Conflict Signatures and Nomadic Light

[Image: Defense Meteorological Satellite Program – Operational Linescan System imagery from the F16 satellite. Image and data processing by NOAA’s National Geophysical Data Center. DMSP data collected by the US Air Force Weather Agency. (John Agnew/Environment and Planning).]

Researchers from UCLA are questioning some of the success claimed by the surge in Baghdad based on data they’ve discerned from some satellite images.

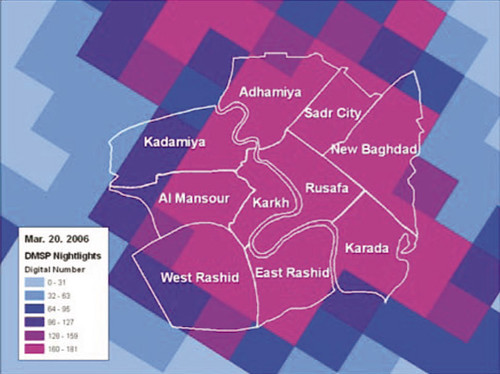

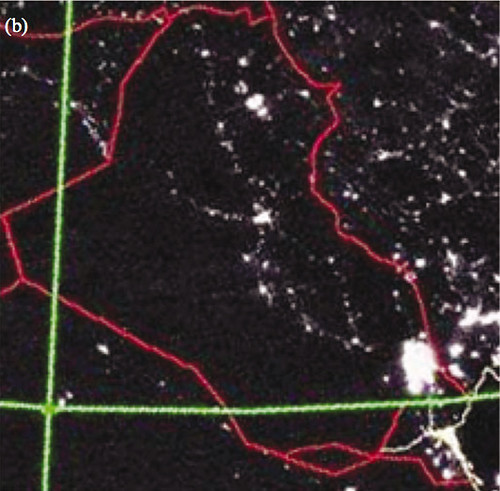

By comparing the amount of light produced at night in different areas of the capital before, during and after the 30,000 extra troops had been deployed, researchers from UCLA were able to track the movements of the warring Sunni and Shiite factions.

The amount of light was assumed to reflect the number of lights switched on in an area. Combining that with a map of neighbourhood boundaries showed that the lights had dimmed much more in the Sunni dominated west and south-western regions of Baghdad.

But this change began before the influx of extra troops. The light levels in four other major cities untouched by the surge remained constant or increased during the period.

If what the research suggests – that part of the surge’s success in these neighborhoods relies on some of the ethnic cleansing of Sunni’s by rival Shiites that happened prior to the injection of U.S. troops -- is one day more confirmed, and the surge actually piggybacks on the success of sectarian bloodshed, then this type of research could have huge implications. Was the surge successful, or was it just a tactic for profiting off of some post-violence calm?

“If the surge has truly ‘worked’ we would expect to see a steady increase in nighttime light over time, as electrical infrastructure is repaired and restored, with little discrimination across neighborhoods.”

[Image: The light emitted from areas of Baghdad soon after the beginning of the war (top), months prior to the surge (middle), and after the surge (bottom), indicate that the lights started going off before the increase in US troops – particularly in the south and west, Sunni, districts. Each square represents 3 square miles (John Agnew/Environment and Planning) - (Via: New Scientist) .]

"Essentially, our interpretation is that violence has declined in Baghdad because of intercommunal violence that reached a climax as the surge was beginning," said lead author John Agnew, a UCLA professor of geography and authority on ethnic conflict. "By the launch of the surge, many of the targets of conflict had either been killed or fled the country, and they turned off the lights when they left."

That’s awesome. What a way to put the surge in to perspective.

You can read more about how the research was conducted and compared against other cities whose night-light signatures remained steady during the time of the surge, right here, the official findings of which will be published in Environment and Planning in October. (See abstract here for now)

[Image: Defense Meteorological Satellite Program – Operational Linescan System imagery from the F16 satellite. Image and data processing by NOAA’s National Geophysical Data Center. DMSP data collected by the US Air Force Weather Agency. (John Agnew/Environment and Planning).]

Of course, I’m in no position to speculate on what these images really mean, but John Agnew certainly alights some interesting questions about the different ways we can or cannot measure the footprints of conflict and resolution reliably, and how satellite images could perhaps be used to scrutinize government claims.

I mean, what is the official criterion for measuring the surge’s success, anyway? And how do we know that the answer to that question (however decided upon) can’t, or hasn’t been reached through other means? In the age of the drone and omnipotent satellite surveillance, it seems awfully critical to find ways of investigating the aerial perspective not only as a way to truly evidence the surge’s success, or failure, for that matter – but as a larger way of holding the government accountable.

Maybe I just love the notion of keeping U.S. military officials on their toes, watching where they don’t expect to be seen, decoding the Baghdad landscape in ways they never thought would run counter to their position. But, this type of work (though I am not sure of it’s true potential) seems vital to public oversight of military action and reliability, I don’t know.

It will be more telling to see this type of image analysis evolve over the course of different conflicts in the future.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home