The investigations of geographer and writer

Stephen Graham show us a city not only caught in the crosshairs of a perpetual war between international military coalitions and their swarming counterparts, but a city that’s been reframed, re-imaged, as a strategic site in a larger

geo-economic scheme for engineering the urban machinations of control that are necessary to secure the triumph of neoliberal capitalism across the globe.

Absolutely critical research, as far as I am concerned.

Back in

April, just a few months after

Subtopia launched and began to pick up steam, Steve and I quickly made contact at which time he told me he was working on a new book titled

Cities Under Siege: the “new” military urbanism.

Needless to say, I was sold on the title alone, but as a prelude, I read a brilliant book he edited a couple of years ago –

Cities, War, and Terrorism – and was blown away by its framework for observing modern conflict in the context of urbanization, and how frictions in global politics are turning cities into stages for warfare and geopolitical struggle –

towards an urban geopolitics as he aptly subtitled the book. It’s a seminal read for anyone interested in conflict as a kind of spatial system.

Of a handful of people we might consider to be the true thinkers around a military urbanism Steve is certainly one of the most important. With a dual background in urban technology and city planning his range of research is diverse and daring, utterly contemporary, and he has a fierce list of publications deconstructing the hyper-landscape of this subject – a great inspiration for our endeavors here, to be sure.

So, continuing my conversation with bad-ass geographers and picking up perhaps where

Neil Smith and I left off, Steve and I shared this exchange over the last few weeks. This is the first of two parts that explores a spectrum of militarization and the nature of urban space as a product of war and political violence. He also traces for us some of the evolution of this “new” military urbanism that he's developing further in his book

Cities Under Siege due out sometime next year.

I have to say I am really psyched about this and want to thank Steve again for having taken such time and for all his continued support of

Subtopia.

• • •[Bryan Finoki]

• • •[Bryan Finoki] To begin, I am wondering how you conceptualize the Global City and its military role in expanding global capital. I am also interested in the opposite notion, of how cities can be inherently resistant to imperialism rather than acting as mere pistons for the expansion of capitalist development.

[Stephen Graham] Global cities, as the key nodes in the transnational architectures of neoliberal capitalism, are vitally important militarily. They organize the financialization and production of space (London, for example, basically controls the financial architectures of large swathes of Africa and the Middle East). They orchestrate the extending dominance of neoliberalism. They serve as key hubs in the lacing of the world through transnational control, transport and logistics infrastructures. And, they are of course preeminent symbolic spaces for transnational capitalism, making them vulnerable as symbolic targets.

But, as you say, global cities, like all cities, are porous and mixed up spaces, and amount to an infinite variety of space-times way beyond those of the financial core, the logistics function, or the power of the state. The diasporic communities and social movements that are most actively contesting neoliberal capitalism all work through, and within, what geographer

Peter Taylor has called, the ‘World City Network.” This is the idea that it is an integrated network of world or global cities that together orchestrates the geographies and political economies of neoliberal capitalism (see

GaWC: Globalization and World Cities).

[Bryan Finoki] And, of course, with a network of global cities comes a corresponding expansion of militarism. Much of your work deconstructs the ways and processes that militarism has become increasingly blurred in the heightened security of the western city. How does this domestic militarization of space mirror that occurring in the bombastic urban sprawl of the underdeveloped world? Aren’t both of these geographies exhibiting more and more similar urban complexions that would suggest no place in this century is exempt from being readied for war?

[Stephen Graham] I think so. The global mixing in today’s world renders any simple dualism between North and South, or Developed and Developing, very unhelpful. Instead, it’s more useful to think of transnational architectures of control, wealth and power, as passing through and inhabiting all of these zones but in a wide variety of ways. Extreme poverty exists in many ‘developed cities’ while enclaves of supermodern and high-tech wealth pepper the cities on South East, Southern and Eastern Asia.

