Re-urbanizing the Homeless

Recent obsessions with the border have made me neglect so many other layers of what I think make up the composite of a Subtopian landscape. One of which is homelessness - global urban homelessness. In fact, it was my early concern with the homeless issue here in San Francisco that got me to rethink my interests in architecture again a few years ago, searching to relate social policy and spatial practice through a type of architectural activism.

From there, my fascination with the political domains of architecture grew, as well as my need to learn more about the spatial dimensions of politics. Two sides of the same coin, perhaps. Via the prison issue and my own experiences wandering around India’s squatter societies, all these layers sort of took off and fused together in the exploration of military landscapes and looking more closely at the disciplinarian nature of institutions and state power. About a year and a half ago Subtopia, and the search to define ‘military urbanism’, was born.

Be that as it may, I came across this project not too long ago, which again takes a temporary approach that in the end I think might not really help resolve the crisis of housing the homeless at all. While it cleverly addresses the needs of persons who might choose to remain in the streets, or of some global nomads where shelter is simply unavailable, the main problem I have with these types of solutions is that they don’t challenge the political structure of municipal housing markets to provide the necessary supply of supportive, transitional, or affordable housing that is really required to get people off the streets in cities.

Of course, I understand solutions are needed for an interim period where cities may have no viable means of housing or sheltering their homeless people at the time. But, I would still like to see more innovation in the ways architectural solutions can write themselves into other existing places that may be overlooked in the city, or to chart new ways that design can re-write the housing code in some way, or alter construction methodologies, recycle urban scraps, perhaps approach adaptive reuse or historic preservation in a unique and revolutionary manner. But I will speak more about that in a moment.

