The City in the Crosshairs: A Conversation with Stephen Graham (pt. 2)

Alas, here is the second part of my interview with Stephen Graham who teaches Human Geography at the University of Durham and is the Deputy Director of the Centre for the Study of Cities and Regions and the Associate Director of the International Boundaries Research Unit.

In Part 1 we talked about the nature of cities as sites constituted by what Steve calls the “new” military urbanism, a state that is less about the border than its internalization, less about linear lines of defense than amorphous biometric security nets, less fortress than more interwoven surveillance technologies that re-inscribe political violence into the city through a mixing of privatization, miltarism and corporatism. In Part 2, we discuss how the city is produced by imaginary geographies that emerge in culture to help re-image foreign places as sites of "necessary" imperial conflict and the role of infrastructure during war time, particularly that of state-backed disruption. Steve also gives us a gander at what he thinks the future of geopolitical conflict will look like as new “contesting transnational architectures of imperial urbanism” mount up around strategic geographies of global resource accumulation.

[Bryan Finoki] What role does the urban geography of the Middle East have in fomenting social change, democratic uprising, theocratic fortitude, fascist dictatorship, or, in just helping to author a good old-fashioned run-on narrative of perpetual conflict? What skeletal imprints of ancient empire-building are evident in the modern transformation of these cities today? How are contemporary Arab cities becoming the future fossils of an 'empire urbanism'? Or, are they, perhaps, becoming the places of empire’s own self-destruction? What are places like Fallujah, Najaf, Baghdad, Jerusalem, being turned into and what might they represent 150 years from now?

[Stephen Graham] I think the legacies of western colonial empires are much more important than the legacies of classical or Mesopotamian civilizations. Many of the problems of the Middle East are the result of casual line-drawing around colonial zones of occupation and exploitation which transmogrified into nation states riven with overwhelming internal contradictions, which could really only ever be maintained through repression and political violence. Iraq is a classic example here.

Certainly, the extravagant project of a neoconservative “New American century”, based on continuous expeditionary and urban warfare, seems mortally wounded after Iraq. But this doesn't mean that U.S. and western imperialism will cease or wither. The Caspian Basin oil reserves are the biggest geopolitical prize of the early 21st century. With ‘peak oil’ this prize will only grow. So, the struggle between U.S., Russian and other interests to control geopolitics of oil in the Middle East will only intensify.

The key here will be the age-old colonial tactic of establishing and maintaining corrupt, client regimes and proxy armies rather than full-scale invasion and occupation. In the case of the U.S., this is likely to be backed up by large-scale private military corporations, supported by a small, elite military presence relying on high-tech surveillance and targeting within what the Pentagon is calling the ‘long war.” I’m skeptical that a U.S. president will commit a full-scale force to a Middle Eastern invasion in the near future after Iraq.

[Bryan Finoki] Not that the state’s failure to succeed in Iraq is any part of the plan, but it does help to more quietly institutionalize the privatized war market and to pacify the public who will become less invested in the troops over time and also further removed from being able to scrutinize the conflict as a “private war.” So, are we saying that the Long War will ultimately drive future conflict zones around key geopolitical sites further underground into state-sanctioned clandestinization? Are we entering a new era of secret wars?

[Stephen Graham] Yes, I think so. When war becomes a purely corporate activity, the monopoly of violence long seen as a characteristic of modern western states withers away. Instead, the US state military, in particular, increasingly shepherd a vast array of private military, security and ‘reconstruction’ corporations – as well as proxy armies. These are utterly unregulated and unscrutinised and able to perpetuate civilian atrocities and absorb their own casualties almost invisibly whilst the western media continues to fetishise about dreams of ‘clean’ war through new technology.

[Bryan Finoki] Cities also serve a different role in conflict, one that is indirect and depicted rather than physically conquered. How would you summarize the role cities play in helping the west to project certain notions and imaginary geographies of Arab worlds? Specifically, how are foreign places distorted in western culture’s popular images and understandings of the Arabic world?