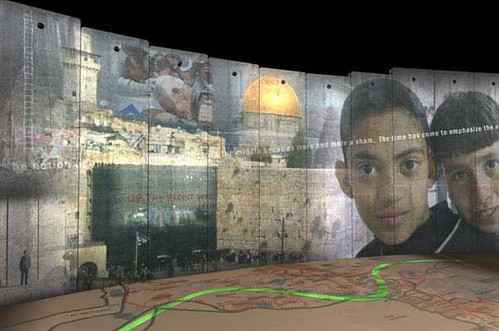

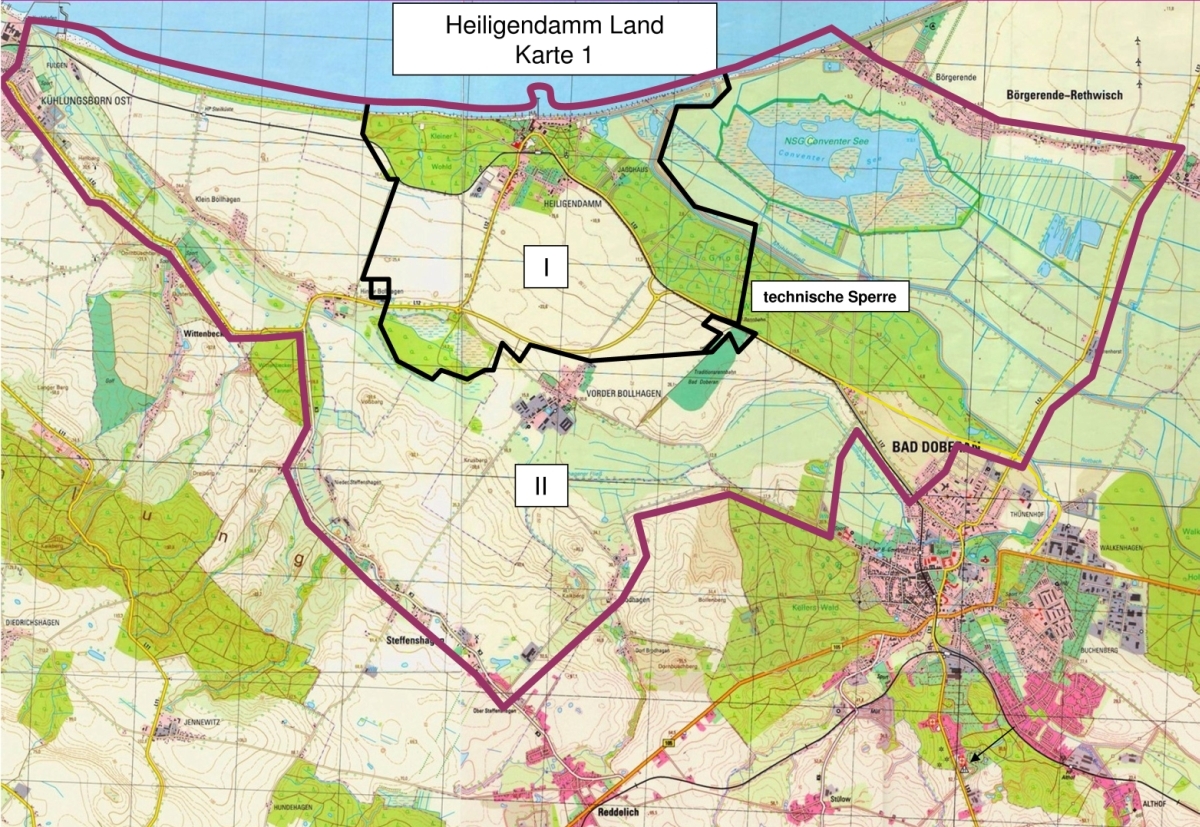

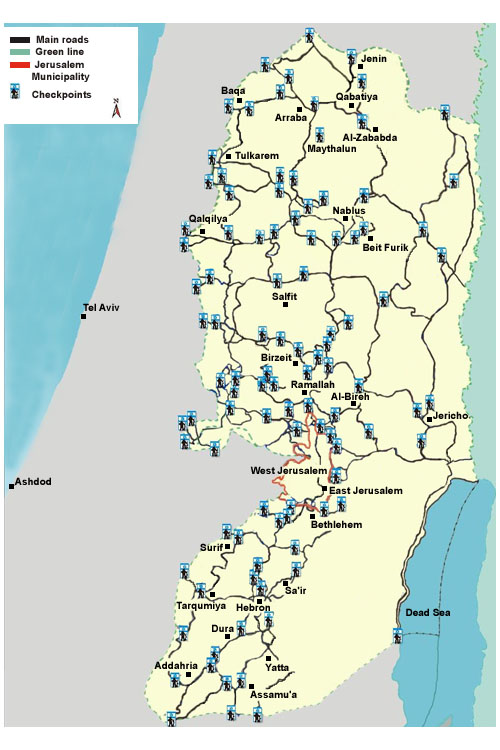

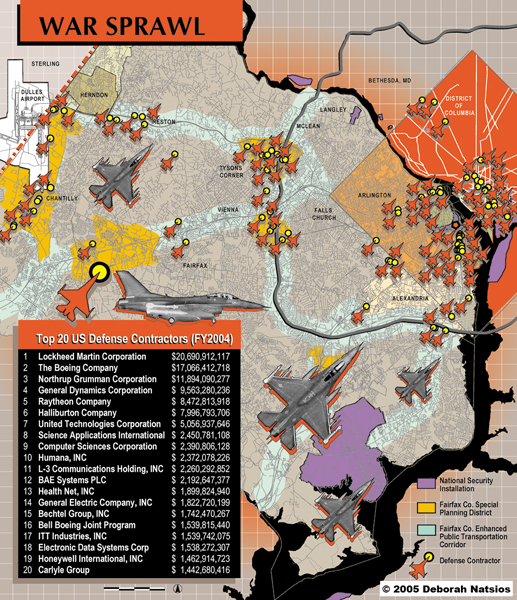

[Image: A map of IDF checkpoints that extend a matrix of control through out the West Bank.]

[Image: A map of IDF checkpoints that extend a matrix of control through out the West Bank.]Militarised geographies of (attempted) control are fully inscribed into the construction, maintenance and extension of these archipelago geographies. Take, for example, the militarized borders and surveillance systems which organize the relationship between foreign, ‘free’ trade and export processing zones and the ‘outside’. Or the relationship between gated communities, privatized public plazas, ‘security’ zones or airports, and the ‘normal city ‘outside’. In all these cases we see the emergence of new urban borders where control architectures and technologies are used to try and force the flows of the city through ‘obligatory passage points’ where they can be scrutinized and, if possible, identified.

[Bryan Finoki] Even though perhaps these ‘obligatory passage points’ have always been a part of capital’s fabric and are now just fulfilling their role at a time of hyper-urbanization and migration through an embedded pattern of urban bordering, I feel like we have entered

the age of the checkpoint, both symbolically with the mechanisms monitoring the global flows of capital but also literally with the proliferation of military checkpoints.

Which sort of leads me to my next question: I’m fascinated by how your work traces a spatial narrative of conflict and the morphology of the city as a kind of fossilization of political violence over time. Could you enlighten us with a brief history of the city in the context of violence?

[Stephen Graham] The histories of the city and of political violence are, of course, inseparably linked. As

Lewis Mumford teaches us, security is, of course, one of the very reasons for the very origins of urbanization. The evolution of urban morphology, as you say, is closely connected to the evolution of the geographies and technologies of war and political violence: fortification and the bounding of urban space through defensive and aggressive architecture are especially central to this long and complex story. So, too, is the fortification of cities to the symbolic demonstration of wealth, power and aggression, and as the commercial demarcation of territorialities. The elaborate histories of siege craft, atrocity, the symbolic sacking and erasure of urban space, and cat and mouse interplay of tactics and strategies of attack and tactics and strategies of defence, are all central here. Much of the

Old Testament, in fact, is made up of fables of attempted and successful urban annihilation. As

Marshall Berman has argued, “Myths of urban ruin grow at our culture’s root.” Important, here, are the symbolic roles of urban sites as icons of victory, domination and political or religious regime change.

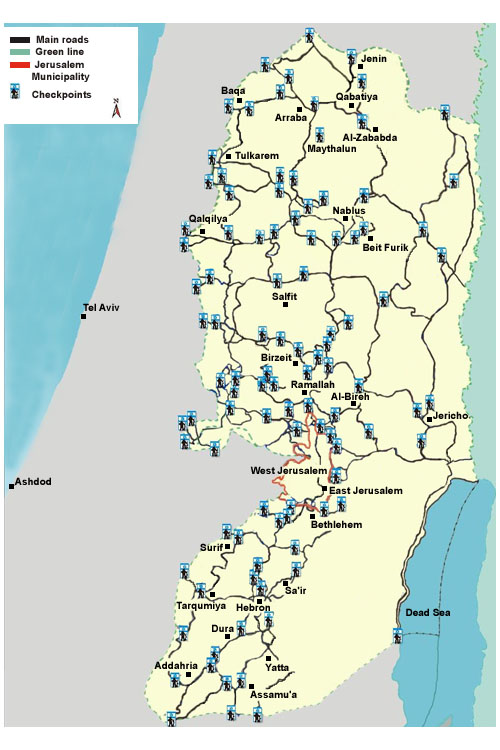

[Image: The remains of Cologne, Germany, the heart of Rhineland, after the bombing during WWII.]

[Image: The remains of Cologne, Germany, the heart of Rhineland, after the bombing during WWII.]All of this is fairly obvious. What fascinates me is that the histories of modern and late capitalist urban development tend to retreat from and obfuscate the continued centrality of cities as strategic sites within war and political violence. The obvious, physical, architectures of fortification have clearly left the city as it becomes ‘over-exposed’ – in

Virilio’s terms – to the new optics and technics of transnational and Total War. Remaining fortifications, at that point, are reinscribed as tourist sites: reminders of a simple relationship between architecture and violence. And – at least until recently – nation states have clearly worked to construct and maintain their monopolies on political violence in a way that rendered cities as mere targets. This reached its apogee within the Cold War imaginaries of full scale nuclear Armageddon.

