"Block D" Enters the Pantheon of GWOT Space

[Image: Pol-e-Charki Prison, Afghanistan.]

Thinking a bit more about the legacy of war measured in terms of the structural remains it leaves behind – maybe even through a specific material like concrete (as if the Bremer Wall were the architectural currency of the Global War on Terror) – not only has GWOT laid the foundations for its own inevitable fossilization with hundreds of miles of barricade (sharing an ironic resemblance to some sort of linear cemetery with a wall composed of thousands of tombstones), but this war is also expanding a whole other pantheon of spooky transient spaces that over time keeps emerging from these furtive corners of the world only to duck below the surface and reappear again at a later date, in some other squatting nomadic form. I guess the War on Terror leads one to wonder if it will even leave a visible footprint at all, say, a few hundred years from now. Furthermore, is that a good thing, or a bad thing? On one hand, if War can, in a sense, clean up after itself, then, hey, that’s something, right? Or, if it doesn’t’ actually do significant permanent damage or leave residue visibly on the landscape – you know, if no one is in the forest to hear a tree fall, then...? I mean, what if war became an exercise in green politics one day, what could that mean? But, what if all this really means is the urban body of this war is so traceless and ghostlike now that it has figured out a way to completely hide and dispose of its own evidence, its own inhumanity, criminality, so that there will be nothing left to analyze, to remember, to learn from in the future, to indict for war crimes?

[Image: Bagram Airbase, Afghanistan.]

Yes, a nebulous pantheon of war space: from suspect tent cities like the massive immigrant detention circus in Raymondville, Texas, “Camp Justice” at Guantánamo Bay, and the “The Rule of Law Complex” outside Baghdad, to the more clandestine chambers of the CIA’s extraordinary rendition torture taxi network and the ‘black sites’ of their secret prison archipelago, all the way to the hush-hush “Communications Management Unit” housed in the old death row facility at Terre Haute federal prison in Indiana, and the bureaucratic halls of the Pentagon where torture memos were passed along to the excessive legal verbiage that shields the state’s right to detain without charge, transfer without official notice, imprison without any fair trial. There’s even an entire floating world of prison hulks cropping up along our shores, full-on detention islands like Christmas Island and Diego Garcia, patrolled by alleged naval vessels like the Triton and the USS Bataan where refugees and terrorist suspects alike are scooped up and quietly made to disappear – the flip side of which are the laws that have been passed to allow these peripheralized expansions of national sovereignty to stretch well beyond their normal boundaries, to an indefinite suspension of refugee rights, and to legal mechanisms designed to deny asylum. Throw in other equally hidden architectures like the new underground bunker that was recently built below the capital building in Washington DC, or the tiny NSA spy room discovered nesting inside the AT&T building in San Francisco, and soon we see just how inbred and entrenched secret space is in the urban DNA of modern democracy.

Of course, more blatant and grim examples come to mind too, Abu Ghraib, the monstrous U.S. Embassy in Baghdad (which was just days ago declared ready for occupancy), the audacity of a foreign occupied Green Zone subject to constant attack, and even more mysterious places like the “top-secret” “Camp 7” at Guantánamo Bay. We can also hardly hesitate to include the growing atlas of border fences and security barriers that have turned up across every continent to further divide nations from themselves and refortify the hegemonic global cities of the world, while nearby contractor markets rake in billions in the management of detention facilities and interrogation housing units stashed in the structural folds of airports, shopping malls, train stations, and so on.

And we better not overlook the global portfolio of military real estate that would probably make Century 21 look like a dwarf mogul if we could accurately map and compare the two in sheer square mileage. More difficult to tour than an empire of bases and training camps, however, would be the much less formal territories of roving cars and disguised suicide bombers that lurk below the surface of the Middle East like a kind of unpredictable predacious root system; or the geospatial domains of ominous surveillance networks. For that matter, don’t forget the meticulously rendered virtual replicas of cities like Baghdad and Jerusalem that have been modeled and programmed down to the last crumbling alleyway all for the rehearsed fates of their military invasion.