[Stephen Graham] As Edward Said argued, popular perceptions of Arab cities tap into very long-standing Orientalist tropes suggesting that these cities constitute an Other to the west inhabited by exoticism, deviousness, bestiality and eroticism. All forms of western popular media do little to disavow these Orientalist myths; instead, tropes which essentialise Arab cities as intrinsically terroristic have simply been added to the mix. Western media and military commentators routinely render Iraq’s cities as little but animalistic “terrorist nests”.

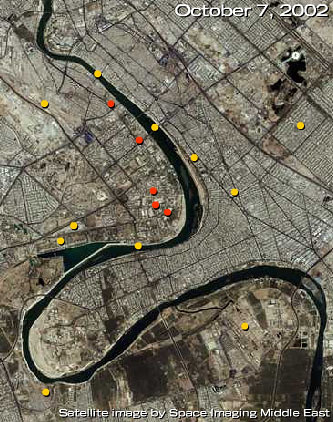

There are two key ways in which Arab cities are portrayed as essentially non-social spaces which need to be unveiled, assaulted and controlled by dominant western military technology. First, as Derek Gregory has argued, the voyeuristic consumption by Western publics of the U.S. and UK urban bombing campaigns -- a dominant feature of the ‘war on terror’ -- is itself based on mediated representations where cities are actually constructed as little more than physical spaces for receiving murderous ordnance. Verticalized web and newspaper maps in the U.S. and UK, for example, have routinely displayed Iraqi cities as little more than impact points where GPS-targeted bombs and missiles are either envisaged to land, or have landed, are grouped along flat, cartographic surfaces. Between 2002-2004, for example, USA Today offered an “interactive map of Downtown Baghdad” on the Web where viewers could click on bombing targets and view detailed satellite images of urban sites both before and after their destruction.

[Image: The USA Today's Interactive Map of Baghdad. Click here to access.]

Meanwhile, the weapons’ actual impacts on the everyday life of ordinary Iraqis or Afghanis, who are caught up in the bombing, as ‘collateral damage’, have been rendered almost invisible by a process of self censorship amongst mainstream western media, combined with U.S. military action. This has happened as part of the U.S. military’s elaborate doctrine of ‘psychological operations’ and ‘information warfare’. In April 2003, for example, such doctrine led U.S. forces to bomb Al-Jazeera’s Baghdad offices because the TV station regularly transmitted street-level images of the dead civilians that resulted from U.S. aerial attacks on Iraqi cities. Through reducing the transnational diffusion of images of Iraqi civilian casualties – a process already limited by the decisions of an overwhelming majority of Western media editors not to display such material – such campaigns operated to further back-up the dominant visual message within the verticalized, satellite-based coverage that dominated the mainstream western media’s treatment of the war, especially during its earlier, bombing dominated, phases.

[Image: Movie trailer for the 2004 documentary film 'Control Room'; also read this relevant Democracy Now! transcript with Amy Goodman and the filmmaker Jehane Noujaim and senior producer for Al Jazeera Samir Khader.]

Such coverage combined to propagate a series of powerful and inter-related myths: that Iraqi cities existed as asocial, completely physical domains, which could be understood from the God-like perspective of remotely-sensed or cartographic imagery; that such cities were, at the same time, somehow devoid of their populations of civilians; and that it was not inevitable that Iraqi civilians would therefore be killed and maimed in large numbers when their cities were subjected to large-scale aerial bombardment (even when this targeting was deemed ‘precise’ through the dominant, verticalized, mediated gaze of Western onlookers). As Derek Gregory suggests in The Colonial Present, in this imaginative geography, which is strongly linked to the wider history of colonial bombing and repression by Western powers, Arab ‘cities’ were thus reduced to the:

“places and people you are about to bomb, to targets, to letters on a map or co-ordinates on a visual display. Then, missiles rain down on K-A-B-U-L, on 34.51861N, 69.15222E, but not on the eviscerated city of Kabul, its buildings already devastated and its population already terrorized by years of grinding war.”