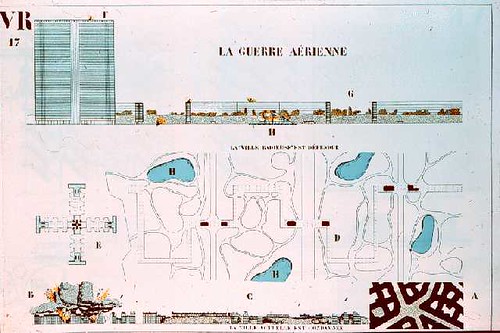

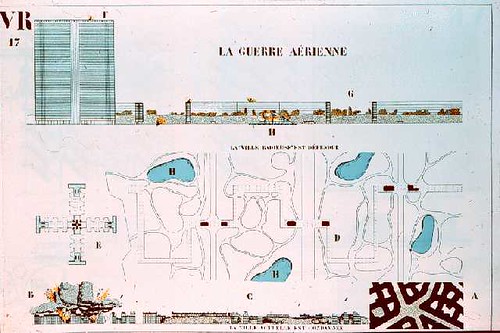

Partly because of these changes, the more stealthy and subtle relationships between modern urbanism and war, when discussed at all, now lurk more in the interstices of urban debate. Who recalls the obsession of

CIAM and Le Corbusier’s

‘Ville Radieuse’ with building ‘towers in the park’ not just as generators of a new machinic urbanism, or of the interplay of light and air, but as buildings that were both difficult to hit through aerial bombing and which would raise their inhabitants up above expected aerial gas attacks? Who remembers the role of nuclear paranoia in adding further momentum to the racialised politics of

‘White Flight’ in the USA during the 1950s? And who, in their architecture or planning training, are treated to courses on the roles of these disciplines as engines of destruction, annihilation, and politicised violence against those people and places deemed to be anti-modern, backward, unclean, or dangerous to the state, or the fetishised image of the emergent ‘global’ city?

These obfuscations mean that architecture and critical urbanism remain ill-equipped to deal with the way in which war and political violence are re-entering the city in the post Cold War world.

[Image: This is a cross-section of La Ville Radieuse by Le Corbusier, one of his schemes for an Ideal City.][Bryan Finoki]

[Image: This is a cross-section of La Ville Radieuse by Le Corbusier, one of his schemes for an Ideal City.][Bryan Finoki] Is it a general lack of awareness in academia and other fields of urban practice that prevents understanding these very types of repercussions inherent within the practice of the built environment? Or, is it emblematic of a deeper pervasive ignorance amongst architects and planners that don’t care to understand how the intrinsic political nature of their work may serve to hasten the racialization of the landscape, or the negative pathological effects of frenzied securitization? I mean, is it just a blatant refusal on the part of urban practitioners today to have a political conscience?

[Stephen Graham] Architects and planners are often still wedded to a heroic and positive self-image where their efforts necessarily work to render the world a better place. Construction and regeneration are the watch words: the inevitable destruction, erasure and political violence involved are obfuscated or taboo. This is linked to a poor understanding of the politics of urban space and their roles within projects of militarism and political violence.

Critical theorists

Ryan Bishop and

Gregory Clancey (2002, 64), recently suggested that modern urban social science in general has shown marked tendencies since World War II to directly avoid tropes of catastrophism (especially in the west). They argue that this is because the complete annihilation of urban places conflicted with its underlying, enlightenment-tinged notions of progress, order and modernisation. In the post-war, Cold War, period, especially, “The City”, they write, had a “heroic status in both capitalist and socialist storytelling” (66). This worked against an analysis of the city as a scene of catastrophic death. “The city-as-target” remained, therefore, “a reading long buried under layers of academic Modernism” (ibid. 67).

[Image: The Atomic Bombardment of New York, a painting by Chesley Bonestell.]

[Image: The Atomic Bombardment of New York, a painting by Chesley Bonestell.]Bishop and Clancey also believe that this “absence of death within The City also reflected the larger economy of death within the academy: its studied absence from some disciplines [urban social science] and compensatory over-compensation in others [history]” (ibid.). In disciplinary terms, the result of this was that the ‘urban’ tended to remain hermetically separated from the ‘strategic’. ‘Military’ issues were carefully demarcated from ‘civil’ ones. And the overwhelmingly ‘local’ concerns of modern urban social science were kept rigidly apart from (inter)national ones. This left urban social science to address the local, civil, and domestic rather than the (inter)national, the military or the strategic. Such concerns were the preserve of history, as well as the fast-emerging disciplines of international politics and international relations. In the dominant hubs of English-speaking urban social science – North America and the UK -- these two intellectual worlds virtually never crossed, separated as they were by disciplinary boundaries, scalar orientations, and theoretical traditions. (see Bishop, R. and Clancey, G. (2003),

“The city as target, or perpetuation and death”. In R. Bishop, J. Phillips and W.W. Yeo (eds.), Postcolonial Urbanism, New York : Routledge, 63-86.)

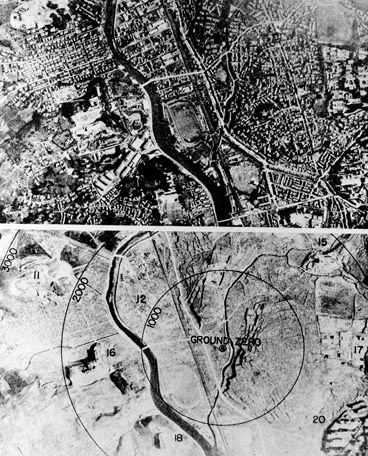

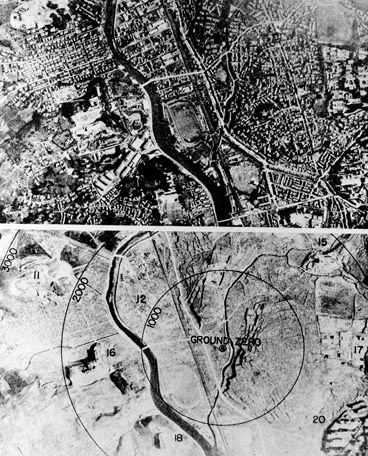

[Image: Ground view of Nagasaki before and after the bombing; 1,000 foot circles are shown. (Photo from U.S. National Archives, RG 77-MDH).][Bryan Finoki]

[Image: Ground view of Nagasaki before and after the bombing; 1,000 foot circles are shown. (Photo from U.S. National Archives, RG 77-MDH).][Bryan Finoki] Also, it seems the military itself is the quickest to make use of the connections between war and space, or even architectural theory, not only as a means for better strategizing their campaigns of urbicide and creative destruction, but perhaps also as a way to gain further legitimacy to their planning – hijacking the discourse of architectural urban theory to bolster the technical approvals of their surgical destruction of the built environment, no?

[Stephen Graham] Whilst Israeli military theorists have appropriated

Deleuze and Guattari (see

Eyal Weizman’s new book

Hollow Land), most of the US military material about cities looks more like a high school urban geography class. (Even in Israel, this approach is now out of favour).

