The Green Yonder

[Image: Photo by Lubos Pavlicek/CTK/AP.]

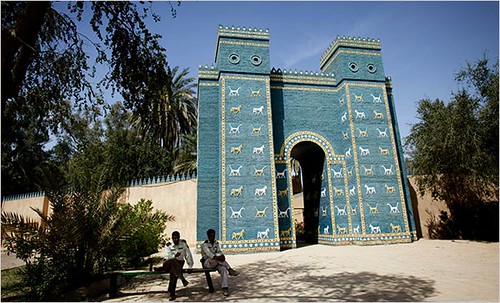

You may have read a few months ago the US began removing some of the street barriers that have propped up Baghdad’s security on a stilted network of blast walls and checkpoints for years, since—citing improved security—the Iraqi government is aiming to open all of the capital’s streets by the end of the year. As mentioned in this article, removal of the barriers is linked to “a security pact signed with Washington in November that requires US forces to withdraw from all cities and major towns by June 30”, (which some say is looking less likely already), “and from the country as a whole by the end of 2011.” We’ll see.

At the peak of the sectarian violence 88 streets were closed in Baghdad, we are told, and if the article is accurate, the government has already reopened 75 percent of them. However, reading on officials also state that many of the “the walls and T-wall anti-blast barriers” would still be kept in tact while the Green zone itself, which houses the Iraqi government and the US Embassy, will remain completely barricaded.

In Ghaith Abdul-Ahad’s 4 part video series for the Guardian -- City of Walls -- he traces the maze of concrete slab seemingly dropped from the sky into Baghdad to keep separate the Sunnis and Shiites, splicing neighborhoods and highways in half, and given how pervasive these walls still are all around the city it’s tough to imagine – despite the roads being opened – that Baghdad is getting on any kind of reunification track.

[Image: Blooming Iraq holds international flower festival/AP.]

Recently, Baghdad hosted a flower festival open in the streets to show how safety conditions are changing. But, as you know, there’s been a terrible new rash of car bombings recently that have taken hundreds of lives in just days, showing how tenuous the situation still is.

Yet, we read in the New York Times, despite the violence and the continued presence of the walls (which we’ve written about here on Subtopia numerous times already) many of the neighborhoods – having once held “a prevailing attitude of can’t-be-bothered, as seen in the buildings that went unpainted, crisscrossed by tangled wires from generators and satellite dishes, or the bomb debris just left lying”; that “smelled always of generator diesel and often of dead dogs, which rotted by the roadside untouched for fear they hid an I.E.D.,”; and where any “splotch of green” was “covered with thick dust”; further, when “Iraq seemed a place painted in desolation, and decorated with despair” – many of these neighborhoods are now apparently being revived by a wave of small scale landscaping projects.

Today, “buildings and walkways are trimmed by meticulously cared-for flower beds, with laurel hedges in geometric shapes, and so many roses that the breeze is fragrantly cloying.” All over, the Times continues, “fountains have started to spout again after years of disuse.”

[Image: Christoph Bangert for The New York Times, Iraq’s False Spring]

While taking such a flowery brush stroke to Baghdad’s battered landscape the article (aptly titled Iraq’s False Spring) is careful not to paint too hopeful a picture. Forgive the bulkitude here:

“This is not at all to say that the ugliness of a war zone isn’t still present. It’s pretty hard to make towering blast walls into a thing of beauty, no matter how much paint is deployed. Mad Max fortifications are still often the rule. Hescos — antiblast protection consisting of big wire containers of rubble — defy all attempts at decoration. They’re just huge piles of dirt. There are still many areas of the city where no one seems to have figured out whose job it is to pick up the trash.

One such area is the Green Zone. There, a series of murals of Iraqi landscapes, each stretching over three to six sections of blast wall, have been moved to protect an Iraqi Army camp, with no effort to keep them in the right order. The result is a crane-size jigsaw puzzle.”

However, if French businessman Jean-Marie Zimmermann has his way he will replace many of these concrete walls with trees and bushes and make the Green Zone truly green, he told the media recently.

