Well, of all the conferences, exhibitions, art shows, Biennales, funky parties, boring ass lectures, academic/pseudo-academic love/hate nerd-fests out there; of all the ridiculously cool underground and even annoyingly pompous events happening at this very moment [not to mention the No Borders Camp social action gathering coming up and all the other cross-border cultural stuff going on this summer that I have absolutely no idea about still at this point] – of All that stuff, The ONE I dream of being flown out to right now, right NOW -- in order to cover for Subtopia (somehow, someway) -- I have to say, the one I’d be going to is in Barcelona, Spain, called simply enough "

Fronteres,” or (as you probably guessed) “Borders.”

Yup. A big old installation dedicated to the geopolitical ramifications and complex patterning of the world’s contested border zones.

Photos,

videos,

multimedia installations,

guided tours within the gallery of different political fault lines as depicted by large scale images and maps, writers and researchers, there is an even a section dedicated to exploring

border music in Istanbul.

Download the catalog here.

Regardless, I am going to repost the “Fronteres” press release and exhibition outline below for my own future reference. For now, I'll just have to sit back and hope that some of our lucky Spanish located readers will take the time to kick back with us a few afterthoughts on this one.

The Press Kit for "Fronteres":

The

Centro de Cultura Contemporánea presents the exhibition Borders, a reflection on the concept of the border, its types and a review of some of today’s geopolitical borders (the boundaries of Europe, US-Mexico, Israel-Palestine, North Korea-South Korea, Kashmir, Miami-Havana, the case of Melilla...).

The exhibition is designed as a journey through different worlds, in a movement that brings together history and geopolitics, the gaze of photographers and eye-witnesses, sounds and maps, general reflections and field studies.

As visitors make their way round the exhibition they’ll find photographs by Patrick Bard, Olivier Coret, Marie Dorigny, Olivier Jobard, Nicolas Righetti, Frederic Sauterau, Eric Roux-Fontaine and Michel Semeniako, and the reflections of Roger Bartra, Zygmunt Bauman, Georges Corm, Manuel Cruz, Francisco Fernandez Buey, Michel Foucher, David S. Landes, Tzvetan Todorov and Eyal Weizman. Also taking part are the creators Frederic Amat, Enric Massip, Angel Morua and Josep Niebla.

Borders, curated by the French geographers

Michel Foucher and

Henri Dorion, is a co-production of the CCCB and the

Musee des Confluences de Lyon (Departement du Rhone), which was

presented from 3 October 2006 to 4 February 2007.

It will run at the CCCB from 4 May to 30 September 2007. PROLOGUE FROM THE CATALOGUE BY JOSEP RAMONEDA In the labyrinth

PROLOGUE FROM THE CATALOGUE BY JOSEP RAMONEDA In the labyrinth The border, as

Claudio Magris said, is an idol at whose altar many lives have been sacrificed. Borders define an inside and out, one of them us and one of them the other.

There are many types of border: physical, political, cultural and even psychological. A border creates an interior space which seeks to be homogenous and purposely different from the outside one. Frontiers are also invisible barriers which come between people, even in personal relationships. We live in a time of flows: of the permanent and potentially unlimited movement of people, goods, money and ideas. And, nonetheless, we talk about borders more than ever. Governments find it easy to respond to any conflict – bloody or otherwise – by building or reinforcing borders, even though they know that it will be increasingly difficult to lock the door.

We are at a time of change between old and obsolete certainties and new references to be discovered. The physical, political, cultural, ideological, psychological and spiritual demarcation lines are on the move and the world is a choppy sea. The fall of a physical border doesn’t automatically mean overcoming psychological and cultural barriers. At the same time, borders are constantly being built which are difficult to mark out physically but have an undeniable social efficiency (or perhaps this isn’t the meaning of the discourse of the clash of civilisations?). In any case, the convenience of homogenous spaces, bounded by a single large border and with internal divisions, which under no circumstances questioned the unity of the national framework, is passing into history.

Any individual identity is a small space protected by physical and mental forms which separate us from the other to make us into an autonomous subject. Using these as a starting point, with the interplay between passions and interests, we emerge from ourselves and establish interrelations with others. Personal pronouns remind us of this in each sentence.

The same thing happens in the collective sphere. And in this regard,

Zygmunt Bauman is right to present the border as the third element between cultural diversity and the unity of the human species. The border is exclusive, but it is also constructive.

Borders rise and fall. Today they close, tomorrow they open. It is this interplay between the apparent regulation of flows which won’t prevent a growing global interrelation.

This exhibition looks at borders by exploring the edge territories which, in some way, express the contradictions of a world that moves between hypercommunication and deep fractures. The more we join together, the more labyrinthine the world becomes.

Josep Ramoneda Director, CCCB

Guided visits to the exhibition “Borders”Guided visits to the exhibition “Borders” by writers, journalists and experts who have worked on it and analysed the subject and who, with their knowledge, give us greater insight into the theme.

This cycle of guided visits is organized in the conviction that crossing borders helps us to see and understand. With the help of people who have worked on, studied and experienced in depth the borders they present, it sets out to teach us something more about them.

0 -

INTRODUCTIONThe contemporary world is crossed by over 226,000 kilometres of land borders. The European Union has long been engaged in a process of devaluation of these barriers, and, during this time, “without-border” organisations have become legion, globalisation has called for the removal of obstacles that prevent the circulation of people, products and images, and border issues have never been so widely discussed. But, why? This is what the exhibition Borders explores, using an approach linking history and geopolitics, photos and eye-witness accounts, sounds and maps, general reflections and field studies.

In turn, fronts and frontiers, links and separations, stitches and cuts, caesuras and interfaces, these lines which map out borders contribute to identity. For an “inside” to exist, it must open on to an “outside” which can accommodate it. Everyone must take on their role as Hestia, the keeper of the hearth, and their role as Hermes, nomad, wanderer, master of exchanges, waiting for encounters, the god of paths and guide of travellers.

Crossing borders helps us to see and understand. Looking beyond means taking the risk of venturing on to a foreign continent, of facing up to a different horizon, of being surprised by new faces and finding oneself without a home, without identity or, at least, implicated. A mirror effect. The exhibition Borders has been conceived as a journey, through different worlds. We know how to enter them. What will we know at the journey’s end, once we have crossed the final boundary?