The level of debate here is very simplistic and recycles old stereotypes from Orientalist urban books like Spiro Kostof’s

‘City assembled’ (eg. Islamic cities have no real structure etc.). As far as I can see, there is a strong disconnect between the more theoretical treatments of military transformation and the challenges of ‘urban operations’.

[Bryan Finoki]

[Bryan Finoki] Is the type of defensive urbanism we see today that attempts to bomb proof our skyscrapers and wall off different enclaves in Baghdad, merely a new iteration of an ancient strategy to fortify sovereignty – a postmodern medievalism, if you will – or, have we reached a completely new definition of ‘military urbanism’?

How do you distinguish ‘military urbanism’ from the “new” ‘military urbanism’?

[Stephen Graham] The ‘postmodern medievalism’ is a fascinating argument, I think. There is certainly a sense amongst military theorists of scrambling to look back at the proxy urban wars of colonialism – and elsewhere – to learn lessons that might help inform tactics in places like Baghdad.

However, I don’t think we really are going ‘back to the future’ in some simplistic way. Rather, political violence and war are being re-inscribed into the micro-geographies and architectures of cities in ways that, whilst superficially similar to historic defensive urbanism, inevitably reflect contemporary conditions. Important here, at the very least, are some important distinctions:

• The constant real-time transmission of video, images and text via TV and the ‘Net;

• The increasingly seamless merging between security, corrections, surveillance, military and entertainment industries who work continually to supply, generate, fetishise, and profit from urban targeting, war and securitisation;

• A proliferating range of private, public and private-public bodies legitimised to act violently on behalf of capital, the state, or ‘the international system’;

• The mass and repeated simulacral participation of citizens within spaces of digitised war, especially Orientalised video games produced by the military;

• The particular vulnerabilities of contemporary capitalist cities to the disruption or appropriation of the technical systems on which urban life relies. (These are caused by the proliferation, extension and acceleration of all manner of mobilities, the tight space-time coupling of the technical infrastructural flows that sustain ‘globalization’, and, more prosaically, the fact that modern urbanites have few if any alternatives when the fuel stops, the electricity is down, the water ceases, or the food and communication stops; or the waste is not removed);

• The ways in which borders and bordering technologies are emerging as global assemblages continually linking sensors, databases, defensive and security architectures and the scanning of bodies;

• The centrality of urbicidal violence or neglect to the new geographies of ‘primitive accumulation’ through which private military corporations and ‘reconstruction coalitions’ produce, and benefit from, what ‘disaster capitalism’ (Naomi Klein’s term) or “accumulation by dispossession” (David Harvey’s phrase) – whether in Baghdad or New Orleans; and

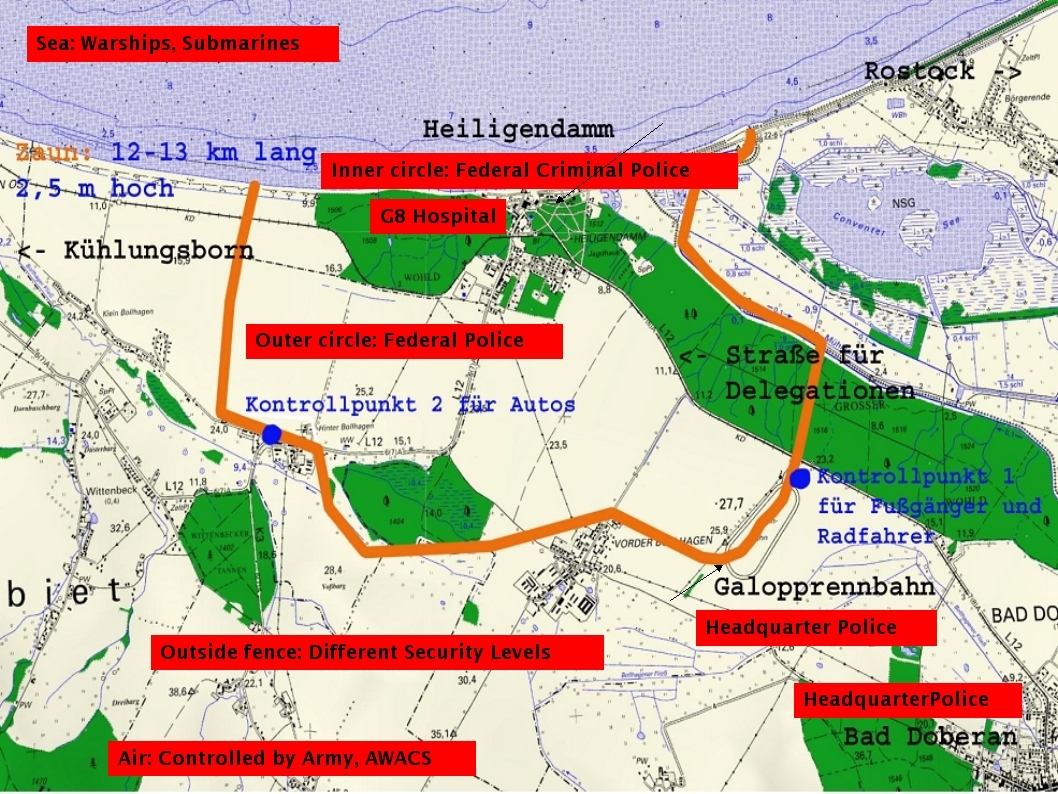

• The growing importance of roaming circuits of temporary securitised zones, set up and policed by cosmopolitan roaming armies of specialists, to encompass G8 summits, Olympics, World Cups, etc.

Added to this, we have new relationships emerging in the long-standing interplay of social and urban control experiments practiced on the populations of colonised cities and lands, and appropriated back by States and elites to develop architectures of control in the cities at the “heart of empire.” Thus, biometric borders emerge around Fallujah before being inscribed into the world’s airline systems. The complex legal and architectural geographies of extra-territoriality, permanent exception, and privatised political violence are set out through the global system of establishing and securitizing off-shore trading and manufacturing enclaves before being implanted into the Palestine territories of the “war on terror’s” “archipelago of enclaves.” Israeli practice of ‘shoot on sight’ is directly imitated, following advice from the IDF, by UK counter-terrorist operations on the London tube after 7/7. And the Pentagon’s experiments in the tracking of entire urban traffic systems provide an input into the shift to ‘smart’ or ‘algorithmic’ CCTV in western cities.

All these connections, of course, are lubricated by the fact that it is the same corporate bodies that are driving forward both the new strategies of urban warfare in the Middle East and the ‘surveillance surge’ as part of the Homeland Security’s drive in the global North.