Second, through video games produced by the U.S. military, such as America’s Army and Full Spectrum Warrior, millions of westerners (and others) regularly immerse themselves in stylised renditions of fictional ‘Arab’ cities to fight for ‘freedom’ and cleanse these cities of shadowy ‘terrorists. Both games – which were amongst the world’s most popular video game franchises in 2005 – centre overwhelmingly on the military challenges allegedly involved in occupying and pacifying stylized, Orientalized, Arab cities. Their immersive simulations “propel the player into the world of the gaming industry’s latest fetish: modern urban warfare” (DelPiano, 2004). Andrew Deck (2004) argues that the proliferation of urban warfare games based on actual, ongoing, U.S. military interventions in Arab cities, works to “call forth a cult of ultra-patriotic xenophobes whose greatest joy is to destroy, regardless of how racist, imperialistic, and flimsy the rationale” for the simulated battle.

[Images: From the video game America's Army.]

Such games work powerfully to further reinforce imaginary geographies equating Arab cities with ‘terrorism’ and the need for ‘pacification’ or ‘cleansing’ via U.S. military invasion and occupation. More than further blurring the already fuzzy boundaries separating war from entertainment, they demonstrate that the U.S. entertainment industry “has assumed a posture of co-operation towards a culture of permanent war” (Deck, 2004). Within such games, as with the satellite images and maps discussed above, it is striking that Arab cities are represented merely as “collections of objects not congeries of people” (Gregory, 2004b: 201). When people are represented, almost without exception, they are rendered as the shadowy, subhuman, racialized Arab figure of some absolutely external ‘terrorist’ -- figures to be annihilated repeatedly in sanitized ‘action’ as entertainment, or military training, or both. America’s Army simulates ‘counter terror’ warfare in densely packed Arab cities in a fictional country of ‘Zekistan’. "The mission" of the game, writes Steve O’Hagan (2004):

"is to slaughter evildoers, with something about ‘liberty’ [...] going on in the back ground [...]. These games may be ultra-realistic down to the caliber of the weapons, but when bullets hit flesh people just crumple serenely into a heap. No blood. No exit wounds. No screams"

Here, then, once again, the only discursive space for the everyday sites and spaces of Arab cities is as environments for military engagement. The militarization of the everyday sites, artifacts, and spaces of the simulated city is total. “Cars are used as bombs, bystanders become victims [although they die without spilling blood], houses become headquarters, apartments become lookout points, and anything to be strewn in the street becomes suitable cover” (DelPiano,2004). Indeed, there is some evidence that the actual physical geographies of Arab cities are being digitized to provide the three-dimensional ‘battlespace’ for each game. One games developer, Forterra systems, which also develops training games for the US military, boasts that “we’ve [digitally] built a portion of the downtown area of a large Middle Eastern capital city where we have a significant presence today” (cited in Deck, 2004).

[Image: U.S. ARMY PEO STRI / PROGRAM EXECUTIVE OFFICE for SIMULATION, TRAINING, & INSTRUMENTATION.]

(see Deck, A. (2004) Demilitarizing the playground. No Quarter. (February 2006); DelPiano, S. (2004) Review of Full Spectrum Warrior. Games First, (February 2006); O’Hagan, S. (2004), Recruitment hard drive. Guardian Guide. June 19-25: 12-13.)

[Bryan Finoki] Switching from those kinds of virtual cogs in the war machine let’s talk about the more physical gears of retooling the battlefield. Much has been written about the relationship of urban warfare and the sort of ‘perishibility of colonialism’ that we are witnessing in the urbanization of insurgency. You’ve talked about how modern infrastructure has historically been seen as the triumph of man’s ability to control nature, yet in the context of war infrastructure is the most vulnerable component of the city and ultimately the power of modernism. In this scenario the infrastructure becomes a weapon to be turned back onto itself, and the bane of a city’ own existence.