[Image: The New Embassy Complex in Baghdad, Iraq. Photo via Sharon Weinberger]

Zimmermann works for Sinnoveg, “a 420-hectare nursery in eastern France” that develops "natural defensive weaved hedges" and “walls made from tightly bound thorny plants,” many of which have already gone to securing high profile sites, like “a nuclear research center outside Paris,” for example, “a juvenile detention centre, train stations and airports.”

[Images: Tree Nurseries Daniel SOUPE.]

Apparently, the company has patented its defensive line of woven organic fences and is the first to propose using these types of natural walls at such a scale.

Speaking about the Green Zone:

"This is the kind of place where we can provide protection. We can remake Baghdad as a city focused on nature, ecology and the environment, with a new concept of security," he (Zimmermann) says.

The principle is simple: plant a row of thorny trees and bushes 80 centimetres (32 inches) apart and weave the branches together. As the plants grow they form a dense and razor-sharp hedge that within three years can reach a height of six metres (20 feet).

Zimmermann said traditional barbed wire, tyre spikes, sensors and even metal barriers can be placed within the hedges -- an invisible back-up layer of security.

"A tank can go through but not a truck," he says.

Not really sure, but sounds to me like just another green-washed marketing tactic to get a big government contract, and sell the notion that anything green automatically equates to better no matter how shallowly “green” may even be defined (is weaved foliage in conjunction with other barriers really more green?); this also strikes me as ignoring the fact that simply greening the barriers doesn’t do anything to work away the need for them in the first place. In fact, it probably only helps cement the opposite: which is to say, masking the barriers will only probably contribute to a greater environmental acceptance of them in the long run and therefore help to sell their permanence, help to sell barriers in a more pleasant form, and thus might play into a more long term swell of Baghdad’s false sense of security, adding to negligence of pressing strategies and efforts required to truly work towards a situation where barriers no longer exist. You could argue greening the barriers might lead to greater danger in the long run, by deferral.

But, to be fair, could the these green barriers slowly replace the current ones, and if so could they help lead to a removal of all barriers in the end, which would include these same green things themselves? Maybe. But, simply substituting barriers in various forms means nothing to me.

[Images: Courtesy of Sinnoveg.]

Still, it might be interesting to dabble in what could happen if this traveling fortress-scaper gets to plant his heavy-duty strain of anti-terrorist blast trees and weave a crown of impenetrable hedges around the Green Zone.

Say, over the course of several weeks Sinnoveg rolls through Baghdad in a tight caravan of armored trucks. A couple of which are covered in thick grasses and bristling shields that go darting down the road like two giant earth covered couches on wheels in a surreal advertisement of their product.

Onboard a few are bundles of various trees stacked upon one another like a bed of precious missiles. Inside other trucks huge mattress-sized divots of crocheted foliage are hauled that will eventually be knitted together by a catalog of spooled root systems following behind them. Dozens of smaller pick-ups zip to the front and then to the back again with carpet rolls of specially grown sod and extraordinarily long and flexible coils of braided branches and treated sea kelps. Steady in the middle of the caravan military escorts move semi-transparent boxes the size of refrigerators cut for oxygen with bright green ferny tentacles ever so slightly poking through them -- they retract going over bumpy roads. The whole thing is a mysterious convoy of mobile greenhouses and nurseries scooting past Baghdad’s rubbled streets in a sunlit blur.

In no time at all dozens of crews operating remote-controlled weaver-bots with interchangeable grapplers manage to drape the entire Green Zone’s heavily fortified perimeter in a terrestrial curtain like some old school camouflage tactic. From outside the zone this mangy green wall looks like a sub-natural island rising up from the battle encrusted core of urban Baghdad. A new Emerald City. An unihabitable island. Even though some sections of T-wall are removed many simply vanish behind the dense imbrications of unraveled hedge-walls and strategically planted trees that blow and settle into place all on their own like a great curtain being shook by a invisible hand – it instantly comes to life. It’s as if a militarized wreath the size of a small city bioengineered for war is placed around the Green Zone, the only thing missing from these massive grafts of vegetation are small populations of black-chinned hummingbirds, roboticized wasps and atomic desert butterflies, a few experimental DARPA-operated tree squirrels and monkeys, and perhaps a no man’s land strip of fallen dates and olives, pistachios and kamah truffles buried under rare patches of fence grass along the outside of the tree walls’ now excessively vibrant border.