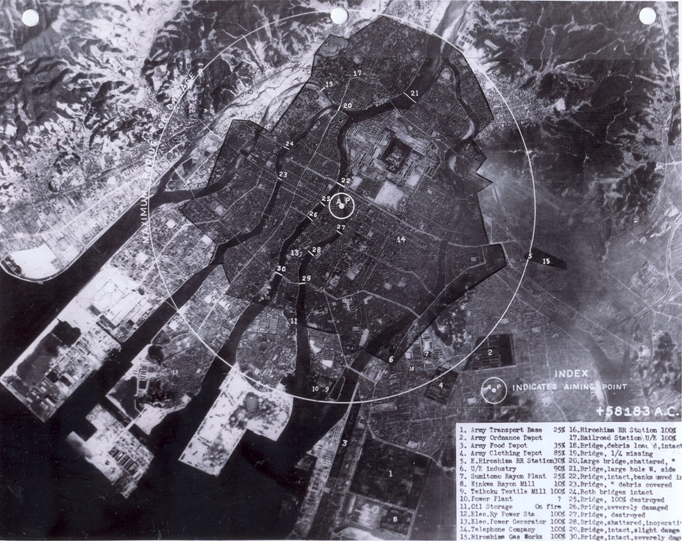

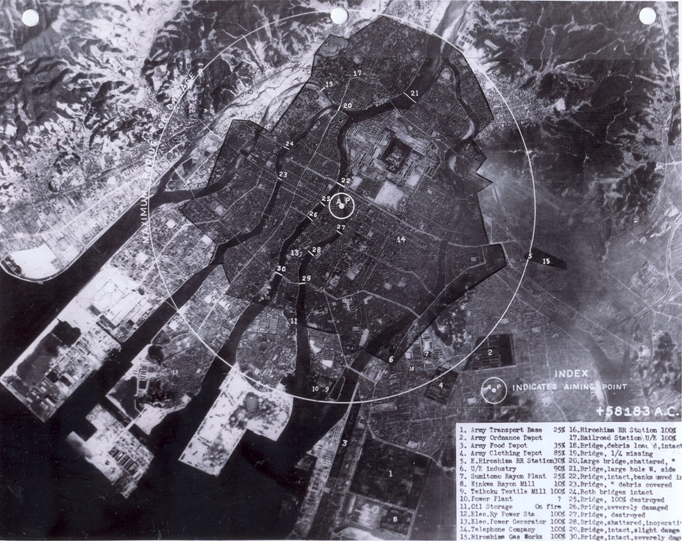

[Image: A photo prepared by U.S. Air Intelligence for analytical work on destructiveness of atomic weapons. The total area devastated by the atomic strike on Hiroshima is shown in the darkened area (within the circle) of the photo. The numbered items are military and industrial installations with the percentages of total destruction. (Photo from U.S. National Archives, RG 77-AEC).][Bryan Finoki]

[Image: A photo prepared by U.S. Air Intelligence for analytical work on destructiveness of atomic weapons. The total area devastated by the atomic strike on Hiroshima is shown in the darkened area (within the circle) of the photo. The numbered items are military and industrial installations with the percentages of total destruction. (Photo from U.S. National Archives, RG 77-AEC).][Bryan Finoki] And I think that gets at the biggest important distinction between then and now. That is, the sheer capitalist industrial-complex nature of the defense economy that doesn’t just fortify the city to protect it from violence and war, but the global scale arming of nations and geo-economic restructuring of conflict zones that insure conflict will always exist, in order to profit off of the modern defensive measures that go into regulating these conflict zones. What do you think?

[Stephen Graham] I completely agree: these complexes don’t just celebrate and fetishise war and wholesale securitisation -- they need it. The deepening cross-overs between war industries and policing, event management, border control, urban security and entertainment work to permeate and normalize cultures of war and militarism in a way where traditional separations between the ‘inside’ of nations and the ‘outside’ increasingly fall away.

[Bryan Finoki] I know you have a new book you are working on (or a couple of new books actually), one of which is entitled

Cities Under Siege. Could you tell us about that and how it departs from your previous work in your book

Cities, War, and Terrorism?

[Stephen Graham] Cities Under Siege: The New Military Urbanism will be a sole-authored book, published through a non-academic press (

Verso), rather than, as with

Cities, War, and Terrorism, an edited, academic text. I hope, therefore, to make it more coherent and accessible to the proverbial ‘lay’ audience that

Verso can reach.

The book aims to expose the complex processes and politics through which western military doctrine is increasingly preoccupied with the micro-geographies, architectures and cultures of urban sites. In this sense, it is a further attempt in my effort to develop an explicitly urban rendition of critical geopolitical analysis that commenced within

Cities, War, and Terrorism.

[Image: Israel hollows Lebanon with bombs in 2006.]

[Image: Israel hollows Lebanon with bombs in 2006.]The main body of

Cities Under Siege will raise a key set of dimensions to the urban ‘turn’ within western military doctrine, thinking and practice. It will address the powerful anti-urban imaginative geographies which tend to essentialize cities as Hobbesian sites of decay, hyper-violence and threats to political establishments. The book will also link this to a discussion of how ideologies of ‘battlespace’ within contemporary military doctrine -- whether it be the

‘Revolution in Military Affairs’ (RMA), ‘asymmetric warfare’, the ideas of ‘effects-based operations’ and ‘fourth generation warfare’, or, the Pentagon’s new obsession with the ‘Long war’ – which essentially amounts to the rendering of all terrain as a persistently militarised zone without limits of time and space. The other five chapters in the book will explore:

• The technophiliac dreams of omniscience and total surveillance that are so powerful within U.S. military discourse about cities;

• The ways in which state militaries like the U.S. and Israel routinely target essential urban infrastructures;

• The role of digital play and physical urban simulation within the ‘media-industrial-military-entertainment’ network;

• The importance of fantasies of erasing particular places through urbicidal warfare’, and

• The relationship between war and the increasingly militarised design and semiotics of automobiles.

[Bryan Finoki] Wow, that sounds fascinating. What can I say, I can’t wait. I’m reminded of the work of Philipp Misselwitz and Tim Rieniets who describe in a recent book

‘City of Collision’ a

‘conflict urbanism’ as a diagnosis of Jerusalem and the types of flexible spatial configurations that have produced, in their words, “a city in a permanent state of destruction and reinvention, hostage to political planning, collective fear and physical and mental walls.” But, clearly this speaks more widely about the urban transformations that are happening in regions all over (as it sounds like

Cities Under Siege also gets at) including the capitalist sanctums of the Northern hemisphere.

How has the military always exercised both a direct and indirect role in the urban design of cities? How can we gage the relationship between urban planners and military strategists today in the transformation of the contemporary western city?

[Stephen Graham] The Israeli experience, in terms of reorganizing the architectures of control in the colonised West Bank, launching permanent and’ preemptive’ military strikes against Palestinian and other cities, and in the intense securitizing of it’s own cities, is clearly the paradigmatic case of contemporary military urbanism. So, the constantly morphing geographies of Jerusalem, Gaza and the West Bank, as important studies by people like Eyal Weizman, Philipp Misselwitz and Tim Rieniets and have demonstrated, are vitally important.