The exhibition begins with a mural by

Josep Niebla : Patera no. 1

1 –

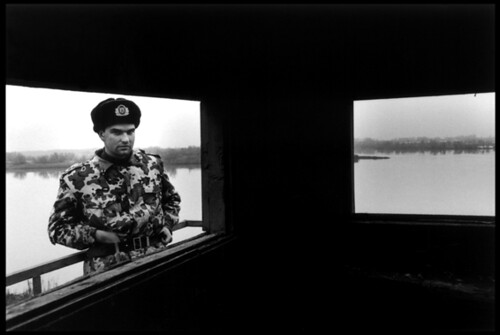

THE BOUNDARIES OF EUROPEThe borders of Europe and the question of its boundaries: from the Aegean Sea to the Barents Sea. Screening of photographs by

Frédéric Sautereau who, together with the journalist

Guy-Pierre Chomette, undertook a journey between June 2000 and August 2003, during which they followed the borders of Eastern Europe.

"The maritime and terrestrial borders of the expanded European Union stretch from the Canary Isles and the Straits of Gibraltar to the Aegean Sea, the Black Sea and Barents Sea. The Turkish question has triggered a salutary debate about the borders of Europe. Classical geography has marked the boundaries on the continent inappropriately (the Urals split Russia in two and the Bosphorus connects both sides of the city of Istanbul, although, by convention, it separates Europe and Asia). Europe as a civilisation defined a secular cultural identity, Europeanness, the feeling of cultural belonging, the legacy of Christianity and the Enlightenment. Since 1957, Europe also denotes an idea, a project founded on a European identity and awareness which have resulted in an organisation: the European Union. The integration of Poles, Hungarians and Balkans in 2004 amounted to history encountering its geography.

Although there is no definitive answer to the question of Europe’s boundaries as a continent, the question of the political borders of a Union of States sharing a common project depends on the choice of its citizens and their powers of attraction to their borders. Since 2004, the Union has brought together countries at the heart of Europe. With Turkey, Ukraine and the Balkans in crisis, we would need to include those countries which, for centuries, have been on the periphery of Europe, at the edge (the word Ukraine means borderland). Hence the current uncertainty. Without a geography given once and for all by nature, Europe must rely on its history and project in order to define the relationship it wishes to build between its inside – the heart – and its outside – its periphery. In view of the fact that geography doesn’t come to the aid of politics, it is up to the Union of States to determine its political geography, by public debate. "

Michel Foucher

From the Aegean to the Barents Sea, a journey along the eastern borders "Among the ten countries that joined the European Union on 1st May 2004, six were on its eastern marches: Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia. Bulgaria and Romania were to follow in 2007 or 2008. The European Union thus acquired a new eastern border, and with the new border, came new neighbours. Turkey, Moldavia, Ukraine, Belarus and Russia were now on the other side.

A new division of the continent? Even if it is in no way comparable with the Iron Curtain – a painful split which set the west and east of Europe against one another for 40 years – the new eastern edge of the European Union raises new stakes and a great many questions. In certain remote regions, it highlights, in particular, the division of people scattered here and there, and disrupts the relations between neighbours which have been gradually re-established since the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the break-up of the Soviet Union in 1991. From the river Evros, between Greece and Turkey, to the desolate landscapes of the Arctic tundra on the Kola Peninsula, via the Trans-Carpathians and the Estonian rivers of Lake Peipus, who are the border inhabitants of the Union? What is their history? What is their day-to-day experience of living with this new European architecture? How are they affected from a moral and psychological point of view? By gathering eye-witness accounts on the west and east sides of the border, Guy-Pierre Chomette and Frederic Sautereau are trying to answer these questions by combining their editorial and photographic approaches. They went on seven journeys between June 2000 and July 2003, along this border, which runs for over 7,000 kilometres from the Aegean to the Barents Sea. These are described in a book, Lisieres d’Europe (The Edges of Europe), published by Autrement."

Photographer

Frederic Sautereau

Oeil Public

Journalist

Guy-Pierre Chomette

2 –

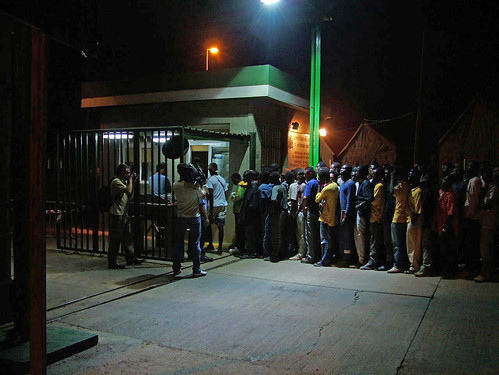

CLANDESTINE ITINERARIESThe challenges of migration in the world (the European case): images of Kingsley’s journey around Cameroon, Niger, Nigeria, across the Sahara, Algeria, Morocco, the Western Sahara and across the Atlantic. Photographs by

Olivier Jobard with voice-over by Kingsley

Migrations

Migrations "There are an estimated 185 million migrants – men and women – worldwide, according to the latest report by the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) in Geneva. The main destinations are North America (35 millions immigrants in the United States), Europe, the Middle East and South East Asia. Latin America, Sahelian Africa and the most heavily populated countries of Asia are the main regions of departure, while Mexico and North West Africa are zones of departure and transit. Almost two thirds of the world’s immigrants and refugees come from nine countries in Asia (Bangladesh, China, India, Pakistan, Indonesia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Sri Lanka, Thailand), the departure and arrival zone for economic migrants. People escaping a conflict or poverty (the Middle East and Africa), looking for seasonal employment (in Southern Europe, the United States and South East Asia), temporary employment (in Asia and the Middle East) or a more permanent job (North America, Asia, Europe), wanting to go into higher education (China, Vietnam and India encourage people to return home once they have received their qualifications). If people aim to leave their country of origin for good, they tend to choose to settle in the United States, Canada, Australia or the United Kingdom. The IOM estimates that remittance flows to the countries of departure are in excess of 120 billion euros."

