Torture Space: Architecture in Black

[Image: Photo by Richard Ross in his amazing collection, Architecture of Authority

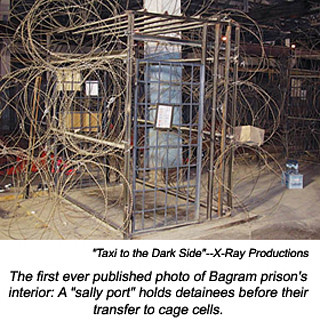

Well, no better way to measure secret space then through first hand account, right? These renderings were based on drawings by a Yemeni man, Mohamed Farag Ahmad Bashmilah, a former ghost detainee in the CIA’s extraordinary rendition program for a nightmarish19 months. His story is grim, to say the least – difficult to even read. But who knows, maybe even more common than we know. In fact, I think the whole rendition universe has got to be one of the most unfathomable realities ever to stalk the planet – it is impossible for me to even reason. Anyone who has been following details of the whole thing probably knows his story by now.

Salon Magazine published these images in a harrowing interview with Bashmilah back in December last year, and I can’t help but to repost them here. Not because they are terribly riveting, or revealing in any architectural way. But, mostly for what they represent – blueprints of a secret torture underworld through the eyes of a survivor.

[Image: Architecture of detention, Salon, 2007.]

Bashmilah says he was originally snagged, held, and beaten in Jordan in 2003, before being transferred to a prison in Afghanistan, he later gathered, where he was tortured so mercilessly he tried to commit suicide several times. Attempting to starve himself to death he was injected with a feeding tube by the CIA (a practice also used on starving protestors inside Guantanamo Bay), and kept alive so that he could experience, in Margaret Satterthwaite’s words (an attorney for Bashmilah, and a professor at the New York University School of Law), "psychological torture and the experience of being disappeared."

“Bashmilah said in the phone interview that the psychological anguish inside a CIA black site is exacerbated by the unfathomable unknowns for the prisoners. While he figured out that he was being held by Americans, Bashmilah did not know for sure why, where he was, or whether he would ever see his family again.”That alone sounds about like the most frightening space a human being could possibly find themselves in: an indefinite space of disappearance, not even death, or a place where one knew they were going to die seems as bad to me. But, to just be disappeared; a prisoner of totally unknown conditions, snatched from the whereabouts of the rest of the world. It’s almost worse than death itself. It’s serial kidnapping and torture at the highest degree. To systematically construct places for such a purpose. To hang in that balance alone even before any additional torture has taken place on top of it, seems to me like perhaps the cruelest basis for any form of human existence. To be the subject of “a regime of imprisonment designed to inflict extreme psychological anguish,” as the Salon put it. Can life be spent any worse than that?

[Image: CIA Rendition and covert aircraft still using Shannon airport.]

As part of a lawsuit filed by the ACLU on behalf of three other victims against Jeppesen Dataplan Inc. (a subsidiary of Boeing accused of facilitating secret CIA rendition flights), Bashmilah provided drawings of the interiors of the CIA’s black site as best as he could recall. To think, how inscribed the dimensions of his torture chambers are on his psyche now, is beyond me. Sure, there are the physical spatial dimensions of torture, but how does an innocent victim of such an incomprehensible experience psychologically store and move on from that? I wonder if the act of making his drawings was cathartic for him, or not?

[Image: Architecture of detention, Salon, 2007.]

Here is part of his narrative that will no doubt forever reside in the simple mundane lines of these basic CAD drawings. From a subtopian perspective, could a simple drawing ever contain any more political significance?

After a short car ride to a building at the airport, Bashmilah's clothes were cut off by black-clad, masked guards wearing surgical gloves. He was beaten. One guard stuck his finger in Bashmilah's anus. He was dressed in a diaper, blue shirt and pants. Blindfolded and wearing earmuffs, he was then chained and hooded and strapped to a gurney in an airplane.That is a glimpse of the CIA’s nomadic rendition infrastructure. One moment, reminiscent of Bran Castle’s abominable underground dungeons from the 13th century, another, it appears like an unfinished prison cell in the armpit of maximum security America.

He was then placed in a windowless, freezing-cold cell, roughly 6.5 feet by 10 feet. There was a foam mattress, one blanket, and a bucket for a toilet that was emptied once a day. A bare light bulb stayed on constantly. A camera was mounted above a solid metal door. For the first month, loud rap and Arabic music was piped into his cell, 24 hours a day, through a hole opposite the door. His leg shackles were chained to the wall. The guards would not let him sleep, forcing Bashmilah to raise his hand every half hour to prove he was still awake.