But these cases are much more than mere paradigmatic examples: they are exemplars that are being actively imitated and exported around the world. To a large degree, Israel’s economy is now a service-security economy which relies very much on selling its products, weapons and what we might call ‘military urbanism services’ to all comers. The shooting of the Brazilian,

Jean Charles de Menezes, on the London Underground on July 22nd, 2005, was the result of a direct imitation of Israeli ‘shoot to kill’ policy against suspected suicide bombers. The U.S.’s use of biometric borders, targeted assassinations, and D9 caterpillar bulldozers in Iraq were all directly brought in from Israel. And U.S. forces are working very closely with the Israeli military in undertaking their own urban warfare and training doctrine.

Regarding the military in exercising a direct or indirect role in the urban design of cities, the role has more often been indirect than direct. But a key trend now is for the U.S. military to become much more actively involved within ‘urban operations’ in U.S. cities, a trend which undermines the rulings of the

Posse Comitatus Act of 1878, which was designed to inhibit military operations within the continental USA. Now, U.S. forces have a strategic command for North America (Northcom). They regularly undertake urban warfare exercises and simulations in real U.S. cities, and they are increasingly blurring with the more militarized ends of the law enforcement agencies, creating a military-civil continuum rather than a binary separation. It is this continuum that directs the shaping of security zones, new checkpoints, and other defensive architectures in U.S. cities, along with major inputs from building regulation changes. This is happening along with important participation from architects, landscape architects, geographers, planners and urban designers on the contemporary challenges of urban securitisation. Added to this, though, are major coalitions of commercial actors such as insurance, real estate bodies, and what the ACLU has called the

"Surveillance Industrial Complex." Also involved are transnational players like the organisers of major sporting events and political meetings who are keen to use each event as roaming experiments in state-of-the-art urban securitisation.

[Bryan Finoki] In a previous article of yours,

From Space to Street Corners: Global South Cities and US Military Technophilia, you talk about how western post Cold War military analysis has depicted the processes of urbanization in the global south as “essentialized spaces” which are meant to undermine the high-technology of U.S. military power. Partially because western strategists had neglected urban warfare through out the Cold War in favor of a heavy reliance on the Air Force which had to essentialize another projection about ‘enemy space’, where cities weren’t battlefields but rather large scale targets – treating the battle space as object, if you will. But, I’m hoping you could further explain how the process of urbanization in the Global South is being recharacterized by the west in such a way that has allowed the U.S. military to retool their doctrine for greater technomilitarism and its use in guerilla warfare. Is it fair to say that the poor cities of the world are being re-imaged by the west specifically to justify a shift in military strategy and to legitimate a ‘

Long War’?

[Stephen Graham] This is certainly a very important shift. Along with the portrayal of the ‘internal colonies’ of inner urban cores in U.S. or UK cities, or the Parisian banlieus, as Hobbesian spaces housing the dangerous, racialised other, military and security discourses about global south cities depict such places as essentialised, Hobbesian places of anarchy. One influential article by Richard Norton, for example, calls such places

“feral cities” which threaten global capitalist order because they house massive populations, create social and political unrest, are often not governed in any formal sense, and provide breeding grounds for extreme ideologies. Fear of ‘failed cities’ thus seems to be even more powerful than fear of ‘failed states.’

A key writer in this vein is

New York Times columnist, and self-styled urban warfare commentator, Ralph Peters. Peters’ military mind recoils in horror at the prospect of U.S. forces habitually fighting in the majority world’s burgeoning megacities and urbanizing corridors. To him, these are spaces where “human waste goes undisposed, the air is appalling, and mankind is rotting” (1996, 2). Here cities and urbanisation represent decay, anarchy, disorder and the post-Cold War collapse of ‘failed’ nation states. “Boom cities pay for failed states, post-modern dispersed cities pay for failed states, and failed cities turn into killing grounds and reservoirs for humanity’s surplus and discards (guess where we will fight)” (1996, 3).

Peters highlights the key geo-strategic role of urban regions within the post-Cold War period starkly: “Who cares about Upper Egypt if Cairo is calm? We do not deal with Indonesia – we deal with Jakarta. In our [then] recent evacuation of Sierra Leone Freetown was all that mattered” (1997, 5). Peters also candidly characterises the role of the U.S. military within the emerging neoliberal ‘empire’ with the USA as the central military enforcer (although he obviously doesn’t use these words – see

Hardt and Negri, 2000). “Our future military expeditions will increasingly defend our foreign investments”, he writes, “rather than defending [the home nation] against foreign invasions. And we will fight to subdue anarchy and violent ‘isms’ because disorder is bad for business. All of this activity will focus on cities”.

[Image: An ironic symbol remains in tact in Saddam's crumbled palace just after the American Invasion following the aftermath of 9/11.]

[Image: An ironic symbol remains in tact in Saddam's crumbled palace just after the American Invasion following the aftermath of 9/11.]Again, in synchrony with his colleagues, Peters sees the deliberate exploitation of urban terrain by opponents of U.S. hegemony to be a key likely feature of future war. Here, high-tech military dominance is assumed to directly fuel the urbanisation of resistance. “The long term trend in open-area combat is toward overhead dominance by U.S. forces,” he observes (1996, 6). “Battlefield awareness may prove so complete, and ‘precision’ weapons so widely-available and effective, that enemy ground-based combat systems will not be able to survive in the deserts, plains, and fields that have seen so many of history’s main battles.” As a result, he argues that the United States’ “enemies will be forced into cities and other complex terrain, such as industrial developments and inter-city sprawl” (1997, 4).

To Peters, and many other U.S. military commentators, then, it is as though global urbanisation is a dastardly plan to thwart the U.S. military gaining the full benefit from the complex, expensive and high-tech weapons that the military-industrial complex has spent so many decades piecing together. Annoyingly, cities, as physical objects, simply get in the way of the U.S. military’s technophiliac fantasies of trans-global, real-time, omnipotence. The fact that ‘urbanized terrain’ is the product of complex economic, demographic, social and cultural shifts that involve the transformation of whole societies seems to have escaped their gaze (see Peters, R. (1996),

“Our soldiers, their cities”, Parameters, Spring, 1-7; Peters, R. (1997), “The future of armored warfare”, Parameters, Autumn, 1-9).

The supposed geographies of ‘feral’ global south cities certainly loom large in the imaginative geographies sustaining western military doctrine for urban areas. The physical and, electronic simulations being produced by western militaries to train their forces are increasingly including garbage dumps’, ‘shanty towns, industrial districts, airports,’ and subterranean infrastructures.

The key thing about western military operations in global south cities is that they force military groundedness in militaries that are much more comfortable trying to dictate things from the air using superior sensing and firepower. In Baghdad, high-tech western surveillance and targeting have not allowed U.S. forces to triumph over determined insurgents utilising very basic and old fashioned weapons and guerilla tactics. Instead, U.S. forces have had to go out on patrol through city streets. This has brought them into very close proximity with insurgents, who have been able to deploy ambushes, improvised explosive devices and rocket-propelled grenades to devastating effect.