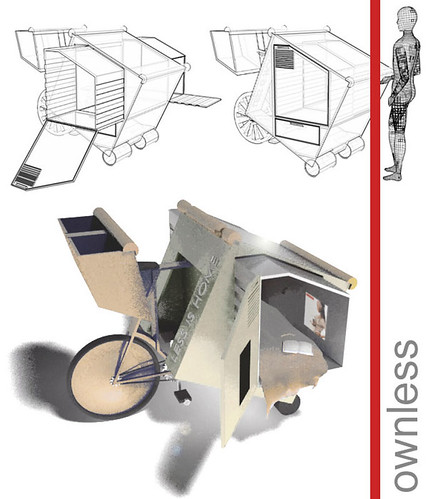

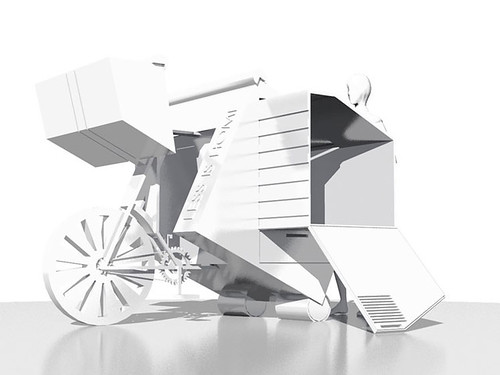

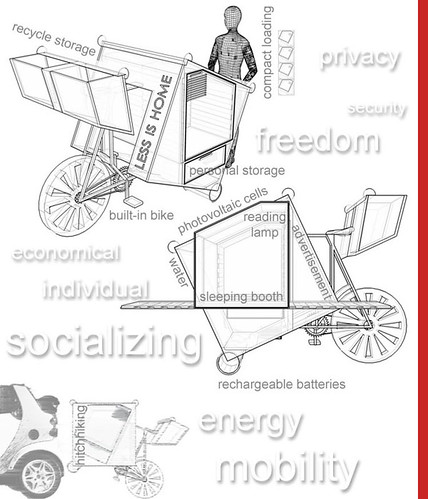

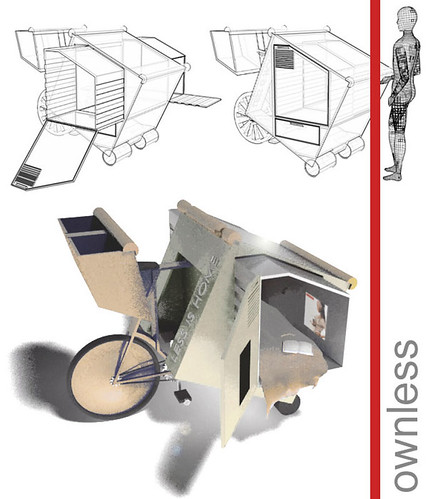

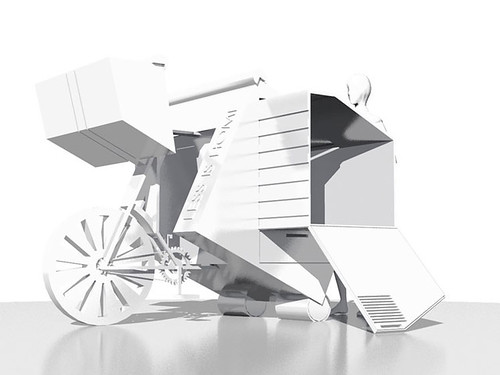

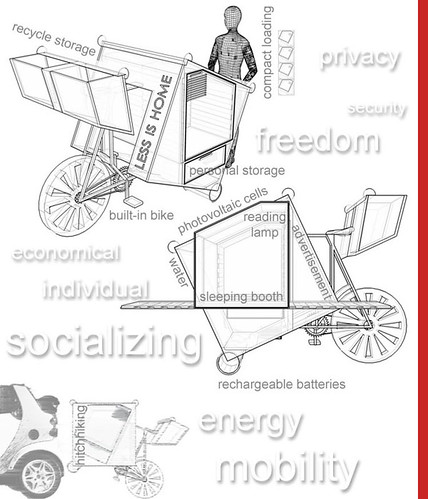

The Ownless unit, as it is called, however, when we read the philosophical statement that describes it, seems more like a space for a sadhu rather than the victim of homelessness or a forcibly displaced person deprived of access to a home. [For those who don’t know, a sadhu is a holy man in India who has wittingly given up all of his worldly possessions in order to wander the country in search of enlightenment, or spiritual fulfillment.] And while I can relate to that (as I spent many months wandering the planet in my own sort of quest for enlightenment – I am even writing a book of travel narratives on the topic of an urban sadhu), I still find this proposal a bit philosophically cutesy and pseudo-utopic.

Geotectura, the Israeli firm who designed the compact housing vehicle, implies this is a solution for the urban environment, and builds upon the psychological notion that a person can positively start from scratch in life, with nothing, and therefore exist in this space with a certain political environmental conscientiousness in mind. The two designers, Joseph Cory and Jacob Eichbaum say:

Granted, the design is pretty cool. It has a pull out bed, special outer advertisement space for potentially making money, adequate storage space, lamps and lights, a hitch that allows it to be pulled by other vehicles; it allegedly provides security (though I wonder how these mobile cubicles on the street all the time can really be expected to be secure); the rooftop is lined with photovoltaic cells that charge batteries so it is not only pedal-driven but can move as a non-polluting vehicle, as well. It’s nifty, to be sure! But I am not sure that homeless people need nifty. Or to be urged to just zen-out and accept the minimalist essence of their homeless existence as a base spiritual clarity, or state-of-mind, I don't know - it gets a little wacky for my blood.

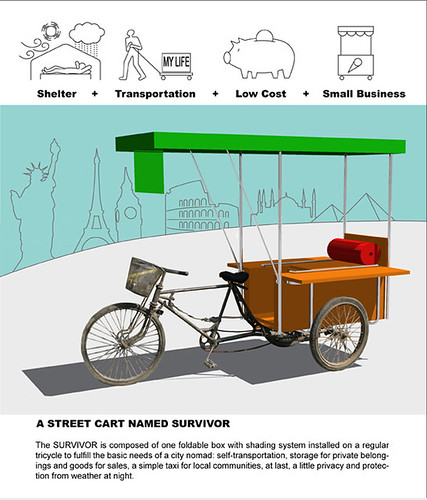

A few months ago Design Boom organized the shelter in a cart design competition. There were some very cool ideas and projects, don’t get me wrong. It’s a seductive context: nomadic urbanism. Especially when we think about all of the millions of people on the move around the planet right now, which is perhaps where I see these types of homeless coaches being more useful. Maybe in Darfur, or India, or along migration zones through out Africa. But I still have trouble trusting their efficacy in a truly urban environment like San Francisco or New York City.