And we can’t leave out the subterranean corridors of the Gaza smuggler tunnels, or the “apartheid urbanism” that continues to segregate the Palestinian community from the Jewish, above and below ground.

And the list goes on and on and on.

Even if we could calculate the cement tonnage of this footprint, I imagine an even larger volume of GWOT’s unholy vault could only be truly gaged by its cavities of architectural secrecy. But, how does one actually try to measure secret space? Our ally, Agent Plorver definitely has a unique approach combining geography and art as a hybrid form of landscape forensics, or something. Maybe our best tool is an experimental science of some kind, yielding geometries of spatial implication.

It’s like knocking on a hollow earth and studying the acoustic properties and vibration signatures of its reverberation. Maybe in this case, we are tracing hint of the political properties of secret space, tracking the legal patterns in their documented/censored jurisdictions, identifying signatures of spatial politics instead of subtle noise rhythms. Who knows?

[Image: NSA Spyroom in San Francisco / AT&T Whistle-Blower's Evidence.]

Certainly, the crypts of the War on Terror are as vastly hidden as they are maybe even obviously contained, vertical as they are horizontal, airborne as they are buried, private and concentrated perhaps as they are mainstream and diluted. I mean, it seems like some form of military space is present everywhere these days, permeating culture, the atmoshere like some groggy blanket of pollution. Are we secretly being haunted by a molecular and osmotic pantheon of war space looming over all our heads?

It swings inside the bowels of drones and unmarked Boeing jetliners from the stealthiest side of the spectrum all the way to an in-your-face side where shrapnel and body parts drape tragic streets only moments before gracing billions of television screens on the nightly news. As much as the War on Terror claims the rawest forms of built environment it is equally if not more so matched by a fetishized mediascape that plasters imagery of the War on Terror everywhere that it is not in existence already, while in between a range of mutant architecture manages to duck out of public view altogether; spaces of power, spaces of terrorism, spaces of subversion, spaces of torture, spaces of biopolitical arrest, dank walls, stark naked madness muddied by the perishing of our ideals. The walls between them are not always as distinguishable as we would like to think. As much as maybe we can approximate our observations of these spaces, situated in their own deviant archeology – their own "colonial present

I wonder, what will be left of the War on Terror a thousand years from now, what spatial shells might litter the earth, what geopolitical patterns of cracks will expose what we cannot see today of this extralegal landscape? I imagine measuring secret space then to be intimately connected with time and morphology.

But, if our observations of the politics surrounding and supporting this infrastructure of secrecy can help us to infer anything about the physical dimensions of secret space -- how it is politically created, articulated, hidden, how secrecy is politically encoded into space -- then maybe we can actually make some sorts of measurements today. And perhaps the opposite is also true – say we do manage to glimpse these discrete spaces, then what can we make of the fuzzy political logic, or spatial politics of the War on Terror?

Man, I wish I had more answers than I do just overworded and redundant questions.

As the landscape of war goes on unfolding I am totally intrigued by how space somehow resists exposure, and manages to squat in the hollows of abandoned buildings, inside deployable barracks, within the deeply buried lairs of marginalized insurgency, in the middle of American deserts, in the folds and atop the lofty cliffs of conflict’s various stages and vantage points. Architecture takes on the muted glint of obsidian secrecy slightly churning over in the rubble of an endless war's scarred battlefield.

The really scary thing to think about is all of the still yet undetected GWOT spaces there are to discover, to unearth, to vet in the light of legal question.

How can we better understand the physical and political connections binding these spaces – what Eyal Weizman calls a “Hollow Land

I’m particularly interested in space’s relation to the concept of terrorism as a cultural construct. That is to say, if we accept “the terrorist” as an embodiment of a westernized projection of fear, in part as a product of culture – the boogey man that has rallied the call to arms of colonialism for centuries, having always depended on the existence of an enemy for its own legitimization – then what does that suggest about ‘War on Terror space’ itself?