A major response amongst U.S. military-industrial complex to try and reorganise the high-tech and technophiliac weapons and surveillance systems so expensively built up since the last days of the Cold war so that they directly address the needs to ‘situational awareness within the complex, 3d geographies of global south cities. Programmes with telling titles such as

‘Combat Zones That See’ and

‘Visibuilding’ promise to re-establish the dream of omniscient, distanciated and machinic vision for U.S. forces in cities, allowing them to once again withdraw physically from the killing power of their machines. Many dreams of robotised and automated high-tech warfare, permanently projecting perfect power into global south cities, are emerging here. The objective being to try and delegate the decision to kill to computer software embedded within networked weapons and sensors which permanently loiter within or above urban space automatically dispatching those deemed 'enemy'.

Take, for example, the thoughts of

Gordon Johnson, the

‘Unmanned Effects’ team leader for the U.S. Army’s

‘Project Alpha’ – an organisation developing ground

robots which respond automatically to gunfire in a city. If such a system can get within one meter, he says, “it’s killed the person who’s firing. So, essentially, what we’re saying is that anyone who would shoot at our forces would die. Before he can drop that weapon and run, he’s probably already dead. Well now, these cowards in Baghdad would have to play with blood and guts every time they shoot at one of our folks. The costs of poker went up significantly […]. The enemy, are they going to give up blood and guts to kill machines? I’m guessing not” (Herbert, 2003, 3)

An even more fetishistic technophiliac fantasy of perfect power emanates from the

Defense Watch magazine, in an article that appeared in 2004 in response to DARPA’s announcement that they were developing large scale computerised video systems to track the car movements in whole cities continuously. “Several large fans are stationed outside the city limits of an urban target that our [sic] guys need to take,” they begin:

“Upon appropriate signal, what appears like a dust cloud emanates from each fan. The cloud is blown into town where it quickly dissipates. After a few minutes of processing by laptop-size processors, a squadron of small, disposable aircraft ascends over the city. The little drones dive into selected areas determined by the initial analysis of data transmitted by the fan-propelled swarm. Where they disperse their nano-payloads.”

“After this, the processors get even more busy”, continues the scenario:

”Within minutes the mobile tactical center have a detailed visual and audio picture of every street and building in the entire city. Every hostile [person] has been identified and located. From this point on, nobody in the city moves without the full and complete knowledge of the mobile tactical center. As blind spots are discovered, they can quickly be covered by additional dispersal of more nano-devices. Unmanned air and ground vehicles can now be vectored directly to selected targets to take them out, one by one. Those enemy combatants clever enough to evade actually being taken out by the unmanned units can then be captured of killed by human elements who are guided directly to their locations, with full and complete knowledge of their individual fortifications and defenses […]. When the dust settles on competitive bidding for BAA 03-15 [the code number for the ‘Combat Zones That See’ programme], and after the first prototypes are delivered several years from now, our guys are in for a mind-boggling treat at the expense of the bad guys” (2004, sic.)

[Bryan Finoki] Needless to say, the military urbanism of today is clearly less about walls and traditional fortifications (even though we have hardly stopped building them), but really about an entire logic of a production of space and an artificial intelligent system for organizing and policing that space; one designed for control; urban space as a completely new medium that is conducive to contemporary warfare. But, just as much, it seems this new spatial dimension of the ‘war on terror’ has also turned the city into a medium for insurgency – what does this suggest about the perceived enemy who is now no longer outside the gates, but also hiding within now?

[Stephen Graham] As with so much of urban life, the key now is seamless merging of systems of electronic tracking, tagging, surveillance and targeting into the architectonic and geographical structures of cities and systems of cities. The production of space within the ‘war on terror’ thus mobilises an intensified deployment of these sensors and systems – through global biometric passports, global port management systems, glocal e-commerce systems, global airline profiling systems and global navigation and targeting systems – within and through the securitising fabric of urban places. This is very much a Deleuzian and rhizomatic process which helps to sustain the breaking down of the traditional binary of ‘inside/outside’ for nation states and instead brings urban and socio-technical architectures of security into a range of globe-spanning and telescoping assemblages which continually perform urban life.

[Bryan Finoki] In addition to the global-span of these surveillance technologies, there is also a rampant boom in border fence construction today following, ironically enough, the fall of the Berlin Wall. Not that these wall projects aren’t pushing the technological implications of peripheral national security, but I was curious of your assessment of the future of nationalism given this patterning of geopolitical border relations?

[Stephen Graham] Certainly architectures of control – architectonic and digital combined – are being mobilised with unprecedented scale in defence of national territoriality. But I think many of these projects are as much symbolic as practical. They are physical demonstrations that nation states can control global flows of people, goods and capital when, in many cases, this is simply not the case. So the future of nationalism will rely fundamentally on the degree to which it can move away from the idea of an imagined and homogenous community and, instead, come to terms with radical heterogeneity, especially in global cities. If it does not do this, we will see accelerating tensions between ideas sustaining urban governance and those sustaining national governance. For one thing, European nations and Japan, especially, will have no choice but to radically extend their immigration levels if they want to avoid the economic melt down that will come with geographic ageing.

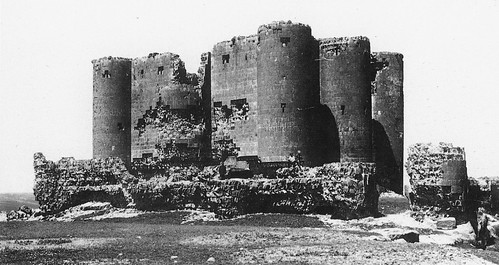

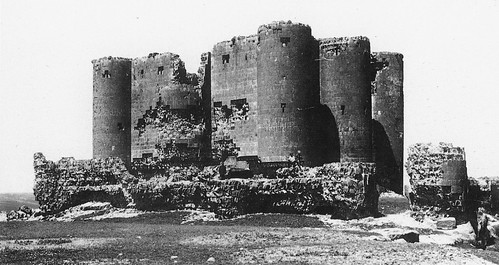

[Image: The fortress of Tignis.][Bryan Finoki]

[Image: The fortress of Tignis.][Bryan Finoki] Getting back to an earlier question, I read that the earliest forms of cities were built on forms of conflict and barricading against the natural elements. That is to say, at their root, cities are defined by a defensive kind of urban DNA, I mean – shelter, for all intents and purposes – could be construed as a primitive form of military urbanism. But, clearly we have come a long way towards full-scale gated communities now; what are the psychopathological implications of this morphology? Having moved from improvising mere shelter from the elements to complete enclave barriers against more abstract notions of fear, I guess my question is: how is the culture of an “Us” and a “Them”, or the “Other”, not only embodied in the current trend of security urbanism, but extensions of an ongoing pathological development?

[Stephen Graham] There is a major contradiction here. One the one hand, the Bush doctrine has simplistically relied on the constant invocation of a putative ‘us’ and ‘we’ marshaled against a threatening, monster-like, racialised and demonic ‘them’ who offer an existential threat to ‘our’ civilization and all its hallmarks (‘freedom’,’ democracy’ etc). Here we see long-standing Orientalist tropes being recycled.