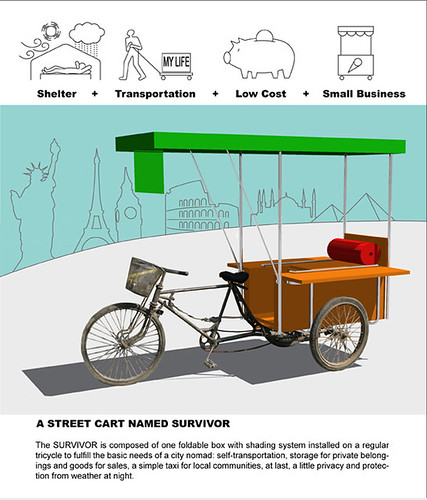

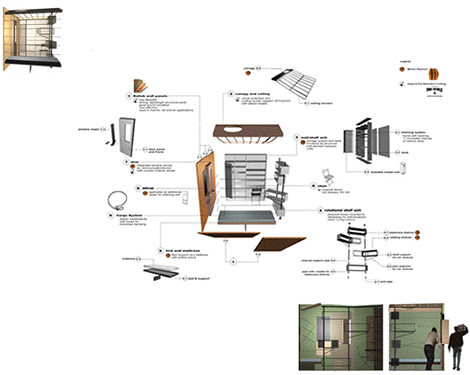

[Image: the street cart named survivor, design by : ing-tse chen from china.]

Cameron Sinclair chose one design from the competition as particularly noteworthy, but said this as a general reflection:

While I agree with him, is this really the strategy for addressing any part of the urban homeless issue? Not really. His questions towards the end get at the crux a bit more, but I think they need to be re-aimed and more specified? Of course designers have a role in solving homelessness, and yes I believe homelessness can be solved. But what specifically does the designer have to consider? Band-aid solutions like shelter-carts are too easy for architects, too detached I think, as much as they seek to engage the problem.

How can the designer force municipalities to re-calibrate their strategies for providing more efficient affordable housing? What types of innovative programs can designers instigate to provide both housing and jobs in a single planning scheme? How can designers force local government officials and planning departments to take advantage of already pre-existing wasted space? Unremdiated space? How can designers partner with non-profs more infrastructurally and determine new funding mechanisms in partnerships with the city to fund these types of projects regularly? The solution itself has to forge a new municipal housing model for all of these actors to come together and work politically.

With all of these groovy sidewalk shelter designs and homeless chariots on the drawing board, I still think the First Step Housing design competition back a few years ago was on a more pointed and realistic trajectory with all of this. Real quick, the goal was to remake an existing flophouse in New York City’s run down Bowery neighborhood and propose ways of converting and re-using the building for housing the homeless. One of the winners was a project by New York City-based firm Lifeform, who I invited to join us at Postopolis! to discuss their project.

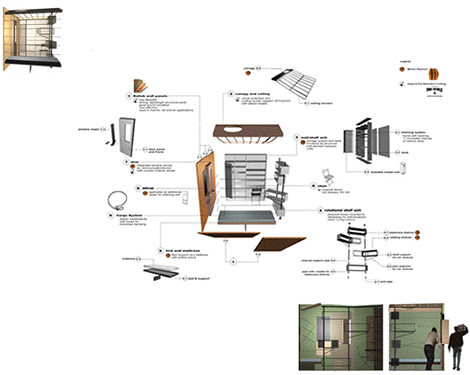

You can read coverage of Monica Hernandez’s presentation at City of Sound, but in essence they had proposed a very modular and flexible kit of parts system for a floor in the building with three different types of living spaces that could be configured to more specific needs and unique personalities. Look at the design right here. Read more here. It became symbolic as a way attention to the homeless population could also help remake the building, even the neighborhood in some way. That to me seems like a much more progressive mode of using design to address urban homelessness, to address the broader context, to revitalize some part of the city.