Michel Foucher

Kingsley: Travel journal of an illegal immigrant. "It was in the year 2000, while I was producing a report on the Red Cross centre in Sangatte, northern France, that I became aware of the consequences of all the conflicts I had witnessed: Bosnia, Kosovo, Afghanistan, Kurdistan, Chechnya, Somalia, Sudan, Liberia, Sierra Leone... The population exodus.

Before, while I was working on my reports, I was quite happy just to pass people by, focusing only on the event itself.

In Sangatte, the last caravanserai for many illegal immigrants before the final stage, England, I made time for them.

While I was working on two so-called “topical” reports, I went back to visit these men who, from one day to the next, abandoned a past, a culture and a family for a new life which they dreamt would be better.

I listened to them talk about their journeys, their suffering, their hopes, their fears. Sometimes I was able to give them news about their country. It was through these exchanges that I felt the need to share their experiences in order to put a name to, and tell the story of those people commonly referred to in France as “sans-papiers”, or “without papers”.

So I decided to follow the route taken by one of them.

I met Kingsley in Cameroon while I was working on a report about illegal immigration. This young man of 22 had already set off into the unknown two years earlier but had been forced to turn back due to a lack of money. Since this abortive attempt, he had saved up and gained a great deal of support from his loved ones. His best friend and former workmate, Francis, had managed to emigrate to France legally by marrying a French tourist, and was waiting for him there. So, Kingsley was ready to set off again.

He left his country in May 2004 and travelled illegally through the whole of Nigeria and Niger, crossing the Sahara Desert to Algeria. Finally, he reached Morocco. It was here, after three months of waiting and two spells in prison, that he set out on a makeshift boat provided by people traffickers, together with some 30 other illegals, bound for the Canary Isles.

Six months after he left Cameroon, after changing identity five times and nationality three, he landed on European soil at last ... escorted by members of the Civil Guard.

At the beginning, our relationship was based on a common interest to take our enterprise as far as possible. When he suggested I be present when one of his friends handed him some money, I realised straightaway that I was his moral guarantee. Later, he asked me to look after his money so that he wouldn’t be robbed while crossing the different borders. I agreed, knowing that if I kept his savings, he would do his utmost to find me again if we were separated from one another.

Stronger bonds were gradually forged as a result of the difficult times we had shared. An almost unshakeable trust was established. The experiences we had lived through and the mutual respect we had for each other bound us together. I admit that I often vacillated between the role of observer and the role of actor throughout this story, until the time Kingsley obtained his residence permit.

Because he trusted me, he allowed himself to be featured in the newspapers while he was still illegal. I told him that this media coverage would possibly allow him to put together a solid dossier which would secure him special dispensation to remain. This is what happened. He now lives in France, where things are just about ticking along.

At a time when merit is a virtue that is much bandied about by politicians, when “risk-taking” and “putting oneself in danger” are raised to gold-standard levels, I would like to expose, through this report, the difficulties of such journeys and bring to light everything these migrants give – sometimes even their lives – in the hope of a better existence."

Photographer

Olivier Jobard

Sipa Press

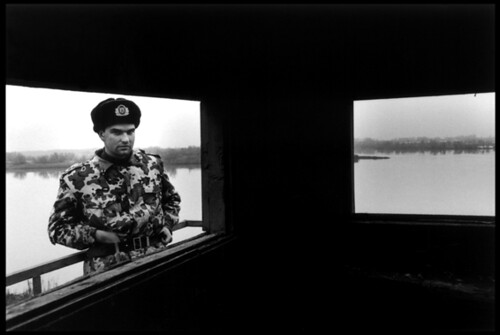

3 –

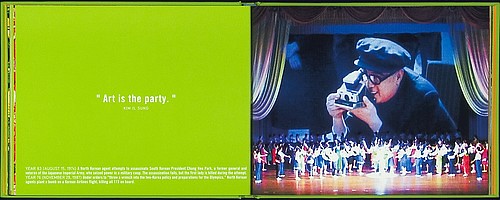

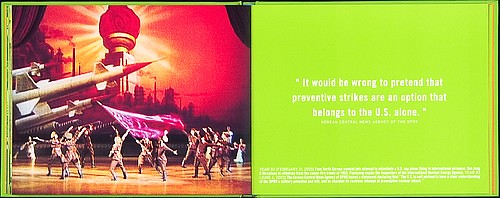

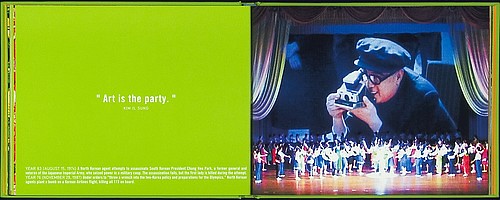

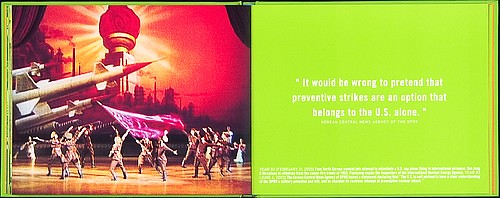

THE LAST PARADISE Borders that remain closed: North Korea is one of the last examples of an isolated world, hermetically closed by militarized borders that are almost impassable to its inhabitants, where the regime maintains an autarchy characteristic of bygone days and reserves the benefits of foreign contact for a minority. Screening of

photographs by

Nicolas Righetti A theatre where the box office is closed

A theatre where the box office is closed "Here is one of the latest examples of a closed world, hermetically sealed by militarised borders which are almost impossible to cross by its inhabitants, where the regime maintains an autarky from another age, while reserving, for a narrow caste, the benefits of outside contacts.

The Korean Peninsula, which was united for many centuries, has been divided into two states since the war in 1953, in which five million people were killed. This was the aftermath of the Cold War. In the south, a modern, democratic State, a world- ranking economic power which jealously guarded its independence from China and Japan, supported its American ally. In the north, the world’s most reclusive regime, overarmed, calling for nuclear status but unable to protect its inhabitants from risks of famine, and keeping its population in a giant labour camp presented through the theatrical fiction of a communist paradise. The People’s Republic of North Korea is supported by China to counterbalance the military presence of the United States in the region and the ambitions attributed to Japan. The inter-Korean border comprises a demilitarised zone, 4 km wide and 239 km long, which is guarded night and day. The world’s 6th and 7th armies – or 1.7 million soldiers – face each other at the border. We no longer count the tunnels built by the troops from the north. The capital of the south, Seoul, 40 km from the border, is vulnerable. Talks have been held between the two Koreas. The unification of Germany has been analysed by the South Koreans. But the isolation imposed on North Korean society doesn’t lead us to expect an outcome comparable with the one in the former GDR."