On the other hand, it is clear that, in many ways, the cosy, folkish language of ‘homeland security’ fits very poorly with the transitional cultural, social, ethic and economic realities of U.S. metropolitan regions. So there is a major tension between the construction of a an imaginative geography of nationhood as ‘us’ and the reality of U.S. metropolitan region. I think this is caused by the fact that it is largely white exurban U.S. that forms the real heartland of the Republicans: the central cities are as alien, demonised and Othered to them as are Fallujah and Baghdad. So their ‘war on terror’ can be thought of as a war against cities both in their own nation and in the colonised war zones. At home this has involved a ‘cracking down on Diaspora,’ in

Andrew Shryock’s words.

Once again, then, Western nations and transnational blocs -- and the securitized cities now seen once again to sit hierarchically within their dominant territorial patronage -- are being normatively imagined as bounded, organized spaces with closely controlled, and filtered, relationships with the supposed terrors ready to destroy them at any instant from the ‘outside’ world. In the U.S., for example, national immigration, border control, transportation, and social policy strategies have been remodeled since 9/11 in what Hyndman calls:

"attempt to reconstitute the [United States] as a bounded area that can be fortified against outsiders and other global influences. In this imagining of nation, the US ceases to be a constellation of local, national, international, and global relations, experiences, and meanings that coalesce in places like New York City and Washington DC; rather, it is increasingly defined by a ‘security perimeter’ and the strict surveillance of borders" (see Hyndman, J . (2003) Beyond either/or: A feminist analysis of September 11th. ACME : An International E-Journal for Critical Geographies. (February 2006)

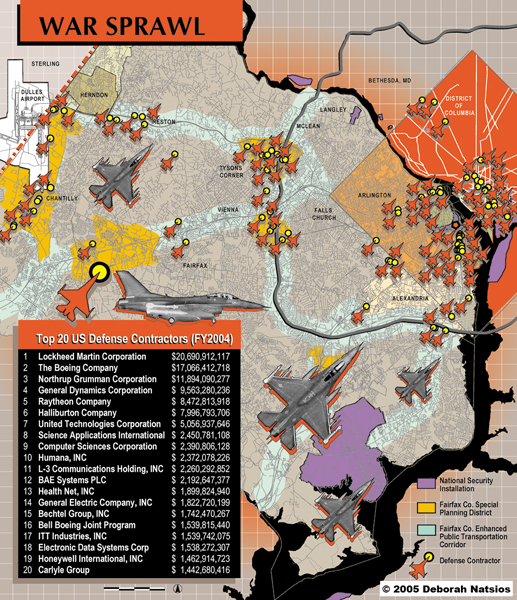

To architect

Deborah Natsios, meanwhile, the ‘homeland’ discourse “invokes both moral order” and specifically normalizes suburban rather than central-metropolitan urban conditions. The very term ‘homeland security’, in fact, serves to rework the imaginative geographies of contemporary U.S. urbanism in important ways. It shifts the emphasis away from the complex and mobile diasporic social formations that sustain large metropolitan areas through complex transnational connections, towards a much clearer mapping that implies more identifiable and essentialized geographies of entitlement and threat. This occurs at many scales -- from bodies in neighborhoods, through cities and nations to the transnational -- and delineates a separation that works to inscribe definitions of those citizens who are deemed to warrant value and the full protection of citizenship, and those have been deemed threatening as real or potential sources of ‘terrorism’: in essence, the targets for the blossoming national security state.

Amy Kaplan argues that the very word ‘homeland’ itself suggests some “inexorable connection to a place deeply rooted in the past.” It necessarily problematizes the complex and multiple diasporas that actually constitute the social fabric of contemporary U.S. urbanism. Such language, she suggests, offers a “folksy rural quality, which combines a German romantic notion of the folk with the heartland of America to resurrect the rural myth of American identity” (ibid. 88). At the same time, Kaplan argues that it precludes “an urban vision of America as multiple turfs with contested points of view and conflicting grounds upon which to stand” (ibid. 88 see Kaplan, A. (2003),

Homeland insecurities: Reflections on language and space. Radical History Review. 85: 82-93.).

Such a discourse is particularly problematic in ‘global’ cities like New York, constituted as they are by massive and unknowably complex constellations of diasporic social groups tied intimately into the international (and interurban) divisions of labour that sustain neoliberal capitalism. “In what sense”, asks Kaplan, “would New Yorkers refer to their city as the homeland? Home, yes, but homeland. Not likely.” Ironically, even the grim casualty lists of 9/11 revealed the impossibility of separating some purportedly pure, ‘inside,’ or ‘homeland city,’ from the wider international flows and connections that now constitute global cities like New York -- even with massive state surveillance and violence. At least 44 nationalities were represented on that list. Many of these were ‘illegal’ residents in New York City. It follows that, "if it existed, any comfortable distinction between domestic and international, here and there, us and them, ceased to have meaning after that day" (Hyndman, 2003: 1). As

Tim Watson writes:

"global labor migration patterns have […] brought the world to lower Manhattan to service the corporate office blocks: the dishwashers, messengers, coffee-cart vendors, and office cleaners were Mexican, Bangladeshi, Jamaican and Palestinian. One of the tragedies of September 11th 2001 was that it took such an extraordinary event to reveal the everyday reality of life at the heart of the global city," (2003: 109: see Watson T. (2003), Introduction: Critical infrastructures after 9/11. Postcolonial Studies. 6: 109-111.)

[Image: The decimated lobby of the World Trade Center in NYC after the bombings of Sept, 11th.]

[Image: The decimated lobby of the World Trade Center in NYC after the bombings of Sept, 11th.]Posthumously, however, mainstream U.S. media has overwhelmingly represented the dead from 9/11 as though they were a relatively homogeneous body of patriotic U.S. nationals. The cosmopolitanism of the dead had, increasingly, been obscured amidst the shrill, nationalist discourses, and imaginative geographies of war. The complex ethnic geographies of a pre-eminently ‘global city’ -- as revealed in this grizzly snap-shot -- have thus faded from view since Hyndman and Watson wrote those words. The deep social and cultural connections between U.S. cities and the cities in the Middle East that quickly emerged as the prime targets for U.S. military and surveillance power after 9/11, have, similarly, been rendered largely invisible. In short, New York’s transnational urbanism, revealed so starkly by the bodies of the dead after 9/11, seems to have submerged beneath the overwhelming and revivified power of nationally-oriented state, military and media discourses.

[End of Pt. 1: Bryan Finoki / Stephen Graham, 2007]• • •Pt. 2, I hope to post in the next few weeks, so stay tuned. In the meantime:

Check out:Stephen Graham, Professor of Human Geography at the University of Durham

Cities Under Siege: Katrina and the Politics of Metropolitan AmericaArchitectures of Fear: Terrorism and the Future of Urbanism in the WestRead

Pt.2 of The City in the Crosshairs: A Conversation with Stephen Graham.

Previous coverage of Stephen Graham on Subtopia:

Peering into the Arenas of War'Military Omniscience'Cities Made by War