However, this is not merely an informal tactic on just the part of terrorists. Less attention seems to have been given to the ways more formal sponsors of disruption actually function. I’m curious to hear your thoughts on state-backed disruptions of urban infrastructure that are or are not similar from the insurgent disruptions of city systems. John Robb describes an “open-source warfare” used by the insurgents to swarm the more traditional military paradigms of American super power. Could you elaborate on the state-sponsored acts of infrastructural warfare as thy have grown from the WWII bombing campaigns on urban structures in Europe to the more systematic destructive re-landscaping that we find taking place for example in the West Bank or Iraq?

[Stephen Graham] Actually, state-backed infrastructure disruption is far more damaging than anything that infrastructural insurgents or terrorist could ever hope to achieve. With wholesale carpet bombing of civilians now illegitimate, militaries such as the US and IDF now bring coercive pressures to bear on whole city populations by demodernising cities and deliberately ‘switching off’ the circuits essential to modern urban life. This is justified because urban infrastructures are deemed to be ‘dual use’ in international law. This has been called the strategy of ‘bomb now, die later’ or the ‘war on public health’.

Israel has perfected this with its D9 bulldozers and systematic attacks on Palestinian and Lebanese airports, electricity systems, bridges, ports and water systems. The US has developed a family of non-explosive bombs deliberately designed to short-out entire electrical systems. It also has very powerful Electronic pulse weapons to ‘fry’ computers and electrical systems.

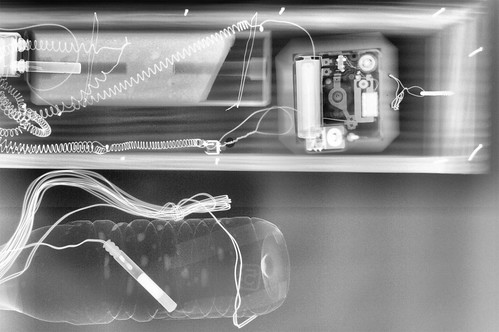

Underpinning US infrastructural warfare strategy is the notion of the "enemy as a system". A doctrine that developed from the “industrial web” ideas used to shape Allied bombing in World war II, this doctrine was devised by a leading US Air Force strategist, John Warden, within what he termed his strategic ring theory (1995) and has been the central strategic idea driving all major US bombing campaigns since the late 1980s. This systematic view of adversary societies, which builds directly on the industrial web theorisation of US air power strategists in World War II, provides the central US strategic theorisation that justifies, and sustains, the rapid extension of that nation’s infrastructural warfare capability.

"At the strategic level," writes Warden, "we attain our objectives by causing such changes to one or more parts of the enemy's physical system" (1995). This 'system' is seen to have five parts or rings: the leadership or 'brain' at the centre; organic essentials (food, energy, etc); infrastructure (vital connections like roads, electricity, telecommunications, water etc.); the civilian population; and finally, and least important, the military fighting force (Felker,1998).

[Image: Warden’s strategic ring theory.]

Rejecting the direct targeting of enemy civilians, Warden, instead, argues that only indirect attacks on civilians are legitimate. These operate through the targeting of societal infrastructures - a means of bringing intolerable pressures to bear on the nation's political leaders. This doctrine now officially shapes the projection of US aerial power and underpins the key U.S Air Force doctrine document – 2-12 – published in 1998 (USAF, 1998). Warden (1996, 6), recalling its centrality to the Iraq and Kosovo campaigns that we’ll explore shortly, outlines how the ‘Strategic Ring Theory’ shapes the targeting of infrastructure. “When we want more information” [about an adversary society], he writes, “we pull out subsystems like electric power under system [‘organic’] essentials and how it as a five-ring system. We may have to make several more five-ring models to show successively lower electrical subsystem. We continue the process until we have sufficient understanding to act” (i.e. make targeting decisions).

Kenneth Rizer, another U.S. air power strategist, recently wrote an extremely telling article in the official US Air Force Journal Air and Space Power Chronicles. In it, he seeks to justify the direct destruction of dual-use targets (i.e. civilian infrastructures) within U.S. strategy. Rizer argued that, in international law, the legality of attacking dual-use targets "is very much a mater of interpretation" (2001, 1).