Michel Foucher

The last paradise: North Korea

The last paradise: North Korea ""We are happy", an enormous slogan written in Korean: white script on a red background. The first sentence translated for me when I arrived on the tarmac in Pyongyang. I am happy too. I feel moved to be here, to have finally managed to set foot in one of the most reclusive states in the world. It has only taken nine years of manoeuvring to get a visa and four invitations extended through official channels. Four trips there and back, each proving to be more alike each time. The earthly paradise created by the charismatic leader Kim Il Sung is quite unlike the one imagined by Christian society: you can go there and leave.

As you come out of the airport, the world is turned upside down. No advertising, no movement, no sellers, no noise, no animals, no Asia. The country lives in isolation, and the prevailing atmosphere is that of a citadel under siege. On the road taking us to the capital there are only silent, uniformed pedestrians, walking in their hundreds on the verge. The many soldiers, standing straight in full military gear, are ready to intervene against the imperialist threat.

Han, my official guide, is always there to keep me on the right path. We are still happy. He is convinced of my unconditional love for the regime. I have to capture the propaganda on my film. He presents me with the same schedule for my stay. The same itinerary. The same timetable. Taken aback, I point this out to him. “Yes, it’s true, but people seldom visit twice”, he says, with some surprise. Daily visits here are put on record, hour by hour, because each foreign delegation staying in the paradise is treated in the same way. And I’m a foreign delegation in my own right. They’ve given me such a heavy schedule that I can’t get out of it. I’m irrevocably tied to this glossy piece of paper. The house where Kim Il Sung was born, the triumphal arch, the Museum of International Friendship, store number one, the Juche Idea Tower, the Children’s Palace. There is no show of power without the appropriate setting. The capital is a vast communist Hollywood. The same attractions for the same emotions. As I travel the city by bus, I pass quickly from one scene to another. Interior, exterior, everything seems false.

During my second trip, I realise that the important thing is not to reveal what lies beneath a totalitarian stage set, but to show the country as you see it. I decide to film the artificial happiness of the ceremonies I am invited to. Just like Alice in Wonderland, I finally go through the looking-glass. I make reality out of fiction. Unless, of course, fiction is the reality.

The whole experience fills me with unexpected joy. The happiness at discovering a simple, clean, tidy and flawless world. The great strength of the North Korean visual universe lies in being uniform, homogenous and repetitive. All these "I love Comrade Kim Jong Il, the strongest man in the world ", "Think, speak and act like Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il, our beloved leaders", and the portraits that embellish each apartment, official building, dining room, are very real. To see and be seen: this is the function of these effigies which take pride of place in every home, like a placid Big Brother with slanting eyes. The people pin onto their chests a badge bearing their image. Nobody escapes the authorities’ gaze. I am a child in the Garden of Eden, and the figure of God the Father is my guide. Even though he’s dead, “Kim Il Sung still lives among us”. This is where life begins. There is no other. Kim Il Sung is everywhere. Kim Il Sung is God. His son, Kim Jong Il is the Messiah. Pyongyang, their heaven. On posters, in books, on banners, on television and the radio, father and son are omnipresent and omnipotent. These two patriarchal figures often appear side by side. They are portrayed as being the same age, they become timeless and similar, like one and the same divine icon. As I stand in front of their image, I no longer know if I am looking at them or they are looking at me.

I arrive in the capital, Pyongyang, "pleasant place” in Korean. “Heaven is here”: Han translates another sign for me. Shops and metro station exits are also christened “Heaven”. The regime views the capital as the perfect archetype of this Eden. It only remains to duplicate it throughout the country. Propaganda injects it into the countryside. The "farmer-comrades” have a duty to work hard in order to establish “heaven” where they live. And, in turn, the inhabitants of the capital are supposed to support the farmers during their “difficulties”, famines and floods.

The streets are clean. The people are disciplined. The children line up “naturally” in single file to get on board the school bus. The people are both spectators and actors. They act and look on, but only the leaders have the power to alter the setting. And, since we are in heaven, one celebration follows another. It’s official. The public always have a prominent presence so that they can applaud mechanically.

I still have the feeling of emptiness and fullness. A deserted boulevard. In a second, the square is filled with a crowd of young people. The choreography to the glory of the regime can commence: 200 red T-shirts and trousers dance and sing the praises of Kim Jung Il. Majorettes wave red flags. Suddenly, they all depart just as they have arrived. The square reverts to its empty, silent reality.

“Long live peace in the world!”, my guide blurts out, to fill in the silence. There’s something touching about him, but I get the feeling that he is troubled by anything that disturbs this wonderful equilibrium. He wants to convince me of the superiority of communism, Korean style. He frequently peppers our anodyne conversations with slogans. I get used to it. Nobody in the street speaks to me apart from my guide. Even when I’m on my own, no contact is made. Nobody seems to take any notice of me, everything happens as if I didn’t exist. Neither the police nor the army risk approaching me. Fear pervades us all.

On the bus, Han describes each building untiringly. Here you have the museum dedicated to the founding of the party. Over there, you have the bronze statue of Chollima. Elsewhere, the Liberation War Museum, an exhibition about the timeless exploits of Comrade Kim Il Sung: "This great leader drove back the invasion by the imperialist allied forces, for the country and its people..." Han always has an answer to my questions.

I have had to return there several times to realise that it’s all true. And that what is false is also true."

Photographer

Nicolas Righetti

Rezo

4 -

KASHMIRTerritorial conflicts—forgotten paradise. The war in Kashmir is probably one of the oldest territorial conflicts. Since the partition of India in 1947, it has seen the confrontation of Pakistan, India and Kashmiri separatist guerrilla movements. Photographs by

Marie Dorigny.