At first, everything looks hunky dory. Suddenly, a flase spring is in the air as if the Green Zone has been made a halo of photosynthetic wonder. Fragrant with intrigue of far-off gardens, the attitudes of embassy personnel and Iraqi interior working behind these lush enclosures (which have been green-guarded on both sides) are noticeably cooperative and chipper. Productivity levels spike briefly marked by the curtain’s sudden bloom. Invited by this refreshing circular arboretum everyone spends considerably more time outside sauntering along its tropical walkways where perfumes of hybridized barks and woods and floral blossoms are addictively inhaled over coffee breaks and Subway sandwiches, while the avenues the other side of the green curtain (despite being heavily patrolled) slowly fill with people from all over the city flocking to check out the Green Zone’s living security fence; it quickly becomes a very popular public attraction.

Food stalls pop up. Informal literature is distributed explaining some of the exotic horticulture. New flowers end up inside people's homes. In short, the green curtain seems to have won over everyone.

But, as months pass through an oddly schizophrenic season dredged in torrential rains, abnormal wind chills coupled with ballistic heat spells, and a particularly violent sand storm that swarms Baghdad for a week leaving thousands plagued by wretched allergies, the fertile shield continues to grow, quite wildly in some parts in fact – so much so the entire thing looks weirdly out of harmony with itself, like a gangly teenager struck by uneven growth spurts in his limbs – the project soon requires incessant pruning in order for Sinnoveg to maintain its mastery of it.

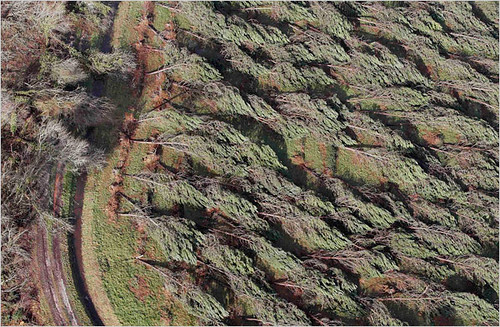

[Image: Much of central Baghdad was barely visible through a thick dust storm that blanketed Iraq's capital. Three bomb attacks killed 34 people and wounded dozens more in Iraq on Monday. Photo: Hadi Mizban/Associated Press.]

But the pruning is only good for so long. Propagating at frightening pace, the curtain first chokes off a couple key checkpoints into the Green Zone so they cannot be used again, at least until Sinnoveg’s emergency team of hedge techs can be flown in to perform serious amputations of the green wall. By the time they get there however the bulk of the hedges have grown far beyond any anticipation and Sinnoveg reluctantly admits they’re a bit unprepared to deal with the curtain’s manic growth.

Meanwhile, Baghdad hacks through an allergic disaster sneezing violently and coughing up little sacs of blood, rupturing septums with incessant snorts and clogged bellows, flinging constellations of slime everywhere from their nostrils while simmering winds keep it all astir.

Zimmermann’s hedge techs try to come out at first every month, then every week to inspect and saw away the excessive growth, but even they cannot believe their eyes. In the words of one supervisor, “the hedges have taken on more than a life of their own, they’ve gone completely mad – I think they’re possessed!” – they're no longer held in check by the harsh climate Sinnoveg anticipated making their maintenance work much easier.

They take up full-time residence in the Green Zone bunking in old US Army barracks and leftover trailers used to house American bureaucrats before those folks were shifted into blast proof apartments. But, even working 'round the clock through delirious shifts of nocturnal overtime they can’t keep the tree walls and monster hedges down. No matter how much they hack and haul away the missing volumes usually replenish within a couple of days and then grow even more. And the discarded greenery always has a way of going missing. Unless they burn it over permanent fires that emit strange fumes the piles either blow away or just “magically slip off somewhere,” one worker is overheard saying. “It’s the strangest thing. I swear this stuff slithers like a bed of snakes.”