Rizer writes that the US military applied Warden's ideas in the 1991 air war in Iraq with, he claims, "amazing results". "Despite dropping 88,000 tons in the 43 day campaign, only 3000 civilians died directly as a result of the attacks, the lowest number of deaths from a major bombing campaign in the history of warfare" (2001, 10). However, he also openly admits that -- as we shall soon discuss -- the United State's systematic destruction of Iraq's electrical system in 1991 "shut down water purification and sewage treatment plants, resulting in epidemics of gastro-enteritis, cholera, and typhoid, leading to perhaps as many as 100,000 civilian deaths and the doubling infant mortality rates" (2001, 1).

Clearly, however, such ‘indirect ‘deaths are of little concern to US Air Force strategists. For Rizer openly admits that:

"The US Air Force perspective is that when attacking power sources, transportation networks, and telecommunications systems, distinguishing between the military and civilian aspects of these facilities is virtually impossible. [But] since these targets remain critical military nodes within the second and third ring of Warden's model, they are viewed as legitimate military targets […] The Air Force does not consider the long-term, indirect effects of such attacks when it applies proportionality [ideas] to the expected military gain" (2001, 10).

More tellingly still, Rizer goes on to reflect on how US air power is supposed to influence the morale of enemy civilians if they can no longer be carpet-bombed. "How does the Air Force intend to undermine civilian morale without having an intent to injure, kill, or destroy civilian lives?" he asks:

"Perhaps the real answer is that by declaring dual-use targets legitimate military objectives, the Air Force can directly target civilian morale. In sum, so long as the Air Force includes civilian morale as a legitimate military target, it will aggressively maintain a right to attack dual-use targets" (ibid. 11).

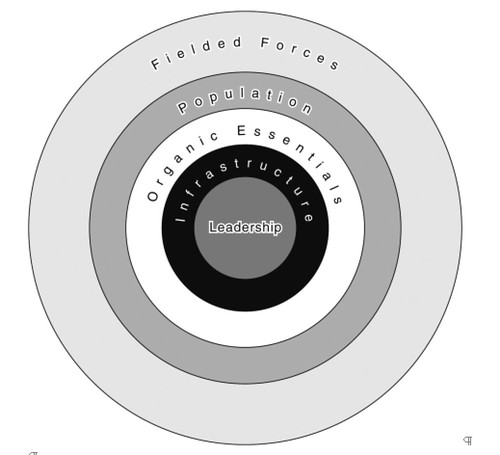

In 1998 Edward Felker – a third US air power theorist, like both Warden and Rizer, is based at the U.S. Air War College Air University – further developed Walden's model. This was based on the experience of Desert Storm, and drew on Felker's argument that urban infrastructure, rather than a separate 'ring' of the 'enemy as a system', in fact pervaded, and connected, all the others to actually "constitute the society as a whole". "If infrastructure links the subsystems of a society," wrote Felker, "might it be the most important target?" (1998, 20).

[Image: Felker’s modification of strategic ring theory.]

In practice, state infrastructural attacks against modern urban societies are devastating. In urban societies, there are few alternatives once the food can’t be shipped in, the electricity goes off, the water and sewerage pumps stop working, and the wastes can no longer be removed. Very quickly, the poor, the weak and the old succumb to water borne diseases. Following the total destruction of Iraq’s electric system in the First Gulf war in 1991, foe example, Colin Rowat, of the Oxford Research Group, has calculated that:

"the number of Iraqis who died in 1991 from the effects of the Gulf war or postwar turmoil approximates 205,500. There were relatively few deaths (approximately 56,000 military personnel and 3,500 civilian) from direct war affects. The largest component of deaths derives from the 111,000 attributable to postwar adverse health effects" (Rowat, 2002)

Using a longer time-frame, UNICEF (1999) reported that, between 1991 and 1998, there were, statistically, over 500,000 excess deaths amongst Iraqi children under five -- a six-fold increase in death rates for this group occurred between 1990 and 1994. Such figures mean that, "in most parts of the Islamic world, the sanctions campaign is considered genocidal" (Smith, 2002, 365). The majority of deaths, from preventable, waterborne diseases, were aided by the weakness brought about by widespread malnutrition. The World Health Organisation reported in 1996 that:

"the extensive destruction of electricity generating plants, water purification and sewage treatment plants during the six-week 1991 war, and the subsequent delayed or incomplete repair of these facilities, leading to a lack of personal hygiene, have been responsible for an explosive rise in the incidence of enteric infections, such as cholera an typhoid" (cited in Blakeley 2003a, 23).