Dying at the front

Dying at the front "Even if the number of open or latent conflicts between states or within states is tending to decrease, we can still compile a register of critical situations. A by no means comprehensive list includes: Africa, between Ethiopia and Eritrea, between Chad and Sudan, between Congo and Rwanda; in Europe, in the southern regions of the former Yugoslavia and in Moldavia, in the Caucasus, between Russia and Georgia, between Armenia and Azerbaijan; in the Near East, between Israel, the Lebanon and Syria, as well as the Palestinian territories; in the Kurdish regions, between Turkey, Syria, Iraq and Iran; between Afghanistan and Pakistan; between India and Pakistan, between the two Koreas, between Japan and Russia, between Japan and China, not to mention the relations between China and Taiwan.

The war in Kashmir is no doubt one of the oldest territorial disputes. Since the partition of India in 1947, it has brought into conflict Pakistan, India and the pro-Kashmiri Indian guerrilla independence-seeking and separatist movements. The high valleys and mountains of Kashmir have been divided since 1949 by a cease-fire line, known as the LoC (or Line of Control), which is heavily militarised on both sides and the scene of recurrent bloody incidents and infiltrations. The conflict is also taking place on the Siachen glacier, which stands over 5,000 metres above sea level, near the Chinese border. Admittedly, as the result of the commotion caused by the earthquake in October 2005 (73,000 victims), the first bus route was opened between Srinagar and Muzzafarabad, which soon became accessible to lorries; four other routes are planned.

Attempts at a peace process between both states have been under way for at least two years, in order to improve economic exchanges, but commercial transactions between them account for less than 1% of their overall trade. The concept of a “soft border” has been put forward by the Indian side: not to change the actual borders but to make them free territory, by organising an Indo-Pakistani cooperation strategy in Kashmir, for instance as a condominium. For the time being, the only hope for the Kashmiri people lies in the pursuit of a “cold peace”. So it seems the blockade will last for some time to come."

Michel Foucher

Kashmir, the forgotten paradise "We have been visiting Kashmir for about 15 years: a region bloodstained by a conflict which has its origins in the birth of the two independent states of India and Pakistan in 1947. The border separating these countries has cut the region in two and divided the families on either side of what we refer to today as the “Line of Control”.

We quickly fell under the spell of this mythical region and it seemed to us that a simple journalistic report of bomb attacks and military operations, which attract reporters from all over the world, would be terribly reductive. We both felt that, in this valley, where death and pain are prevalent, there was another Kashmir, either dreamt or fantasy. It was within reach of anyone who knew how to recognise it. In order to do so, you only had to take the time to let the chance encounters and desires of the moment come into play.

Without us knowing it, we were following in the footsteps of two great writer- travellers of the 19th century, who were the first to describe, with wonder, the gentle beauty of the place and its inhabitants. The reflection of the foothills of the Himalayas in the waters of Dal Lake, and the ospreys swooping down at sunset. The call of the muezzins at dawn in the old town of Srinagar and the warmth of a cup of tea, placed into the hollow of the hands, while sitting on the steps of a Sufi shrine. The chatter of the women departing for the fields and the calm expression on the men’s faces as they gathered around a narghile. The straight-backed horsemen who accompanied the flocks of sheep, and the shawl draped over the shoulder of an old man. The delicate taste of saffron and cardamom too, with which they perfume tea and rice...

Thus, year after year, thinking we were blending softly into the intimacy of the Kashmir of legend, we let ourselves be possessed by its humanity, its spirit of tolerance and the splendour which demand respect."

Photographer

Marie Dorigny

Journalist

Marc Epstein

5 –

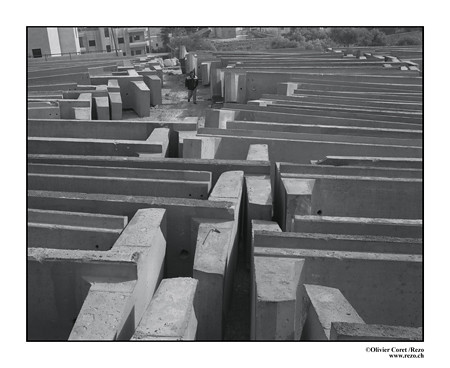

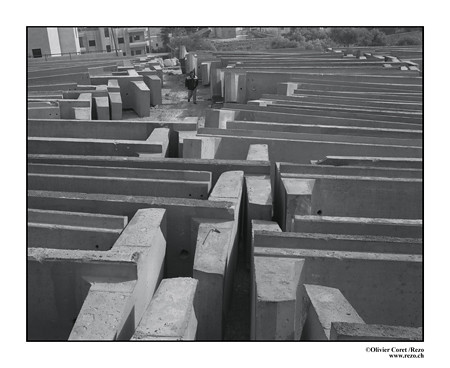

A BORDER IN THE MAKING: ISRAEL AND PALESTINEA unique case in the world of the physical formation, before our eyes, of a cement boundary, reinforced by passing places with sophisticated equipment, the prelude to a border between a state and an institution that aspires to statehood. Photographs by

Olivier Coret with the background sound from around the wall.

Borders that are neither safe nor recognised

Borders that are neither safe nor recognised "This is a unique case of the physical formation, before our eyes, of a concrete wall, reinforced by passing places fitted with sophisticated equipment, which is a prelude to the establishment of a border between a State and an entity which has the vocation to be a State.

The conflict between Israelis and Palestinians has a central territorial dimension: where and how to trace the border between both States from the time when the principle of the formation of a Palestinian State has been acquired? From 1948 to 1967, an armistice line – the green line – separated Israel from the West Bank. After 1967, the strategic border was moved to the River Jordan and the Golan Heights, and, according to law, the areas in between became the occupied territories where Israeli settlements were placed, but they were also home to three million Palestinians. This made it impossible for a Jewish majority to live permanently in a space to the west of the Jordan. Hence the acceptance of a Palestinian State by the Israelis. This option, which is also dictated by security concerns and breaches of trust between both societies, is expressed by the unilateral building of a wall separating Israel and the West Bank, and the return of the Gaza Strip to the Palestinian authorities. The wall doesn’t follow the green line but runs parallel to it, including settlement blocks and enclosed villages and, at its boundary, the Jerusalem conurbation, which is another point of contention. This wall is a barrier and border which can serve as the basis for a demarcation between two separate entities. As the Israeli geographer David Newman points out, it is not a wall between good neighbours: “first of all, we create the events on the ground and then we expect the whole world to align itself with the new situation”."

