall and settlements in the occupied territories, Palestinian legislators say.

Palestinian Authority officials have assisted in the scheme, allowing the businessmen to make millions of dollars and depriving the Palestinian Government of taxes, according to an investigation by Palestinian lawmakers.

The businessmen, using permits given to them by a high-ranking member of Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat's cabinet, sold thousands of tonnes of the cement to Israeli contractors at a 50 per cent profit. The cement had been sold to the Palestinians by Egypt at below-market prices.

As well as aiding the Israeli projects and producing up to $US5.5 million ($A7.9 million) in profits for the middlemen, the cement deals cost the Palestinian public treasury as much as $US1.6 million in uncollected taxes, according to the investigators. It is unclear whether the practice is continuing.

The report reveals that the cement originally came from Egyptian companies which supplied it at a huge discount of $22 (£12.50) a ton to help rebuild dilapidated Palestinian houses or buildings bulldozed by the Israelis.

Between September 2003 and March this year, 420,000 tons of cement were allegedly sent to three big Palestinian companies. According to the report, however, only 33,000 tons were sold in the Palestinian market. The vast bulk was transported to Israel on trucks owned by the three firms. According to Mr Khreishe, the cement was then sold with a mark-up of at least $15 a ton - and possibly as high as $100 - making profits of well over $6 million (£3.4 million) for company executives.

Anyway, sorry for all of the bulk quoting and lengthy extracting from these articles, but that is about as much as I have been able to track down with regards to the value of concrete in the business of blast walls.

But I would be curious to know how the blast wall market has effected the global cement market; where blast walls are primarily produced, and to what other off-the-radar countries they are being exported to as well. And, with speculative curiosity, would love to try and determine how many miles of blast wall have been expanded through out Iraq, the Middle East, the world! And how much does all that weigh? So, for instance, we could say, the occupation of Iraq actually has a physical weight to it, equivalent to its symbolic legacy. If the blast wall is the penultimate symbol right now of the occupation, how much does the occupation weigh on Iraq? Can wars be measured this way, in terms of their physical mass, their actual costs in gravity? How much do wars weigh? The Cold War, with its unparalleled network of bunkers, surely would weigh the most in terms of concrete.

Yeah, it's a silly comparison, I know. But think about how much money has been spent on blast walls alone. And suppose the occupation ends one day, how long will those walls really remain in place, what forlorn legacy is being cemented in the streets of Baghdad today for generations to come? If they were removed at some point, I wonder what would happen to all that concrete? Would it get formally recycled, or broken down into lucrative scrapper markets underground? In such a market, I wonder how much concrete it would take to sustain the life of an average refugee family in Iraq for a month. Who would even own the blast walls if the occupation were to suddenly cease? Would the Americans leave but then come back to reclaim their heaping piles of blast walls one day? Or, could we imagine in a bizarre post-colonial kind of way some newly adaptive reuse project for all these oppressive slabs, say, Bremer Wall refugee rehousing projects? Or is that just too symbolically grim to even consider? How about future bridges and infrastructure made out of old blast walls? Think of all the Iraqi reconstruction projects that aren't getting the attention they deserve compared to the constant fabrication of these barriers.

I don't know, I guess it just begs a later question: are these barriers useful for any thing else in their current form? Like, for example, if we were to gather them all up, what would they -- what could they -- possibly amount to?

Forgive this utterly superfluous train of thought, I suppose I'm just trying to revision them somehow, since they have already become such an urban staple in certain parts of the world. Could they in the end be used for some post-war reconstructive means?

Anyway, if any of you readers out there can provide additional info at all regarding these things it would be much appreciated, as I am sure I have a very limited scope here as to the reality of their fabrication, and possibly even their current afterlives beyond war.

13 Comments:

Good post, thanks.

So...

Bad people set off lots of bombs.

But it appears this articles thesis is:

Blast walls that stop bombs = Bad.

...Having a hard time following the logic here.

Never knew you could write so much with such a level repetitiveness on Blast Walls.

Far too long winded, I lost all interest in reading any further after about half way - and I'm a journalist myself so I speak from experience and a position of knowledge.

Also, what's with all the rhetorical questions? Didn't they teach you in university that the posing of questions to your reader is a big no-no?

Nice pictures though, and fairly informative. Just wish the whole article wasn't so bloated and full of emotional rhetoric.

Thanks for the excellent post.

"I couldn't imagine living in the chaos of a city whose identity was a neverending shift and tilt of formal and informal detours, alternative routes, dangerous short cuts, and de facto mergers of hectic traffic . . . ."

I recall that the BQE would've fit this description on certain days . . . .

unerringly original aperture on the business of war. anonymous comments on non sequiturs arising from 'this articles thesis'(?). post from rich says 'too long winded'. go figure!

I say, this is the kind of discursive dialectic of the built up and built down environment that we need to hear and that is painfully, urgently relevant. Concrete is useful but has an enormous inherent entropy. takes a lot of energy to make it. most concrete is owned or distributed by cartels(this fact is all too well known in the developing world), most of them with distinctively american interests.

Blast wall sourcing and traffic flow alterations are the kind of mundane thing that don't hit the western media front page but bear upon the lives of the incarcerated and excluded. the article was very important and decidedly unpoliticised. israeli vs palestine, kurd vs shia vs sunni, and all that has thankfully and responsibly been left out of the dialogue for the rest of the inernet to flame it out for themselves.

more of the same please mr bldblog

Brian,

Great post. I am particularly interested in the following two ideas. First that the physicality of the "occupation" can be measured in mileage and tonnage, as represented by the blast walls found all over the country.

And that much of this construction/erection takes place overnight, when the country is sleeping. They then wake up to find the city's organizational structures changed and altered...

Very informative....I found a lot of information and ideas here that will help my own studies of walls. Keep up the great posts.

I like to ask a question on regarding the recent build of blast walls being erected in Sadr City. Who provide the concretes, who make them, and who do the deployment of the finished product surrounding the inhabitants from the Bagdad area?

I am having trouble finding out these questions.

Gopala is

35 degress 38'43.07" N

45 degrees 02'06.86 E

in Google Earth...

anyone able to find the cement factory?

Oh my god, the horrible injustice of an Iraqi child sheltered from a car bomb by a blast wall! Doesn't that child know walls are ugly? That the big concrete syndicates profited by saving her life? I can only hope someday we tear down the Great Wall of China so that we can inspire the people of Iraq to rid themselves of their own historical reminder of the realities of war. Also, it's pretty clear after reading this article that George Bush must have invaded Iraq to help his buddies in the concrete business. Saddam Hussein never would have stood for this! He did not care for artificial barriers that divided peoples. Like the Iraq-Iran border. Or the Iraq-Kuwait border. It was the Bush family and their yee-haw cowboy attitude that tries to keep people inside boundaries.

Paul Virilio had some interesting ideas about bunkers and concrete. check out Bunker Archeology.https://historyofourworld.wordpress.com/2010/02/15/bunker-archeology-paul-virilio/

"So...

Bad people set off lots of bombs.

But it appears this articles thesis is:

Blast walls that stop bombs = Bad.

...Having a hard time following the logic here."

No logic, sentiment.

A bomb is can be an 'ephemeral' sort of thing. In good times they don't happen at all.

A blast wall on the other hand, could be forever, or the half-life of ferro-concrete whicever comes first. It's an ugly 'eyewitness' to failure.

Post a Comment

<< Home