According to William Church, ex-Director of the Center for Infrastructural Warfare Studies, the next frontier of infrastructural warfare will involve nation states developing the capacity to undertake the types of coordinated ‘cyberterror’ attacks that they are so comprehensively mobilising against. "The challenge here," he writes, "is to break into the computer systems that control a country's infrastructure, with the result that the civilian infrastructure of a nation would be held hostage" (Church, 2000, 3). Church argues that NATO considered such tactics in Kosovo and that the idea of cutting Yugoslavia's internet connections were raised at NATO planning meetings, but that NATO rejected these tactics as problematic. But, within the United State's emerging doctrine of Integrated Information Operations and infrastructural warfare – which involve everything from destroying electric plants, dropping Electronic Magnetic Pulse (EMP) bombs which destroy all electrical equipment within a wide area and developing globe-spanning surveillance systems like Echelon, to dropping leaflets and disabling web sites – a dedicated capacity to use software systems to attacks opponent's critical infrastructures is now under rapid development.

[Image: ECHELON, UK.]

Deliberately manipulating computer systems to disable opponent's civilian infrastructure is being labeled Computer Network Attack (or CNA) by the U.S. military. It is being widely seen as a powerful new weapon, an element of the wider 'Full Spectrum Dominance' strategy. Drawing again on Walden's Ring Theory, and its derivatives, Kelley, (1996) -- author of a major US Air Force strategy document Air Force 2025 -- outlines the rationale:

"the information warfare battlespace is the information-dependent global system of systems of which most of the strengths, weaknesses, and centers of gravity of an adversary's military, political, social and economic infrastructure depend. That is, not only must the question 'What and where are the data on which these infrastructures depend ?' be answered, but, equally important, we must ask 'what are the structures and patterns of human activity depending on these databases and communications infrastructures ?' Information attack requires more than a knowledge of wires." (2)

(See Blakeley R. (2003), Bomb Now, Die Later. Bristol University : Department of Politics, February 2004; Church, W. (2000), “Kosovo and the future of information operations.” (February 2004).; Felker, E. (1998), Airpower, Chaos and Infrastructure : Lords of the Rings, U.S. Air War College Air University, Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama, Maxwell paper 14, July; Kelly, J. (1996), Air Force 2025, U.S. Air War College Air University, Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama; Rizer, K. (2001), “Bombing dual-use targets : Legal, ethical, and doctrinal perspectives,” Air and Space Power Chronicles, 5th January, (February 2004).; Smith, T. (2002), “The new law of war : Legitimizing hi-tech and infrastructural violence,” International Studies Quarterly, 46, 355-374.; United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF)(1999), Annex II of S/1999/356, Section 18, February 2004); Warden, J. (1995), “The enemy as a system,” Airpower Journal, 9 (1), 41-55.)

[Bryan Finoki] And then we can even consider different forms of state-sponsored disruption used on the homeland as well. I am thinking for example the entire Enron scandal where the power companies literally hijacked California by causing power outages and manipulating the energy market while pushing for an unregulated energy policy. So, it is not only a tactic for war but also a domestic political economic tool as well. How do you see the state-backed infrastructure disruption tactic being internalized this way as well?

[Stephen Graham] The California case certainly was an extreme example of the corporate takeover of key ‘public’ infrastructure and the possibilities of corporate corruption through deliberate disruption and ‘shock treatment’. It was also a microcosm of the dangers of forcibly reengineering public infrastructures through the application of extreme and completely inappropriate neoliberal ideologies – a saga repeated through many ‘structural adjustment’ policies in the global south and Eastern Europe in the last few decades.