Another employee claims to watch a set of branches cultivate more than a foot overnight prompting the installation of surveillance cameras to monitor the curtain’s late night growth cycles. But the hedges soon crush them and they become irretrievable. “The climate here is having an incredible effect on the hedges, no one ever expected them to take off like this, certainly not here,” Sinnoveg’s chief botanist says at a press conference. Not only is everything spurting uncontrollably, he goes on to explain, but the entire thing has its own intelligence of weaving itself together in far more intricate and formidable patterns than Sinnoveg’s engineers can ever dream up. Unsure of what the hell to do the engineers simply take pictures and notes.

[Image: By Paul DeCelle.]

By the end of winter most of the entry points to the Green Zone are completely stitched shut by feral vines, and Sinnoveg’s boys are more or less beaten down. Their weaver-bots working furiously in reverse all burn out. Their tools prove completely ineffective, and their ideas run abundantly low.

Soon, one by one all of the checkpoints are sealed by this creeping drapery so impromptu emergency bridges are slung over canopies extending 30 to 50 feet high in some areas, where bureaucrats climb like nauseated refugees fleeing their own compound.

With the help of the US Army Sinnoveg tries to dig a couple of tunnels below the curtain but the roots are tangled so deeply underground they are as impenetrable as the woven fences above.

Most people remain inside the zone even more than they already do for fear the hedges will grow too much in a single day and they may not be able to get back in over the makeshift bridges later. Of course, all of this prompts major security concerns and Green Zone patrols are beefed up on the highest alert while new waves of tension ripple through out the city.

Zimmermann now dangles in a thicket of bad publicity and like the Green Zone is going under fast. The Iraqi government calls in a special team of scientists to investigate the situation who immediately notices the Tigris’ River's water levels dropping frighteningly fast. Not only is the Green Zone’s new ecological upgrade completely taking over the compound but it is leaching the ancient water source in staggering amounts. More mild pandemonium sets across the city where random green parks have begun to spring up, strange patches of fresh growth in very unassuming places. Wandering gardens. Exotic alleyway flowerbeds. The city collectively sneezes.

[Image: Garbage on the Tigris By Christoph Bangert.]

Operating inside the Green Zone is a logistical nightmare made worse by the fact that to completely abandon it at this point is not even possible because there’s no way to get everyone out safely without pulling off a helicopter mission military officials say would be too dangerous because it would expose everyone to insurgent attacks.

[Image: From the lawn of the White House. Photograph: Jim Young/Reuters.]

Essentially, they're locked in. Food products and critical items are broken down into a continuous flow of smaller deliverables that have to be kept moving through a kind of stealthy aerial smuggling operation. All the while the mutant tree walls continue to grow and even change shape so they look less like walls and more like mounds leftover from ancient builders; the great wreath soon becomes a miniature mountain range ringing the Americans inside as if it were a green mustached volcano mouth. From the rest of Baghdad’s perspective, a jungly cloud has swept over the imperial zone and turned something heinously historic into an uninhabitable wild island.

[Image: Photo: Regis Duvignau/Reuters.]

Where once a space between the Embassy and its own inner ring of walls functioned as a separate layer of security or as a temporary promenade with little shops dispersed along side other outdoor spaces, the rabid hedges and sidewinding green tentacles completely consume this zone and begin to latch onto the Embassy structures themselves; in some cases baby hedges hatch from inside the buildings. Offices fill with strange mosses, hellish tufts of weeds break through concrete walls into the shiny new dining facility, the America Club is quickly mildewed by funky algaes, and the hospital turns into an oversized salad bar. Hedges soon sprout everywhere, inside closets, under diplomatic beds, the embassy becomes a Sinnoveg archive of hedges.

With their perimeter fatally compromised the US Army starts to panic about insurgents climbing over the mounds and through the haunted trees to inflict harm on the stranded embassy personnel. Yet, most of the personnel claim they are trying to escape from the zone not because they fear that sort of violence but because they feel “stalked by the green curtain.”

And there might be some truth to that. Not one supposed insurgent ever bothers to climb over this incredible concentric forest, especially not once the media announces that a couple US soldiers assigned to monitoring a temporary passage in the North West of the zone have disappeared and their bodies not yet found by the army, which of course triggers additional reports of Iraqi taxi drivers going missing near the curtain, and even some small children.