Cells were lined up next to each other with spaces in between. Higher above the low ceilings of the cells appeared to be another ceiling, as if the prison were inside an airplane hanger.

[…] the small cells were all pretty similar, maybe 7 feet wide and 10 feet long. He was sometimes naked, and sometimes handcuffed for weeks at a time. In one cell his ankle was chained to a bolt in the floor. There was a small toilet. In another cell there was just a bucket. Video cameras recorded his every move. The lights always stayed on -- there was no day or night. A speaker blasted him with continuous white noise, or rap music, 24 hours a day.” […]

after six months he was transferred, with no warning or explanation. … black-masked guards again put him in a diaper, cotton pants and shirt. He was blindfolded, shackled, hooded, forced to wear headphones, and stacked, lying down, in a jeep with other detainees. Then he remembers being forced up steps into a waiting airplane for a flight that lasted several hours, followed by several hours on the floor of a helicopter. […]

He was then thrown into a cold cell, left naked.

It was another tiny cell, new or refurbished with a stainless steel sink and toilet. Until clothes arrived several days later, Bashmilah huddled in a blanket. In this cell there were two video cameras, one mounted above the door and the other in a wall. Also above the door was a speaker. White noise, like static, was pumped in constantly, day and night. He spent the first month in handcuffs. In this cell his ankle was attached to a 110-link chain attached to a bolt on the floor.

The door had a small opening in the bottom through which food would appear: boiled rice, sliced meat and bread, triangles of cheese, boiled potato, slices of tomato and olives, served on a plastic plate.

One thing, though, about the concept of torture space that freaks me out as I give it more attention is not only how eerie its design may be with an architectural intent to inflict misery on its occupant, but how frighteningly suggestive torture space is of the mentality of the designer itself. If architecture is any sort of psychological mold or mirror, then what torture space says about those who create it (either by design or in some momentary whim of dismal improvisation) creeps me out even more so than what the space implies for the psychology of the one who must be forced to endure it. And what about those guards and jailers who inhabit the detention centers on the other side of torture? How quickly we forget the dehumanization they are subjected to as well. Man, the whole thing just reeks of some Ballardian pscyhoarchitectural disease – for ALL involved.

[Image: Photo by Richard Ross in his amazing collection, Architecture of Authority

Be that as it may, I must confess, in another book I’d love to read, or even miraculously research and somehow manage to write one day myself, I’d be interested in tracking how torture has always existed as a form of architecture, and as a political site – a political geography; meaning not just as a place on the map but as a space constituted by the political system in which it was embedded at the time. In other words, what is the architectural and political history of torture space? Or, inversely, what is the role torture has played in the development of the world’s legal and political systems? Or, how has torture pushed the progress of architectural, or urban space? Has the practice of torture always exerted some influence over the evolution of different judicial systems, corrective spaces, etc.? Are some of the earliest designs of secret space owed to the hand of torture?

I obviously lack at this point considerable knowledge on the topic (much catching up to do, I’m afraid), but I wonder, if by tracing a spatial legacy of torture through out history what we might be able to learn about the nature of politics and the spaces engendered by that? Where does torture come from psychologically, culturally, perhaps even sexually? Is there a correlation between torture space and how spaces of gender have always manifested? Torture was so often linked to religion and persecution, I’m so curious to go back and look at how religious forms of space have represented this, if at all – the architectural iconography of torture. How do sites of torture come to be produced in certain political environments, and how has the nature of torture space shifted politically over time?

I don’t know, maybe those aren’t even questions worth pursuing, but, I am going to keep them stewing in the Subtopian cauldron, anyway.

[Image: Photo by Richard Ross in his amazing collection, Architecture of Authority

I guess I’m also curious if through a spatial lens we could more clearly see specifically how torture has been systematized, institutionalized, and diffused within the modern legal landscape of sovereignty and state power. So while we acknowledge that torture today takes place within these "black sites," how did it get there, away from the public exhibition of torture back in the dark days of medieval spectacle? Torture itself may have evolved only very little over time but has certainly stayed as constant as any other narrative through out humanity’s course of behavior. I’m just fascinated, architecturally speaking, by the steps torture space took to retreat into secrecy. With that said, I need to learn more about the militant machinations that have helped to disguise torture space, or even incorporate it within the fabric of the domestic landscape over time.