Michel Foucher

Life by the wall "Since the start of the second Intifada, I haven’t stopped travelling backwards and forwards between Europe and the Near East. The situation has got worse with each report I’ve filed. Six years ago, you could cross from Israel to Palestine without realising. Concrete blocks of particular colours at the side of the road indicated that we were entering one zone or another. And then there were the checkpoints, up to three of them on the 15 kilometres between Jerusalem and Ramallah. And these checkpoints were transformed into permanent structures, with barbed wire, watchtowers, endless security checks, random openings. It became a nightmare to move around. People’s lives were restricted.

Before beginning this report on the wall, I had stopped travelling to Israel. I couldn’t see the point of going to take a look and showing people over here what was going on over there. When I used to do reports on the Israelis, I was branded a Zionist. When I worked on reports about the families of the Palestinian kamikazes or Hamas, I was viewed by others as a pro-Palestinian militant. My work unintentionally fuelled the already established points of view, whereas I was working so that people would ask questions and feel empathy with mankind.

Building work on the wall began in 2003, and magazines published photos of the structure. They were beautiful photos, often showing panoramic views, with lovely colours. The wall was reduced to an aesthetic, cynical game. The role of photography came down to providing a graphic illustration of the subject. Because of this, I then decided to get back on the road to Jerusalem. I wanted to go and see people who were going to live with this wall and not the wall itself.

As I began working on this project, I expected that I would have to face dangerous, very violent situations, as is often the case in Palestine. However, over the course of a year, I’ve met with more resignation than rebellion, and that’s what has struck me the most. A people who have had themselves enclosed without even having the strength to rise up. I asked the inhabitants questions. They replied that they couldn’t do anything, not any more. I have never felt so useless but I carried on regardless. The Palestinians told me to stop, that these photos were of no use and I almost agreed with them. These photos are of no help, but they show how a border is created. I had wanted to condemn what was happening, but all I had done was to document history.

I feel the wall is part of the sense of history. For 50 years, the Israelis have been gaining ground, gaining space on this territory. This wall stops a border, it marks the end of an encroachment, and it may also be the beginning of a Palestinian State.

I would like to thank Beatrice Guelpa, Agnes de Gouvion Saint-Cyr and Jean- Francois Leroy for their unfailing support."

Photographer

Olivier Coret

6 –

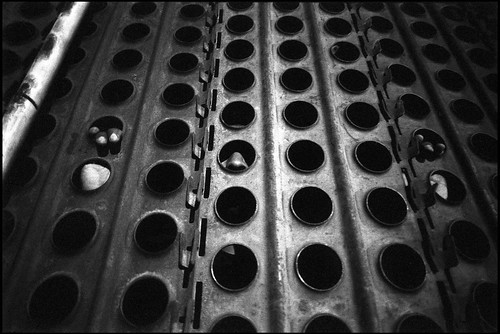

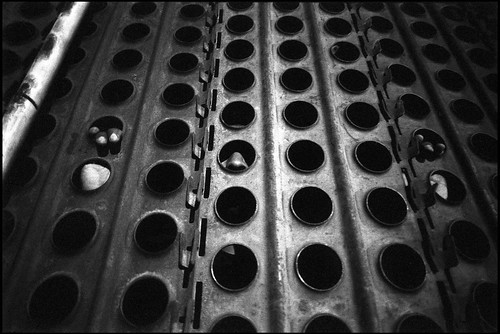

THE NORTH. THE US-MEXICO BORDERThe economic challenges of borders as a result of globalization. Unemployed Mexicans aspire to a better life on the other side of the border and American companies exploit cheap labour on both sides of the line. But this is an age in which differences between neighbouring societies generate migratory movements, which some people consider too large. And it is at this point that the border becomes a wall. Photographs by

Patrick Bard and screening of a film by the same author.

The grass is always greener on the other side

The grass is always greener on the other side "Are we on the brink of a world without borders? One border vanishes, and two others appear. It is as if man had an irresistible need to break up the world and to etch lines of fracture on the land between territories subjected to different rates of development. Borders remind us of the face of Medusa, whose gaze protects and attacks at the same time: they attract populations and businesses which seek to take advantage of difference, yet can end up preventing the much sought after contact and exchange.

The Mexico-US border illustrates this situation more and more clearly. Unemployed Mexicans aspire to a better life across the border and American businesses take advantage of cheap labour on both sides of the line. However, a time is approaching when the gap between neighbouring societies is engendering migratory movements which are deemed to be too large by some. And this is when the border becomes a wall. Two figures express the importance of this phenomenon: today, the US has a population of 20 million Hispanics; for ten years, the Mexico-US border, which is about to become another iron curtain, has seen the death of more than 3,000 people in search of a new homeland."

Henri Dorion

El Norte "El Norte. The border separating the United States of America from the United States of Mexico is some 3,200 km long, and stretches from the Atlantic to the Pacific. News reports frequently put the spotlight on the immigration problems that crystallise there. The NAFTA accords, which allow the free movement of goods between Mexico, the USA and Canada, came into effect at the end of 1994, at the same time as Operation Gatekeeper. The latter focused on stepping up border patrols in order to stem the flow of illegal immigration from Mexico and Latin America: the building of a wall which is a material representation of the border in all urban areas, an increase in personnel, an ultra-sophisticated surveillance and detection system. The America-Mexico border is the world’s most frequently crossed line, both legally and illegally; it represents an important economic wager. Even more so if we consider that it is the longest shared border between an emerging country and a rich country. The richest country in the world. A place where everything, or nearly everything, is enlarged as if under a magnifying glass, on a continental scale. George W. Bush recently stated his intention to send 6,000 soldiers from the National Guard to the border. At the same time, the US president announced the regularisation of several million migrants. Contradictions of a country that cannot do without cheap labour and has to pander to its most conservative wing, who are concerned about the 30 to 40 million Spanish speakers who live in the USA.

A low-intensity zone of conflict for the Pentagon, an economic laboratory for globalisation, a place of economic and social violence, the object of all kinds of peripatetic industries, the US-Mexico border is an obstacle for migrants who aspire to a binational vocation. However, the border is also a third country, between Mexico and the USA: an “Amexica” where two nations, two cultures, two peoples are summoned to meet, in a state of chaos, no matter how high the walls."