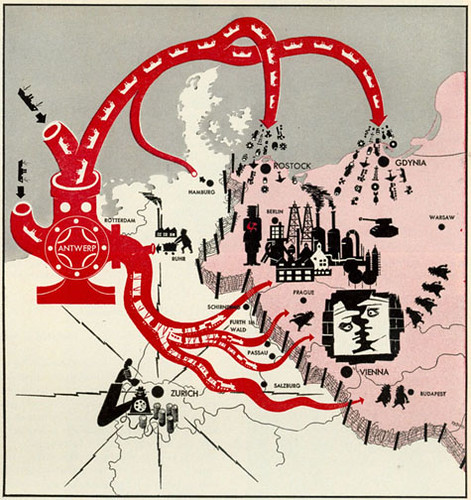

Image: Antwerp as a Colossal Octopus Pump (Image 3). Life Magazine, 26 January, 1953 via Space and Culture.]

Even the interests of capital have started to mobilize against the problems of trying to compete in a ‘globalised’ or ‘networked’ society using infrastructure systems that have been splintered off, commodified and reengineered to serve the profit demands of corporate owners. On the other hand, the costs of small disruptions in stock markets, electronic trading, and global logistics circuits means that many states are trying to find ways of re-regulating private infrastructure operators so that such disruptions are minimized.

[Bryan Finoki] If we accept that militarism necessitates the political boundaries of an inside and an outside constantly casting the conflict zone as some ‘other’ place beyond the sovereign territory of the nation-state, then it’s interesting to see how this new military urbanism both consecrates the physical borders of nation states as well the network infrastructure that allows transnationalism to flourish where borders are theoretically less relevant. There seems to be a contradiction within this type of spatial militarization that simultaneously cements the “other” across the board in urban and geographic patterns while also paradoxically serving the higher ‘inclusive’ structures of global capital.

With that in mind, how have conflict zones abroad been re-incorporated into the domestic fabric of the city, or inside the nation rather than merely existing as a space outside of national sovereignty? Is part of the effect of globalization with the spread of capital and military investment a new internalization of the conflict zone?

[Stephen Graham] There are huge contradictions here. The key is the shifting line that is continually being drawn between the consecrated and celebrated mobilities of people, information, capital and goods (“good” globalization) and those mobilities, people, and bodies that are rendered illegitimate, pathological, or malign. Huge political opportunism is always at work here, taking advantage of latent racisms and the symbolic demonisation of large swathes of the non-white world within popular culture and media. Thus, whilst many core industries in North America would grind to a halt without the ability to exploit cheap ‘illegal’ migrants – agriculture, tourism, construction, child care, textiles, restaurants etc. – the mobilities of the people who risk everything to come and supply that labour must also be continually attacked and demonised. This labour is fine as long as it is invisible and operates in the interstices of urban space.

[Image: ECHELON, UK.]

The changing geographies and architectures of borders also fit with this altered idea of the ‘inside’ and outside’ of nations. Instead of a Euclidean geometry of territorial states occupying all the space of the world and organising their mutual borders, we are seeing the emergence of what we might call the global border assemblage. This is organised through architectural and digital technologies of control which are layed out along the key lines of mobility – usually city to city. It operates through the continuous surveillance, tracking, profiling and marking of bodies, goods , information and capital, and an attempt to separate out legitimate from illegitimate ones. It is preemptive as it links databases and profiles into continuous imaginations of the near future. And it both enters the internal space of nations and extends beyond their territorial borders. So, for example, US immigration and port policy now extends way beyond US borders as it strives to reshape practice in the airports and ports of all the main trading partners. Meanwhile, new borders are being enacted within nations, as certain districts are profiled and surveilled for terrorist sympathizers or those deemed insufficiently patriotic. We should also not forget the global ‘shadow space’ of rendition made up of airports, CIA torture centres and other archipelagos of exception.

Perhaps this is a post-citizenship world based on profiling, tracking and risk assessment rather than standardized national entitlement and political rights? The US recently talked to the UK government about having different visa arrangements for US nationals with Pakistani links or origins to those of the rest of the UK citizenry.