In San Francisco, a couple of years ago housing rights activists helped pass the Surplus Property Ordinance, which effectively secured several city-owned sites and parcels of land that have sat vacant, unused, or simply unconsidered in terms of any real development, for the sole purpose of building housing for the homeless. I was involved with this for awhile, but sadly have fallen a bit out of the loop. But, even more disappointing is that I don’t think much real housing has come out of this yet, though there have been some tangible results. But the ordinance is a great one. It forces different departments like Park and Rec. & the Fire Dept. to periodically transfer some of their underutilized parcels, and even some odd slivers of seemingly uninhabitable real estate dispersed through out the city, to the Mayor’s Office of Housing. Some of the sites are vacant office buildings that have been used merely as storage for bureaucracies for years, or that have been kept in holding simply because certain departments didn’t want to give up entitlements to their real estate even though they have not been able to put it to any solid use in ages. Here is a chance for architects to partner with non-prof developers and try to work with these conditions; odd lots, nook and cranny spaces around town, separate floors in old office towers, sloped and narrow park space, etc. Authoring productive space into the dead fabric of the city - recontextualizing dead space.

Like everything else in San Francisco, particularly housing development, and even more particularly homelessness, progress is always impeded by contentious politics. In this case, the allocation of money in the city’s affordable housing kitty and to which developers those funds will go, into which neighborhoods, and for which specific projects, all play into the unfortunate political factional divide that gets in the way of getting actual housing built. Of course, NIMBYism is always a factor, too (especially in SF), and when it comes time to proposing a homeless supportive housing project in certain neighborhoods, well - that always opens another can of worms.

Nevertheless, I keep thinking of strategies of adaptive reuse as a means for architects to write themselves into the solution around housing the homeless. I think of successful design initiatives like the Accessory Dwelling Units (ACUs, or Granny Flats), which have also forced a re-examination of building codes to allow micro-units into existing housing fabrics and neighborhood densities.

[Image: Rainbow Apartments and the New Carver Apartments and run by the nonprofit Skid Row Housing Trust, Michael Maltzan Architecture. Photo via NYT.]

And the more I think about the erosion of social welfare in the United States, the decline in the institutions of health care and education, the gap and inaccessibility that is increasing for the middle and lower class populations of this country who are looking at a dire future of basic needs deprivation, the more I see models like supportive housing serving greater purposes than just housing the homeless. [For those who aren’t familiar with supportive housing, it is housing specifically designed for homeless people that includes certain health care, vocational, educational, services provided on–site, programmed into the design of the building. Considered the only viable solution to really tackling the chronically homeless, it has proven incredibly successful. Read this book review I wrote awhile back on the subject.]

What if a melding of supportive housing, co-housing, transitional, elderly and low-inc family housing, became the ideal model for affordable housing in general across the country? And an optimal urban building recycling practice as well? Whereas the state continues to let people down by not providing adequate institutional provisions like public health care and education, and by letting affordable housing stocks dwindle, perhaps the new green urban housing model of the future will account for this by programming these necessities on-site, building upon new models of community and alliances with local non-profits who begin to pick up the slack?

We become this bad-ass tribe of bottom-feeding city-scraping architects and builders, filling in the cracks, helping the homeless to house themselves.

Who knows, maybe in planning for specific housing models and solutions for the homeless we stumble upon solutions for a greater housing and social welfare crisis looming at large?

From there, my fascination with the political domains of architecture grew, as well as my need to learn more about the spatial dimensions of politics. Two sides of the same coin, perhaps. Via the prison issue and my own experiences wandering around India’s squatter societies, all these layers sort of took off and fused together in the exploration of military landscapes and looking more closely at the disciplinarian nature of institutions and state power. About a year and a half ago Subtopia, and the search to define ‘military urbanism’, was born.

Be that as it may, I came across this project not too long ago, which again takes a temporary approach that in the end I think might not really help resolve the crisis of housing the homeless at all. While it cleverly addresses the needs of persons who might choose to remain in the streets, or of some global nomads where shelter is simply unavailable, the main problem I have with these types of solutions is that they don’t challenge the political structure of municipal housing markets to provide the necessary supply of supportive, transitional, or affordable housing that is really required to get people off the streets in cities.