Photographer

Patrick Bard

7 –

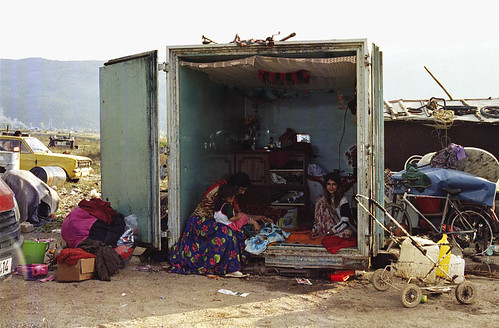

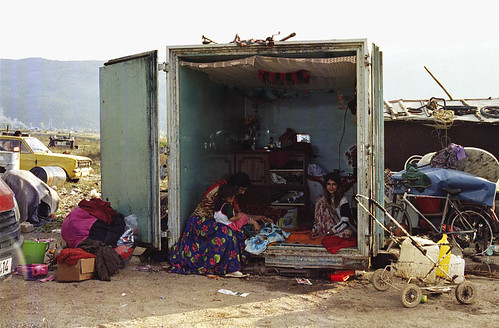

REAL CHRONICLES OF AN IMAGINARY COUNTRYThe world of landless peoples: gypsies scattered throughout Europe. Photographs by

Éric Roux-Fontaine.

Scattered throughout Europe

Scattered throughout Europe "We know about the sad fate of the so-called landless nations. But are they deprived of borders because of this? Doesn’t the juxtaposition, without osmosis, of societies rooted in their territories and scattered societies, underline the fact that the sedentary world imposes its social, economic, anthropological and cultural borders on its transient neighbours? Others will say that the travelling population carry with them in their meagre luggage their community borders, which mark out ephemeral territories, at each stage of their journey.

These are two contemporary realities which turn their backs on one another by drawing on their origins in different times and contexts: on the one hand, a sedentary world which is modelled on the new mobility codes stemming from globalisation and, on the other, a world which, for centuries, has taken its roots and identity from what is perceived as an eternal wandering. Could this exclusion be responsible for the astonishing vitality of these flexible societies? Because we can say that these societies, of which the Roma are a classic example, are protected, to a certain extent, by the invisible borders which surround them and follow them on their journeys: borders that are just as invisible as their territories."

Henri Dorion

Rromano than "When asked, “What does being a Romany mean to you?”... the man answered me, “It means living here, or anywhere else on earth, and knowing that, whatever happens, no government will stand up for us ...”

This prompted me to follow the journeys taken by these families, who have to juggle endlessly with requests for asylum, notifications of expulsion, and forced repatriation. Month after month, I encountered friends in Sarajevo who I had met in Vaulx-en-Velin, when they would come knocking at my door, and other families who had been “escorted” out of the country by the border police some time earlier, who paid me a short visit before setting off again in secret for England or Montenegro.

Rromano than is the result of “geopoetical” wanderings through a country that nobody ever reaches. A journey through travel, to meet the Europeans who are exiled in Europe, to meet a landless nation.

The photographic project was carried out over a period of about four years, mainly in France, Romania, Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina and India, the historic country of departure for those who would later be called Manus, Roma, Kalderas, or Sinti."

Photographer

Eric Roux-Fontaine

8 -

EXILEPermeable and hard borders: the exile of refugees. Photographs by

Michel Séméniako.

Exiles and refuges

Exiles and refuges"Borders break up time and space in equal measure. Initially, they are lines, either imposed or agreed, which mark out a more or less watertight solution of continuity between the territories where the candidates for voluntary exile hope to make their new homes, and those which impose on them living conditions that are deemed to be unacceptable and which they seek to leave. This line also marks out long periods of time: the time of waiting to travel to a second life and then, after the crossing, the time of the expected welcome, of a job, of inclusion. But the border is often a purveyor of illusions. The image of a better world beyond the line holds an attraction which doesn’t always keep its promise.

Getting past the border guards is no guarantee that you have made it. Once crossed, a new version of the border can weigh heavily on the shoulders of these travellers for a long time. Solidarity between refugees often shows itself in the shadow of the factories or blind walls, much more so than inside these worlds which are often closed to them. Nevertheless, borders spring up there too: the taggers also need to mark their territory 19 which they feel is under threat or to make their presence felt in other people’s territory. But would physical borders, no matter how much barbed wire they contain, be less watertight than social borders?"

Henri Dorion

Exile1/"One day in the year 2000, I came across the spectral, greenish image of a group of illegal immigrants in the press. It distressed me deeply.

A hitherto buried family memory, as fragmented and disorderly as a graveyard, was suddenly reactivated by the news.

This image of human beings, hunted down like wild animals by heat-seeking cameras, expressed the overriding violence of the powerful, equipped with sophisticated technology, on the poor unfortunates who are fleeing war and poverty. By using infrared film, I divert this “cold” surveillance technique. I invert the process: heat no longer outlines a target, but expresses the aura of living bodies, their energy to survive.

The close links which connect recent dramatic events (Sangatte, people without papers, the Mediterranean boat people) with my family memories have given rise to this project.

The origin of migrants has always marked out the map of conflicts and poverty in the world.

There is no other way out for illegals other than to break away from their family, material and cultural roots: their flight forces them to hide their uniqueness to the point of invisibility. They incorporate this obliteration as a condition for their survival and their exile takes the shape of a dream-nightmare.

The denial of the past wreaks havoc. This questioning, which touches on memory, history and the sources of artistic creation, runs through Louise L. Lambrichs’ literary work. Her texts, which were written to accompany my photographs, trigger a dialogue with them and generate a realistic fiction. Spoken writing, an inner dialogue as if in suspense, links the character-images to the reader and imbues my stray ghosts with vibrant humanity."

Michel Semeniako, summer 2004

2/ "Exiled in their history or language, foreigners in their own land, isn’t it the writers who always start with a point of view from which they seek 20 to make understood what cannot be seen? From this point, they question the world, clarify, shine forth, have encounters, connect with others.

Michel Semeniako’s work on exile, at the time when I had just completed We will never see Vukovar, awoke familiar voices in me. Doubtless because I myself had just relived the same story, – the story he told from his own origins – by other paths."