I’m hardly saying terrorism doesn’t exist, but only wish to explore how terrorism is also in part not only a colonial but an architectural phenomenon as well inextricably woven into our urban psyches, and how the spaces associated with terrorism politically help define, combat, and even fuel it; maybe the War on Terror is a strange kind of psychospatial pornographer, orchestrating these eerie scenes and stages for its own spectacular battles with terrorism, for whom we are all just insipid members of the audience trying to decipher a meaningless program.

Is space to some extent an unconscious collaborator in the psychic making of the west’s fear of terrorism? Of course it is.

I guess it all goes back to that same relationship: how our politics defines our spaces and how our spaces reinforce our politics; or, how the War on Terror produces space and how that space dictates the politics of the War on Terror. And of course, all of the psychology that is the interface between it all. Blah blah blah – blather you've heard from me before a million rhetorical times already.

[Image: Pol-e-Charki Prison, Afghanistan.]

Well, finally, without further rambling ado, we can now add a new space to this wicked pantheon. If you haven’t heard of it already, then let me present to you “Block D.” Or, “Block 4” as it is also apparently known: a newly built detention facility at the notorious Pol-e-Charki (or, Pul-i-Charkhi) prison just on the eastern outskirts of Kabul, in Afghanistan, quickly becoming understood as the Asian corollary of Guantánamo Bay. No matter, it is another utterly disturbing black hole in the universe of legally suspect and secret space.

In fact, as we hear more high profile urgings these days to close Guantánamo down finally once and for all, (or, at least for now), we learn that a sizable majority of the inmates held there have been from Afghanistan. Or, maybe you already knew that, too.

“Afghans were once the largest group of prisoners at Guantanamo, with over 200 Afghan men held there; now there are only about 34 left.”

And, while we may celebrate the fact that many of them are being released these days we quickly come to find that while they are being deported – not only back to Afghanistan – they are being taken directly to Block D, which was constructed specifically to contain the overflow of terrorist suspects from Guantánamo and the nearby Bagram American Airbase whose capacity has been pushed to its absolute limits. Essentially, the detainees are being relayed from one abysmal cage to another. Is that really any surprise though?

[Image: Pol-e-Charki Prison, Afghanistan.]

Pol-e-Charki prison, for those who aren’t familiar, has for decades been synonymous with torture and execution beginning in the ‘80’s during the Soviet era of communist rule, and more recently known for violent riots and dramatic hi-profile escapes by suspected Al-Qaeda or Taleban militants.

In 2006, hundreds of inmates, including convicted al-Qaida and Taliban militants, waving knives and wielding clubs made from furniture overpowered guards and took control of parts of a high-security prison. The prison holds 2,000 inmates, including some 350 al-Qaida and Taliban militants.You may also remember that a couple of years ago four al-Qaeda suspects escaped from U.S .custody at Bagram.

In December 2004, four inmates and four guards died during a 10-hour standoff that started when some al-Qaida militants used razors to wrest guns from guards and then tried to break out. Afghan troops stormed the prison and fired guns and rocket-propelled grenades to retake control. (source)

[Image: Al-Qaeda man's easy jail escape.]

If it’s true, as this article suggests, that the main reason for the detainee transfer is to help deflect some of the international criticism over Guantánamo Bay, then transferring them to a brand new facility at Pol-i-Charki seems hardly like a genuine gesture to allay the criticism.

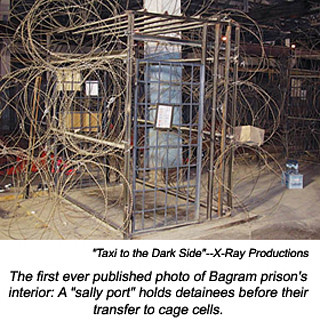

In the Washington Post’s early coverage of the CIA’s secret extraordinary rendition prisons, they tracked the development of the detainee population swell by writing “without a long-term solution, the CIA began sending suspects it captured in the first month or so after Sept. 11 to its longtime partners, the intelligence services of Egypt and Jordan.”