Baghdad’s violence is actually rather quiet during this whole ordeal, ironically enough. It’s simply more urgent to watch the nightly news reports or even go see firsthand these rabid and viral gardens flourish in the heart of the city and claim the compound’s brutal architecture than to think about neighborhood violence. The gardens are forcing everyone out of the Green Zone like rats from a flooded hole, and the site of this alone has Baghdad in its grips and blowing their noses.

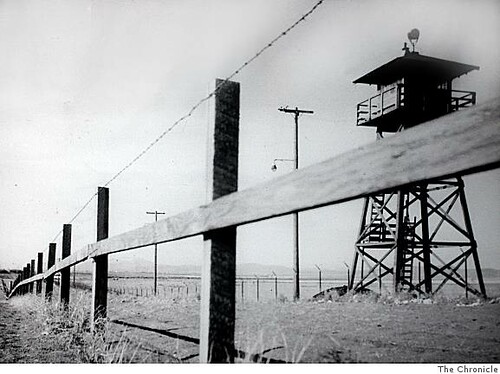

Months grow thick and Zimmermann’s arrogant claim to make the Green Zone truly green haunts him across newspapers all over the world. But he refuses to leave and takes up a position atop a watchtower that pokes up from the center of the compound where he continues to order his scrambling mad technicians, at least those who have stuck around. At one point he instructs them to bail from their own car bombs packed with incendiary explosives at the heathen hedges, hoping this will blast through them. But the hedges are inviolable and the great curtain merely shakes the burning vehicular corpses off before consuming them. His men try everything from flamethrowers and ultrasonic weapons to high-density lasers to suppress the hyper lattice of stems and green cords cinching in on them from every angle, but only makes it all grow back and sew itself together with vengeance.

As we said, all this time the political violence stops but few notice. Instead, the Americans manage to scramble to random corners of the city waiting for airlifts to other camps in the region while a local filmmaker surveys the scene on the ground with camera crews eager to capture the final days of the main palaces of Saddam Hussein – and now the imperial bunkers of the American regime -- as they are finally ready to be overtaken by an incredible surge of nature, to be toppled by no man but millions of mice and insects and tiny birds instead that suddenly spawn to pick apart the hubris remains of Empire’s overreach before everything in the zone is completely devoured and the cradle of civilization is turned into a swath of insatiable "greenery."

For weeks Baghdad’s anxious crowds gather around the rough green edges to watch the modern fortress buried over. What seemed impossible years ago takes Baghdad by storm in just a few weeks. The film crews race around the brambly mess daring into it to get footage of the final days of the elegant marble building used by the Iraqi Governing Council before it succumbs to an army of woven knots and cables, prowling nooses, and the thuggish push of the Sinnoveg's rogue hedges.

On televisions all over people watch the verdant cocooning of tin trailers and the slow grassy ground invasions of abandoned military camps and feeble barracks wilting under the vines and being consumed overnight like worthless shelter carcasses. Lightweight tent structures and abandoned vehicles drown in thorny thickets, while an empire of sprawling kudzu ivy spreads over the entire site and covers it and roughly all 30 or so buildings in the Zone so the media begins referring to a “green blanket” rather than “the green curtain” it once used to be.

100 acres of urban space suddenly turned into an orgying jungle spiked with modern ruins; the crowned jewel of empire now a giant bomb crater filled in instantly by fresh green earth; call it a post-imperial Oz or the greatest Crack Garden ever spawned, it’s the world’s “ultimate gated community” torn down by a spontaneous green yonder.

[Image: Photo by Christoph Bangert.]

Cameras hang from balloons and relay shots of the complex’s apartment buildings and the hospital disappearing inside layers and layers of green bubble wrap, with one last blocky concrete islandtop resisting the tree lines upon which Zimmermann stands on a wobbly chair. Looking down upon the green yonder with a tormented grin, a fiendish vortex of ferny tentacles lap at the base of his pedestal. He looks out over Baghdad and sees it besmirched by wicked plots of strewn greenery now. Lilypads swell in his eyes.