Sorry for my typical babbles here, but in simplest terms: what is there to learn by retracing an urban, or architectural morphology of torture? How did we get from the Brazen Bull in ancient Greece to getting off on Hollywood flicks about fully blown comedic psychos hacking apart spring break campers in the woods, in our living rooms of all places?

Another dimension to the CIA’s space of torture that admittedly fascinates me on some primal level has been the use of sound and music to drive detainees crazy. It’s been covered by the media already.

Suzanne Cusick wrote a very interesting piece about it tracing the modern history of music in this brutal context, but first dispelled any assumptions we may have had about the value of exploiting sound in regular warfare scenarios, or that sonic weapons and musicological devices have played a significant role in war. Instead, she starts by suggesting something that seems born straight out of the movies. I mean, literally lifted from that classic scene in Apocalypse Now. You know the one, that infamous orchestral helicopter assault with Wagner's Ride of the Valkyries preying over a Vietnamese village.

[Image: From Apocalypse Now. The embedding feature was enabled on for this video, so go here to view it on You Tube.]

She writes:

“Most likely, LRADs (Long Range Acoustic Device) were the means by which the 361st PsyOps company “prepared the battlefield” for the November 2004 siege of Fallujah by bombarding the city with music–supposedly, with Metallica’s “Hells’ Bells” and “Shoot to Thrill” among other things (DeGregory 2004). PsyOps spokesman Ben Abel explained to reporter Lane DeGregory of the St. Petersburg (Florida) Times, “These harassment missions work especially well in urban settings like Fallujah. The sounds just keep reverberating off the walls.” Abel added “it’s not the music so much as the sound. It’s like throwing a smoke bomb. The aim is to disorient and confuse the enemy to gain a tactical advantage” (DeGregory 2004). Abel made clear that although the tactic of bombarding the enemy with sound was made at the command level, the choice of music was left to soldiers in the field: “...our guys have been getting really creative in finding sounds they think would make the enemy upset...These guys have their own mini-disc players, with their own music, plus hundreds of downloaded sounds. It’s kind of personal preference how they choose the songs. We’ve got very young guys making these decisions” (DeGregory 2004). On the battlefield, then, the use of music as a weapon is perceived to be incidental to the use of sound’s ability to affect a person’s spatial orientation, sense of balance, and physical coordination. It is because music is incidental that the choice of repertoire is delegated to individual PsyOps soldiers’ creativity.”Well, needless to say, if I were a musician and found out that my stupid hit track was making an international appearance as a symphonically blasted terrorizing tactic over Fallujah, or as some prelude to attack just before the U.S. military was about to invade a city, I think I’d first puke all over the place and then launch a major lawsuit against the American government. Not that I should complain about my music being licensed for torture, or anything. It’s just that Subtopia don’t surf!

[Image: Photo by Richard Ross in his amazing collection, Architecture of Authority

Anyway, she then cites Alfred McCoy’s fairly recent book A Question of Torture: CIA Interrogation, from the Cold War to the War on Terror

Man, I have so much learning to do! “Concerned by Soviet success at “brainwashing” captives and destroying their wills,” she continues, “these agencies supported research at Yale, Cornell, and McGill intended to learn how we might do the same.”

Forgive the heavy quoting, but apparently during the 1950s this research focused on three areas, one being “the devastating impact of sensory deprivation and sensory manipulation–which would eventually include hooding; continuous noise (whether loud or not) and its opposite, soundproofing”, among other facets of “temporal disorientation.”

[Image: Photo by Richard Ross in his amazing collection, Architecture of Authority

McCoy himself wrote an absolute essential piece of reading on this topic for Tomgram, entitled The Hidden History of Torture. “The CIA's torture experimentation of the 1950s and early 1960s was codified in 1963 in a succinct, secret instructional booklet on torture -- the "KUBARK Counterintelligence Interrogation" manual, which would become the basis for a new method of torture disseminated globally over the next three decades.” And he tracks it all – seriously, go read this article now.

So, the blaring playlists we read about, including anthems from good old Bruce Springsteen and the Bee Gees, that sound for hours on end at Guantanamo Bay, are actually just the continuation of a short legacy of experimental musical torture that’s been explored and practiced for decades now under the verbiage of a “no touch torture” program aimed at exploiting cultural humiliation as a fair game torture tactic.

And we all know how incredibly powerful music can be, spiritual even, especially for some cultures, like Middle Eastern and African perhaps more so than others. The idea of harnessing that power against someone in a truly helpless state is just purely wicked.