But not long thereafter, a month later in fact, according to the Post, the CIA soon found itself with hundreds of prisoners rounded up from the battlefields in Afghanistan on its hands, and with little means for holding them.

“A short-term solution was improvised. The agency shoved its highest-value prisoners into metal shipping containers set up on a corner of the Bagram Air Base, which was surrounded with a triple perimeter of concertina-wire fencing.Earlier this year, Joanne Mariner wrote a fantastic article exposing this. Having taken a couple of years to construct, and over a year to train Afghan guards, the U.S. government in 2007 opened Block D for business. “The new prison,” she wrote, “now known as the Afghan National Detention Facility (ANDF), is run by the Afghan government, at least in theory. But the U.S. paid for its construction (those who have been inside say it looks very much like a U.S. prison); the U.S. trained the guard staff (Afghan Ministry of Defense personnel), and the U.S. now claims to have a "mentoring" relationship with the Afghans who are in charge of it.”

[...] in the winter of 2001, that prisoners kept by allied Afghan generals in cargo containers had died of asphyxiation. The CIA asked Congress for, and was quickly granted, tens of millions of dollars to establish a larger, long-term system in Afghanistan, parts of which would be used for CIA prisoners.

The largest CIA prison in Afghanistan was code-named the Salt Pit. It was also the CIA's substation and was first housed in an old brick factory outside Kabul.

Salt Pit was protected by surveillance cameras and tough Afghan guards, but the road leading to it was not safe to travel and the jail was eventually moved inside Bagram Air Base. It has since been relocated off the base.” (source)

Since October 2006, the United States has transferred approximately 50 detainees out of Guantanamo to the custody of the Afghan government, part of a policy aimed at reducing the prison population and ultimately closing the facility. Once home, many of the Afghans have been left in a legal limbo not unlike the one they confronted while in U.S. custody.

For several years after the 2001 U.S.-led invasion of Afghanistan, detainees held at Guantanamo were set free once they returned to this country, due largely to its weak government and lack of infrastructure. But in 2005, American officials began negotiating an agreement that called for the U.S. government to provide Afghanistan with $20 million in aid to build Block D, train detention officials to run it, and develop a set of legal mechanisms. Since the invasion, the United States has pledged at least $160 million for judicial reform in Afghanistan, according to the State Department. (source)

If it looks like a rat, smells like a rat, tastes like a rat, then guess what?

[Image: Where the Detainees Have Been Held (NYT) / Foiling U.S. Plan, Prison Expands in Afghanistan.]

As of her article just this February, she reports that thirty-two Afghans have been transferred from Guantanamo to the ANDF, while at least 150 others have been passed on there from the U.S. detention camp at the nearby Bagram. Mariner asks a critical legal question, however: “With some 200 detainees having been formally transferred from US to Afghan custody in less than a year, the pressing question is this: What does this "mentoring" relationship mean?”

Does "mentoring" mean that once a prisoner enters the ANDF he is under the sole dominion and control of the Afghan government, and his fate is in Afghan hands? Or does it mean that the US transfers physical custody of the person, but still retains some control -- or authority, or influence -- over whether and when that person is released?Mariner also reminds us of the National Directorate of Security (NDS), “Afghanistan's notoriously vicious intelligence service” … writing that former NDS detainees “described being badly beaten, confined in small cages in basement jails, and hung upside down from metal hooks.” Sound familiar?

Continuing, she says “with a newly selected and trained guard force made up of military personnel, not NDS officers, the ANDF is not an NDS dungeon. Still, the question remains of whether it is, to some extent, a Guantánamo annex. Afghans who have been transferred from Guantánamo to the ANDF have said that American personnel are present and active in the facility.”