Of course, I understand solutions are needed for an interim period where cities may have no viable means of housing or sheltering their homeless people at the time. But, I would still like to see more innovation in the ways architectural solutions can write themselves into other existing places that may be overlooked in the city, or to chart new ways that design can re-write the housing code in some way, or alter construction methodologies, recycle urban scraps, perhaps approach adaptive reuse or historic preservation in a unique and revolutionary manner. But I will speak more about that in a moment.

The Ownless unit, as it is called, however, when we read the philosophical statement that describes it, seems more like a space for a sadhu rather than the victim of homelessness or a forcibly displaced person deprived of access to a home. [For those who don’t know, a sadhu is a holy man in India who has wittingly given up all of his worldly possessions in order to wander the country in search of enlightenment, or spiritual fulfillment.] And while I can relate to that (as I spent many months wandering the planet in my own sort of quest for enlightenment – I am even writing a book of travel narratives on the topic of an urban sadhu), I still find this proposal a bit philosophically cutesy and pseudo-utopic.

Geotectura, the Israeli firm who designed the compact housing vehicle, implies this is a solution for the urban environment, and builds upon the psychological notion that a person can positively start from scratch in life, with nothing, and therefore exist in this space with a certain political environmental conscientiousness in mind. The two designers, Joseph Cory and Jacob Eichbaum say:

The Ownless unit is transforming the homeless terminology into a hopeful term. On the same tone of the modernist sentence: less is more the Ownless unit is declaring that less is home. And indeed - why not consume less if we can maintain the basic needs and freedom of mankind. Ownless unit is first and foremost a psychological state of mind saying that being in this situation is not the end of the world but rather adjusting with optimistic approach to a new situation. You can restart from nothing and build yourself again by hanging onto the important values and letting go the wasteful style of living.

Granted, the design is pretty cool. It has a pull out bed, special outer advertisement space for potentially making money, adequate storage space, lamps and lights, a hitch that allows it to be pulled by other vehicles; it allegedly provides security (though I wonder how these mobile cubicles on the street all the time can really be expected to be secure); the rooftop is lined with photovoltaic cells that charge batteries so it is not only pedal-driven but can move as a non-polluting vehicle, as well. It’s nifty, to be sure! But I am not sure that homeless people need nifty. Or to be urged to just zen-out and accept the minimalist essence of their homeless existence as a base spiritual clarity, or state-of-mind, I don't know - it gets a little wacky for my blood.

A few months ago Design Boom organized the shelter in a cart design competition. There were some very cool ideas and projects, don’t get me wrong. It’s a seductive context: nomadic urbanism. Especially when we think about all of the millions of people on the move around the planet right now, which is perhaps where I see these types of homeless coaches being more useful. Maybe in Darfur, or India, or along migration zones through out Africa. But I still have trouble trusting their efficacy in a truly urban environment like San Francisco or New York City.

[Image: the street cart named survivor, design by : ing-tse chen from china.]

Cameron Sinclair chose one design from the competition as particularly noteworthy, but said this as a general reflection:

“The brief set out was fairly controversial given the fact that the criteria was to develop a ‘cart’ system to support those who chose to stay on the streets, rather than the housing shelter approach. During the review the one thing that worried me was that many entries ignored two basic needs – protection of ones valuables and a self-sustaining economic engine.”

“The competition and these initiatives are not the answer to issues of homelessness but they force the design community to begin to ask serious questions. What is the role of the designer? Who is the designer? Should we support these communities? Is homelessness a solvable issue?”

While I agree with him, is this really the strategy for addressing any part of the urban homeless issue? Not really. His questions towards the end get at the crux a bit more, but I think they need to be re-aimed and more specified? Of course designers have a role in solving homelessness, and yes I believe homelessness can be solved. But what specifically does the designer have to consider? Band-aid solutions like shelter-carts are too easy for architects, too detached I think, as much as they seek to engage the problem.

How can the designer force municipalities to re-calibrate their strategies for providing more efficient affordable housing? What types of innovative programs can designers instigate to provide both housing and jobs in a single planning scheme? How can designers force local government officials and planning departments to take advantage of already pre-existing wasted space? Unremdiated space? How can designers partner with non-profs more infrastructurally and determine new funding mechanisms in partnerships with the city to fund these types of projects regularly? The solution itself has to forge a new municipal housing model for all of these actors to come together and work politically.