[Image: Photo by Richard Ross in his amazing collection, Architecture of Authority

Cusick then does a good job of listing several reported cases when music has been used by Americans in the War on Terror as an interrogation device, from Guantanamo Bay, to Iraq and Afghanistan where one prisoner was “forced to listen to music by Eminem (Slim Shady) and Dr Dre for twenty days before the music was replaced by “horrible ghost laughter and Halloween sounds.””

I think listening to any repetitive music that long would drive anyone insane, don’t you? Hell, if the television commercials aren’t immediately muted, I will snap!

In Iraq, she points us to a 2006 New York Times piece that claimed American “Jailers often blared rap music or rock 'n' roll at deafening decibels over a loudspeaker to unnerve their subjects” and high-value detainees who were sent to a so-called “Black Room” for this very purpose. “The Black Room” we are told, “was part of a temporary detention site at Camp Nama, the secret headquarters of a shadowy military unit known as Task Force 6-26. Located at Baghdad International Airport, the camp was the first stop for many insurgents on their way to the Abu Ghraib prison a few miles away.”

Reading on, this Black Room was described as “a garage-sized, windowless space painted black” where deafening tunes could be used to terrorize the nervous system and tense the body of a detainee already strung up in various stress positions, “in a pitch-black space,” nonetheless, “made uncomfortably hot or cold.” Camp Nana, where the motto was “No Blood, No Foul” (and for all I know may still be) seems like a mere tip of the iceberg to what we continue to see emerging today with regards to the rendition program and other spaces of detention and interrogation.

[Image: Photo by Richard Ross in his amazing collection, Architecture of Authority

Anyway, it goes beyond at this point even calling it Orwellian – it’s utterly psychotic – the wallpaper music of torture space – which actually reminds me of a small piece Goeff penned on BLDGBLOG about assembling Soundtracks for Architecture.

Toying with the phenomenon of lingering musical effects that remain audible in the ambient sounds of our physical locations after we’ve turned the music off, Geoff mused on how cool it might be if a convincing architectural effect could be achieved purely through our music listening; an imaginary supplement that would enhance, or build upon our immediate surroundings. “Music as the illusion of architecture,” he said. “Architecture through nothing but sound. […] So instead of an addition, or a home renovation – you would commission a piece of music; and for as long as that music is playing, your house has several thousand more square-feet.”

[Image: Photo by Richard Ross in his amazing collection, Architecture of Authority

It is appalling to even consider how such a prospect might translate in the world of torture. Instead of jailers playing popular music, or other sound effects that escape our knowledge at this point, you wonder if the Pentagon hasn’t solicited a contract for their own brand of Muzak, or hired a sinister group of sound designers, or some really dark experimental musical prodigies to explore certain psychological spheres of sonic perception specifically tailored for improving and maximizing the mental torture effect.

Will the CIA develop torture soundtracks at some point, so that detention space itself might even become totally secondary to the experience of interrogation and abuse? Forget the specifics of the prison cell, just force them to listen to some soundtrack, and just like that, detainees are signing their lives away to accusations and crimes they have no idea ever even existed! Will the new architecture of torture be a score of abstract noise? Will the CIA’s black world soon be hosting entire concerts of torture?

Another thing, real quick: the only imaginable space I suspect would be as bad – if not worse – than any torture chamber would have to be those places where torture techniques – or any techniques remotely close to torture – are being taught. Certainly, the U.S. government denies torture related tactics are being instructed at their training facilities on intelligence gathering and interrogation at the Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation at Fort Benning (formerly known as the School of the Americas), which has been accused of teaching torture methods to Latin American militaries for years; or, at Fort Huachuca in Arizona where, as Brenda Norrell (one of the most important journalists in my book) wrote, “It was here that the root of the torture manuals were produced that led to the rape, disappearance, torture and murder of an unknown number of Indigenous Peoples and innocent farmers in Central and South America, before the manual was exposed in 1996.”

Bill Quigley had this to say: “The Army Field Manual on interrogation (Human Resource Exploitation Training Manual) was written at Fort Huachuca. A number of the officers and soldiers responsible for human rights abuses at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, and at Iraq's Abu Ghraib prison have worked at or were trained at the Headquarters for Army Intelligence Training at Ft. Huachuca.”

In his article he says that General Fast was the highest ranking intelligence officer tied to both Fort Huachuca and the torture at Abu Ghraib, along with couple of other soldiers out of 28 who were eventually implicated in the beating deaths of two prisoners in Afghanistan in 2002.