There have been some other great articles written on this recently, so allow me to post in bulk some key portions of those here. Eric Lewis reporting for Slate, says:

“The government claims that the prison is under the sovereign authority of Afghanistan and so lies outside U.S command—and beyond the reach of our courts. Yet these prisoners are being held in a special "national defense" wing built by our government and staffed by American jailers and interrogators. The Policharki transfers are the latest example of the Bush administration's long-running effort to evade judicial review of the thousands of detentions that have resulted from the war on terror.”He then proceeds to brief us not only on the gruesome history of the Pol-i-Chakri prison and its torturous past, but describes the conditions at Bagram as being even worse than those at Guantánamo. “The U.S. government has conceded that it does not have the resources to determine in a timely way whether individual detainees are being properly held. And Bagram lacks even the unsatisfactory Combatant Status Review Tribunals used at Guantánamo.”

Lewis tells us that “Determinations of combatant status are not made through any evidentiary hearing, but rather by the commanding officer at Bagram, who has discretion whether to gather evidence, hear witnesses, or allow the detainee to present his story. […] Given these conditions, the U.S. authorities are concerned that the Supreme Court's decisions granting detainees some rights to challenge their confinement at Guantánamo could spell legal trouble at Bagram.”

And therein lies the juice: in order to prevent detainees from having access to future rights Block D has been constructed to further file them away in the corridors of the great legal abyss. “No Afghan court appears to have jurisdiction over Policharki's national defense wing," he writes. "Nor have basic rights in Afghan law been afforded to the detainees there. Like our Constitution, the Afghan Constitution provides a right to counsel from the time of arrest, yet to date no Afghan detainee at Policharki has been permitted to see a lawyer, despite requests by family members and Afghan human rights groups.” (source)

[Image: "Afghan men in Kabul in February after they were freed from the United States prison at Bagram." Syed Jan Sabawoon/European Pressphoto Agency (NYT) / Foiling U.S. Plan, Prison Expands in Afghanistan.]

There was even more recently an excellent piece in the New York Times on this written by Tim Golden who deconstructs the political disputes between U.S. and Afghan officials (and even more intriguing within the Afghan government itself) over the terms of development for the new facility, and how it would legally be constituted according to whose model, and overseen by which government.

In a confidential diplomatic agreement in August 2005, a draft of which was obtained by the New York Times, the Bush administration said it would transfer the detainees if the Kabul government gave written assurances that it would treat the detainees humanely and abide by elaborate security conditions. As part of the accord, the United States said it would finance the rebuilding of an Afghan prison block and help equip and train an Afghan guard force.While Golden’s article also gets into the horrendous conditions at The Bagram Theater Internment Facility, as it is called, and ultimately how it has expanded as to receive the overflow of terrorist suspects rounded up by the U.S. all over the world, he discusses how Afghan officials had rejected pressure from Washington “to adopt a detention system modeled on the Bush administration’s “enemy combatant” legal framework,” and mentions that there were some Defense Department officials who had “even urged the Afghan military to set up military commissions like those at Guantánamo.”

Yet even before the construction began in early 2006, the creation of the new Afghan National Detention Center was complicated by turf battles among Afghan government ministries, some of which resisted the American strategy, officials of both countries said.

A push by some Defense Department officials to have Kabul authorize the indefinite military detention of “enemy combatants” — adopting a legal framework like that of Guantánamo — foundered in 2006 when aides to President Hamid Karzai persuaded him not to sign a decree that had been written with American help.

Then, last May, the transfer plan was disrupted again when the two American servicemen overseeing the project were shot to death by a man suspected of being a Taliban militant who had infiltrated the guard force.

Afghan officials rejected pressure from Washington to adopt a detention system modeled on the Bush administration’s “enemy combatant” legal framework, American officials said. Some Defense Department officials even urged the Afghan military to set up military commissions like those at Guantánamo, the officials said.I guess it is still largely and conveniently unclear as to what exact legal framework really governs Block D. In the rest of Golden’s , which I urge you to go read for yourself, he breaks down how the design of the wing has turned out to be a major flop due to various factors, like religion and how the detainees might (or might not) be able to share cells and bathrooms, and how the Afghan guards would or would not be able to manage high profile detainees. The gist, is that the estimated design called for a total capacity of 670 prisoners, but eventually was cut in half later by design decisions, which means more detainees will remain at Bagram. Is that a good thing, I don’t know. The conditions there from what I can tell are worse than anywhere else, yet, since it is an American base is there still hope that those detainees there may one day receive more legal recourse than those lost to the new Block D?