With all of these groovy sidewalk shelter designs and homeless chariots on the drawing board, I still think the First Step Housing design competition back a few years ago was on a more pointed and realistic trajectory with all of this. Real quick, the goal was to remake an existing flophouse in New York City’s run down Bowery neighborhood and propose ways of converting and re-using the building for housing the homeless. One of the winners was a project by New York City-based firm Lifeform, who I invited to join us at Postopolis! to discuss their project.

You can read coverage of Monica Hernandez’s presentation at City of Sound, but in essence they had proposed a very modular and flexible kit of parts system for a floor in the building with three different types of living spaces that could be configured to more specific needs and unique personalities. Look at the design right here. Read more here. It became symbolic as a way attention to the homeless population could also help remake the building, even the neighborhood in some way. That to me seems like a much more progressive mode of using design to address urban homelessness, to address the broader context, to revitalize some part of the city.

In San Francisco, a couple of years ago housing rights activists helped pass the Surplus Property Ordinance, which effectively secured several city-owned sites and parcels of land that have sat vacant, unused, or simply unconsidered in terms of any real development, for the sole purpose of building housing for the homeless. I was involved with this for awhile, but sadly have fallen a bit out of the loop. But, even more disappointing is that I don’t think much real housing has come out of this yet, though there have been some tangible results. But the ordinance is a great one. It forces different departments like Park and Rec. & the Fire Dept. to periodically transfer some of their underutilized parcels, and even some odd slivers of seemingly uninhabitable real estate dispersed through out the city, to the Mayor’s Office of Housing. Some of the sites are vacant office buildings that have been used merely as storage for bureaucracies for years, or that have been kept in holding simply because certain departments didn’t want to give up entitlements to their real estate even though they have not been able to put it to any solid use in ages. Here is a chance for architects to partner with non-prof developers and try to work with these conditions; odd lots, nook and cranny spaces around town, separate floors in old office towers, sloped and narrow park space, etc. Authoring productive space into the dead fabric of the city - recontextualizing dead space.

Like everything else in San Francisco, particularly housing development, and even more particularly homelessness, progress is always impeded by contentious politics. In this case, the allocation of money in the city’s affordable housing kitty and to which developers those funds will go, into which neighborhoods, and for which specific projects, all play into the unfortunate political factional divide that gets in the way of getting actual housing built. Of course, NIMBYism is always a factor, too (especially in SF), and when it comes time to proposing a homeless supportive housing project in certain neighborhoods, well - that always opens another can of worms.

Nevertheless, I keep thinking of strategies of adaptive reuse as a means for architects to write themselves into the solution around housing the homeless. I think of successful design initiatives like the Accessory Dwelling Units (ACUs, or Granny Flats), which have also forced a re-examination of building codes to allow micro-units into existing housing fabrics and neighborhood densities.

[Image: Rainbow Apartments and the New Carver Apartments and run by the nonprofit Skid Row Housing Trust, Michael Maltzan Architecture. Photo via NYT.]

And the more I think about the erosion of social welfare in the United States, the decline in the institutions of health care and education, the gap and inaccessibility that is increasing for the middle and lower class populations of this country who are looking at a dire future of basic needs deprivation, the more I see models like supportive housing serving greater purposes than just housing the homeless. [For those who aren’t familiar with supportive housing, it is housing specifically designed for homeless people that includes certain health care, vocational, educational, services provided on–site, programmed into the design of the building. Considered the only viable solution to really tackling the chronically homeless, it has proven incredibly successful. Read this book review I wrote awhile back on the subject.]

What if a melding of supportive housing, co-housing, transitional, elderly and low-inc family housing, became the ideal model for affordable housing in general across the country? And an optimal urban building recycling practice as well? Whereas the state continues to let people down by not providing adequate institutional provisions like public health care and education, and by letting affordable housing stocks dwindle, perhaps the new green urban housing model of the future will account for this by programming these necessities on-site, building upon new models of community and alliances with local non-profits who begin to pick up the slack?