For some more background on Fort Huachuca, located 70 miles southeast of Tucson [home to the U.S. Army Intelligence Center and School (USAICS)], advocacy group Torture on Trial offers a brief summary of the history of complicity the base has served in the U.S.’s practice of torture. I won’t repost that here, but again, one gets the feeling all of this merely scratches the surface of the spatiality of torture today that is secretly distributed around the world in the context of the War on Terror.

[Image: Photo by Richard Ross in his amazing collection, Architecture of Authority

So, maybe Subtopia needs to invest in a heavy duty anti-torture chamber boring machine, and our own elite squad of photojournalists, geoscientists, engineers, landscape architects, and some very savvy local guides with a collective nose for sniffing out and exposing the subterranean troves of human rights violation and injustice. Using a modified supply of night-vision cameras, acoustic radar, seismic sensors, tunnel detection robots, and – above all, a crazy hyper-oxygenated toxic protective stealth capsule – just a little piece of mobile architecture specifically prototyped for our underground tube travels – this intrepid snoop troupe would mine below the cleverly disguised crusts of state secrecy to pave the way for yet another team of crepuscular spelunking tunnel rats, armed with customized ground penetrating radar headsets that have been meticulously calibrated to track down the distinctive vibrations of human screams buried far below the earth’s surface, that unmistakable jangle of rusted chain links, the buzzing of exposed electric cables – GPR capable even of identifying the thermal signatures of frying skin.

Drawn towards this gruesome atmosphere, the rat dudes find their way past the layered walls of the CIA’s black hole until suddenly they begin to pick up subtle melodic hints of what strangely sounds like a Britney Spears song. The terrestrial melody appears as an odd microgravity pattern on the team’s rigged void imager. Mineral samples from the structural formations insulating the void almost suggest a geologic barrier composed of some strange molecular sonic fortitude.

As they get closer the shape of a hollow cavity slowly emerges. However, with their advance they also become unordinarily nauseous – yet, like silent warriors they march. Sinking through the secret geography of galleys and shafts – and the architecture of their own extraordinary rendition program – they map a secret network of curvy passages and chambers; alas, the mysterious void has become incredibly clear. And, silly enough, as it turns out, this discovery actually looks a lot like the sexy body of some generic big booty pop star that’s been excavated and covered up and now appears in the palm of their hand on display; jokingly, it could easily be mistaken as a massive grave site for a giant sized Jennifer Lopez, or something.

Be that absurdly as it may, they drudge onwards with the taste of bile in their mouths towards what seems like a voluptuous underground nightclub now. How anticlimactic. With experimental endoscopic image and noise feeds they finger this great secret bod in the soil, surgically teasing evidence of its existence through tiny tubes – all broadcast on Subtopia, by the way – and eventually they realize they’ve tapped an entire infrastructure of torture hollows lurking several hundred meters below the tarmacs of an airport in Jordan; and then, almost moments later another one of our ragged teams finds something similar below a landing strip in Ireland; and again, beneath an old Soviet era compound in Romania and Poland, and on and on.

Subtopia has somehow managed to crack the equivalent of the War on Terror’s torture space mother lode! Quickly, a You Tube collection of diabolic sites are uncovered, but also the appendages that connect them; concrete arms, legs, blast protective breasts, all adapted out of old reused bunkers, storage depots, and war time tunnel systems through out Europe and Central Asia. And it’s all right here for your viewing pleasure.

Puking their brains out where no one could possibly hear them, our little tunnel rats find what they report as a vast piece of earth that’s been converted into an underground musical torture instrument. Cages and interrogation rooms reverberate with the throbbing beats of Brittney’s horrendous 2004 hit “Toxic.” And, sadly, tragically, finally arriving at the heartbeat of torture, hearing this loud and clear, our hidden crack crew goes violently awry, becoming so disoriented they completely lose control of their faculties, arriving so close to the soundtrack that their sensitive position is compromised. Trying to back out in a fit of panic, they cause the earth to cave in all around them. And just like that, in a flash the tunnel team is buried alive, entombed behind the CIA’s musically protected torture walls. Subtopia mourns the death of our heroes permanently resting in the rounds of Lopez’s concrete ass.

(Sorry for the stupid conclusion there, it's just thinking about this stuff too much takes a toll, and I had to entertain myself there for a second, or else I am buried by all of this. Blah blah blah!, once again....and for a related post: The Birth of the Red and White Pole.)