Officials of both countries said the defense minister, Abdul Rahim Wardak, was reluctant to take responsibility for the new detention center as the Pentagon wanted, fearing he would be besieged by tribal leaders trying to secure the release of captives. The minister of justice, Sarwar Danish, opposed sharing his control over prisons, the officials said.

American officials finally brokered an agreement between the ministries, internal documents show. But that did not resolve more basic questions about the legal basis under which Afghanistan would hold the detainees.

For nearly a year, American military officials and diplomats worked with the Afghan government to draft a plan for how it would detain and prosecute all prisoners captured in Afghanistan. Colonel Supervielle, who had helped set up legal operations at Guantánamo, said the effort in Afghanistan was in some ways more complex. “You weren’t dealing just with a U.S. interagency process,” he said. “It involved the interagency process, bilateral relations with Afghanistan, the military coalition and other international interests.”

The draft law was finally delivered to Mr. Karzai in August 2006. Despite American entreaties, he decided not to sign it after opposition from senior aides, officials said.

Finally, not long ago Human Rights First delivered a report on the U.S.’s involvement (or lack of involvement, as the case may be) in the kinds of court proceedings taking place for detainees in Afghanistan after being transferred from Guantánamo and Bagram.

"The United States has turned over the prosecution of Afghan Bagram and Guantánamo detainees to the Afghan criminal courts, but has consistently failed to provide sufficient evidence to support the allegations of criminal activity necessary for fair trials, said " Sahr MuhammedAlly, the report’s author and a senior associate in Human Rights First’s Law and Security program.More to come, of course, as I come across it. But, let’s not let Gitmo get all the fame and fortune, there are other equally if not more deserving architectural candidates for the worst place on earth to be as a GWOT detainee, and with all the ruckus over the Cuban-based detention center, it kind of makes one wonder if it isn’t making now for the perfect distraction tactic from noticing the other equally if not even more real and heinous detention camps doing the dirty job of torture elsewhere where the public is hardly aware.

The so-called "evidence" being used to prosecute the repatriated detainees violates international fair trial standards and, in many cases, Afghan law, the report finds. The U.S. government provides the Afghans with "highly general" declassified versions of the Detainee Assessment Branch Reports of Investigation (ROIs), which form the basis of the Afghan charges. Typically, these ROIs state the date of capture, the capturing force and what the detainee was alleged to have done. Absent, however, is real evidence, such as the names of individual witnesses or statements in the court dossier—sworn or unsworn—of any U.S. soldiers or officials involved in the capture or interrogation of the detainee.

In the trials witnessed by Human Rights First, and in all of these trials, according to defense lawyers interviewed by Human Rights First, there are no prosecution witnesses called to testify or even sworn witness statements submitted by the prosecution, and there is little or no physical evidence. The trials are conducted based on the in-court reading of investigative summaries prepared by U.S. and Afghan officials which purportedly support the allegations. “These no-witness, little to no evidence, paper trials deny the defendant the fundamental fair trial right to challenge the evidence and mount a defense,” said MuhammedAlly.

More than 160 Block D cases have been referred for prosecution thus far, while the charges against the rest have not yet been finalized. Charges under Afghan law range from the destruction of government property to treason and threatening the security of Afghanistan. Trials last from 30 minutes to an hour, according to personal observations of trials cited in the report and in-person interviews with Afghan officials and defense lawyers involved in these trials. Since the trials began in October 2007, 65 former U.S. detainees have been convicted and sentenced to either time-served or imprisonment ranging from 3 to 20 years, while 17 have been acquitted.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home