[Image: Deconstruction | 2007 | Almost Safe Series. Photo by Anthony Goicolea.]

[Bryan Finoki] As you know, I am trying to explore the geographies of what I refer to as counter-empire landscapes, by this I mean spaces not just of resistance, subversion, or a circumnavigation of western militaristic hegemony (i.e. border and smuggler tunnels, high seas piracy, the urbanization of insurgency, etc.), but ultimately spaces of colonial capitalist resistance – spaces, that perhaps, are born out of the erosions in the spatial logic of a securitized nation-state border. This could be day-laborer spaces, new sites of political activism, network space, and other hybrid geographies of critical spatial practice that include art and different informalities of community design.

Where do you see the greatest sort of spatial backlash to current colonial forms of militarism? Spatially, how do you see globalization progressing?

[Stephen Graham] I think the things you are looking at – and it’s a fascinating project – might best be seen as a parallel 'unbordering' assemblage that follows, and works to undermine, the state, military and commercially-led global bordering assemblage I discuss above. These various spaces and networks of insurgent citizenship, resistance, activism and militancy that you talk about work, erupt within -- and, especially, below -- the infrastructures of mobility and control of the global bordering assemblage. So here is the spatial backlash that you talk about. I think Keller Easterling’s work, in her book, Enduring Innocence, captures the counter and mainstream geographies and architectures of control really well.

[Bryan Finoki] What can we predict about the future and the way cities will look, the ways they will be planned and function, say, 400 years from now, in light of all this defensive design? Will they further devolve into economic engines for imperialism, militarized slums, half preserved in ruins, perpetual conflict, urbicide, crumbled under the strategic weight of the Pentagon's networked battlespaces? Or, can the Third World help bring forth new models of an 'anti-imperialist urban regime'? Not just localized cities of resistance, or bunkers for an urbanized insurgency, but post-imperial, post-capital cities reinvented out of Empire in a new egalitarian form, beyond the uneven wealth distribution that cities seemed to have served through out history? What will the cities of a post-Empire landscape look like, how will they function, how will they be governed, and more interestingly, how will they emerge?

[Stephen Graham] I think smart materials, nano technology and biotechnology will increasingly be woven into the architectures and geographies of cities in ways that make securitisation a great deal more stealthy than occurs now. In other words, Deleuze’s ‘Societies of Control’ are set to massively intensify. As ‘ambient intelligence’ and embedded or ‘ubiquitous computing’ become the means to orchestrate the world, formal defensive design may thus increasingly become more of a symbolic marker – a signifier of status, centrality and commercial power. The real architectures of control, already, are algorithms, software, databases and microelectronic tracking systems, satellites and sensors, linked intimately to physical spaces, infrastructures, and bodies, rather than the obvious architectonic brute force of walls and ramparts.

[Image: North Bank | 2007 | Almost Safe Series. Photo by Anthony Goicolea.]

In the longer term and broader context, I think that, strategically, we’re going to be moving back towards a multi-polar world. I think US power will wane as its military dominance will be increasingly difficult to sustain, especially with the chronic balance of payments problems, economic mismanagement, resource depletion and the externalization of more and more high value-added activities to Asia. China, and India, too, are likely to emerge as major economic and military superpowers and their militaries will move rapidly towards the high-technology control architectures currently almost monopolised by the US. China, already, is very active in many parts of Africa and the Middle East in quasi-colonial roles.

So, instead of some 'anti-imperialist urban regime,’ I think we’re likely to see contesting transnational architectures of imperial urbanism centred on the extraction and control of key resources (oil, water, unflooded land, food, technology); the organizing of transnational capital circuits of accumulation, trade, labour exploitation and migration; and the military control of key spaces and corridors linking (urbanising) terrain with the critical vector of aerial and space power.

[End of Pt. 2: Bryan Finoki / Stephen Graham, 2007]

Earlier: The City in the Crosshairs: A Conversation with Stephen Graham (pt. 1)

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home