We become this bad-ass tribe of bottom-feeding city-scraping architects and builders, filling in the cracks, helping the homeless to house themselves.

Who knows, maybe in planning for specific housing models and solutions for the homeless we stumble upon solutions for a greater housing and social welfare crisis looming at large?

7 Comments:

Hey Bryan ! great article -

hopeful and critical as all your witting is. I like to think we can still attach certain virtues to the idea of homelessness.

I keep wandering why there is this gap between that and what makes us create solutions for these problems as designers.

Thanks Monica!

I appreciate that comment. It certainly is a tricky issue, partly because of a lack of both political and architectural will, I think - and yes, that endless stigma of the homeless to begin with.

I don't know - I wish more designers were invested in considering collaborating on solutions that might only minimally involve architecture, but rather get architects more into the political fold of activism and policy advocacy.

Perhaps that is where more of the fight needs to be, and if architects had a voice there, politicians might be willing to experiment more with the kinds of design solutions architects ultimately have to offer.

If architects would start being seductive again, instead of reactive like it is now, maybe then it would be more realistic to win the "powerful", i.e. individuals in politics and economy, for more "experimental" ideas. Designing objects is delicious, and of course we designers enjoy it, but there is much more to it when it comes to implementation.

To convince those who make implementations possible is maybe the core task. But I don't believe this can be achieved purely by developing design proposals. Let's be honest, nearly every designer could come up with nice design solutions for the same problem. Perhaps the designs would even be very similar since confined to very basic needs. And some of existing design examples resemble objects that have already been created on the streets - especially when thinking of India or Afghanistan, people very often create make-shift solutions of mixed use objects for work, sleep, mobility. They aren't helpless - I still believe they're the best designers for their own situation. What really makes the difference regarding trained designers is the process around it. Commercial plans, implementation strategies, economic connections (something I like to call efficient friendships), political support (related to publicity), and communal acceptance (participation).

niloufar,

i agree and i think that was expressed in my post, as well.

not everything can be solved through design alone, but i think that is a difficult thing for designers to accept - that maybe their nifty brilliant solutions will not have any impact on the problem at all, in fact they may only enforce the conditions which have led to the problem in the first place, inadvertently of course.

significant change requires vast cooperation between various entities, and architects need to step out of their foxholes and go out and shake some hands and get their voices more into the debates around policy, funding mechanisms, and social rights advocacy. they need to don a political conscience !

it's not enough to just lob out a new cool container, that's not what is needed all of the time. change requires multiple voices from different angles chipping away at the same political walls. in that sense it is as much about deconstruction as new construction itself.

Bryan -

I agree with you in that architects/designers/etc. need to get involved at a much broader level in order to begin "solving" the problems of homelessness, if there even is such a solution. Design is more appropriate for the "one small difference" type of approach. I don't think that is bad, but I think the small solutions extend from humanitarian efforts and realizing the small connects we share with people who are homeless. There are probably plenty of people out there who would appreciate the little cart, but to submit it as a "global" solution fails to address the problem, and shows the "top-down" mentality that architects tend to have. I'm personally not a fan of modular and mass-production, so somewhere in my mind I really don't believe architectural solutions on a massive scale will solve anything. Too many variables involved, as you said, with politics and social policy.

kristin,

absolutely. if we think of every actual physical space designers create as having a corresponding political space as well, occupying a virtual sphere of influence in our social system, so that we begin to think of an overarching political architecture implicit in the actual spaces of architecture themselves, then perhaps architects can begin to see the usefulness of their vantage as being able to significantly influence politics as well. Many architects don't believe they should get involved with politics, but i just see that as leading to apathy and complicitness.

i would like to see architects thinking about the political ramifications of their work and choose more work on that basis; (not as developers just looking to push their own deals) but as a form of political responsibility. how can their design projects construct a space of political agency to negotiate change through policy advocacy and social action? how can their projects invite a new sphere of political space? etc.

Thanks Bryan, I enjoyed this article as well.

I find myself in the same dilemma of designing portable homeless shelters such as the 'Ownless', and thinking that this 'band-aid' solution merely masks the need for governments to finance the creation of long-term supportive housing.

Post a Comment

<< Home