Photographer

Michel Semeniako

Writer

Louise L. Lambrichs

9 -

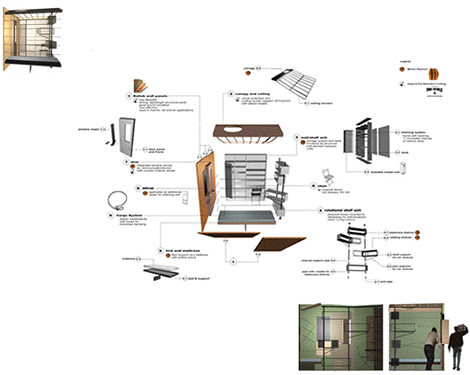

OCEANMALECONDRIVEAn

installation designed by Enric Massip and Ángel Morúa contrasts the seafronts of Havana’s Malecón and Ocean Drive, Miami Beach, forming a “border street”.

OCEANMALECONDRIVE TRANSATLANTIC STREET: BORDER STREET

OCEANMALECONDRIVE TRANSATLANTIC STREET: BORDER STREET "OceanMaleconDrive is a new category of urban planning, comprising two linear, sea-facing faccades, separated by 300 kilometres of ocean. Two faccades, the Malecon in Havana, and Ocean Drive in Miami Beach, which are, in turn, the urban icons of their cities, their paradigmatic images.

And each side of the street has its own neighbours, who despite facing the difficulties of a border in order to cross the 300 kilometres of liquid road, think about their neighbours across the way, neighbours they dream of but can’t see. So, the inhabitants of Havana lean out of their windows or sit on Antonio Maceo Avenue to talk and dream about life on the other side. Meanwhile, on the other side, their neighbours sit on the terraces in front of Lummus Park to imagine their lives over there, a return or a visit made possible just by crossing the road.

But this street already existed at the beginning of the 20th century, although then it was a physical not an emotional border. And the way of crossing it has changed over the years, depending on where Paradise or the Enemy are. Perceptions of each of the two Cities, of each of the two Worlds.

The 300-kilometre wide street, shaped from the feelings of its neighbours, seems to be the ideal setting for building OceanMaleconDrive."

Angel Morua and Enric Massip-Bosch

10 -

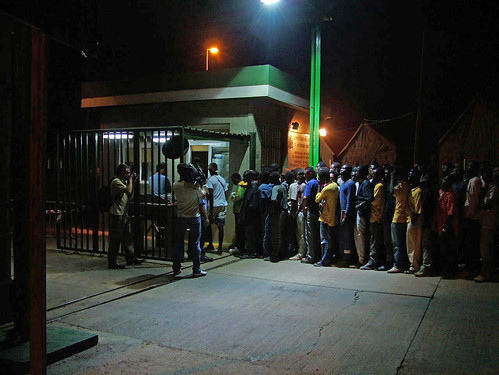

MELILLAThe fence in Melilla: three successive rows of wire fencing. The tallest is seven metres high. On one side, the Moroccan army controls the perimeter, on the other lies the sea of wildest dreams. Beyond the fence, on the outskirts of the cities of Morocco and Algeria, improvised camps hide people who, one day, set out on a journey in search of a decent life.

Europe: an island?

Europe: an island? "Heaven lies behind a fence. For many years, Berlin divided Europe in two. Its wall enshrines the tragic memory of the thousands of people who tried to jump it, always in the same direction. Today it is just an icon, but then it was a border and a metaphor for two worlds: heaven and hell. Everything hidden on the other side was suspect and uncertain. And although the wall finally fell, the idea behind its existence is still prevalent today. It seemed there were no walls left in Europe, yet what form of short-sightedness can overlook the 12-kilometre fence in Melilla? The world hasn’t changed so much when it is able to maintain a deep divide between those who enjoy it, with all their rights, and those who are condemned to view it from the barrier.

This fence, which also separates two worlds, represents the imposed and compulsory repetition of ideas that have proved to be archaic. However, its aesthetic instils fear and the barrier is real. There are three successive rows of wire fencing, the highest standing 7 metres. Between them, a labyrinth of cables and barbed wire has been designed to destroy, one by one, all the parts of the human body. On one side, the Moroccan army patrols the perimeter and shoots to kill, and on the other side, lies the land of milk and honey. Does the fence serve any purpose? Its presence is so imposing that, every day, it prevents us from seeing the bodies being torn apart. However, the problem it is trying to halt hasn’t disappeared, it has just moved a little further away, towards a place in silence. Does anybody think they can stop immigrants coming in? Immigration continues, at a slow and constant pace, despite border closures, because there is no hope of change, in the near future, in most of the countries the immigrants come from.

The fence is certainly impressive, but what it tries to conceal is even more so. A reality as overwhelming as its height. Its presence has fostered the development of real human traffic networks which use the closure of borders as a resource. These networks now decide the fate of the thousands of stateless people with no papers, and no income, who, one day, set off on a journey in search of a decent life and are now hiding in makeshift camps on the outskirts of cities in Morocco and Algeria. Some have been in this situation for years. The journey to the European dream is a journey with no way back. They have no alternative: they will reach Europe or die. Today, their body is the only border that separates them from heaven. Nobody stands up for them and, what is even worse, in the limbo they occupy, nobody feels compelled to do so. They are so far removed from the European conscience that they can wander until they vanish, without us even being aware. We know they exist, but our watertight society doesn’t want uncertainties. The fence thus becomes a way of alleviating collective responsibility: those on the other side don’t matter to us, their drama no longer has anything to do with us. They are shipwrecked people, outside the island. Our main concern, on this side of the fence, is to know how long we can remain cut off from them."

Rafael Vila San Juan

11 -

Audiovisual installation with original work and artistic direction by Frederic Amat. Produced on the basis of the lectures given as part of the “Borders” cycle, which took place at the CCCB from 12 January and 29 March 2004 in the framework of the 7th Barcelona Debate, with the participation of the following speakers: Roger Bartra, Zygmunt Bauman, Georges Corm, Manuel Cruz, Francisco Fernández Buey, Michel Foucher, David S. Landes, Tzvetan Todorov and

Eyal Weizman.