Snake Tunnels in Taliban Territory

[Image: Traveling Into Taliban Territory, 60 Minutes, 2009.]

Recently, Steve Kroft of 60 Minutes took a tour of Taliban Territory on the border of Pakistan and Afghanistan and, among his stops, was led to Bajaur, “a tribal agency adjacent to Afghanistan's violent Kunar Province,” we are told, “and the site of a brutal fight between the Pakistani military and the Taliban last fall.”

There, Kroft was escorted to a captured Taliban compound ten miles from the Afghan border where he got to dip his toes into a “maze of tunnels” the militants had dug out over the course of several years, that he is told are connected by at least a mile (if I heard the video correctly).

[Image: Traveling Into Taliban Territory, 60 Minutes, 2009.]

Quoting producer Draggan Mihailovich from the online version of the piece, “Stepping down into the first tunnel, it quickly became apparent the Taliban fighters didn’t suffer from claustrophobia. The entrance was snug. But the outlets which led to other rooms, bunkers and compounds under the ground looked like they had been built for snakes. The Taliban had to crawl on their stomachs for hundreds of meters to reach these rooms and bunkers.”

Kroft produced a short video viewable here.

But, unfortunately as you can see he obviously didn’t sink down too far into his underworld adventure, and so the footage really only shows the first few steps that lead toward another mouth, which supposedly connects an entire complex of passages beneath the compound. Though, if belly crawling is required, I guess we can cut old Kroft some slack.

It’s hardly a startling find – I am just surprised we haven’t gotten to see inside more of them as time’s gone on. My favorite line in the piece: (Kroft): "Are you sure it's safe to go in here?" ... (Pakistani commander): "Yeah sure, why not?"

With that, I’m reminded of a good post Geoff put together over two years ago now, surveying the geological history of Afghanistan (one of the most mountainous countries in the world), which has to some degree – alongside the climates and engineering feats that have whittled the nation’s past – given way to an entire legacy of natural caves and excavations, irrigation networks, secret tunnels and bunkers, ancient hollowed forts and compounds, and plenty of other staggered burrows and buried hideouts that have served everyone over the years from Afghan’s own people during the days of Atilla the Hun to Osama bin Laden and his marvelously elusive cronies, to a range of arid high-altitude farmers, herders, regional traders, nomadic mystics and expelled refugees, all the way to good old John Walker Lindh (remember the “American Taliban”?...according to this report he “took cover in an underground tunnel” with the Taliban in Mazar-I-Sharif, and “stayed there for 10 days, despite no food and repeated attempts to force them out. Coalition troops started fires in the tunnel and even tried gas, but to no avail. They finally rooted the extremists out by forcing water down the hole and filling it up.”).

Certainly, we won’t fail to mention the many other key players who have taken refuge in the chunky outback of this region in more recent history, from the Soviet Union to the CIA, the mujahideen, the Afghan Northern Alliance, innumerable tribal warlords and common folk, the U.S. military, and last but not least, the Taliban itself (who, even when detained dug an incredible escape tunnel in order to break out of a Kandahar prison back in 2003)….whomever else one can only speculate –

[Oh, wait, there is one other – in recent news apparently a Chinese engineer who had been captured by the Taliban and held captive for many months in an underground chamber, has just recently been released. As it turned out, since the Taliban didn’t want to keep exposing him to the outdoor surface area while taking him to the bathroom, they apparently dug a tunnel for him that led straight from his chamber to the bathroom to avoid the risk of his being able to see his surroundings and plan an escape. Yet, being the tunnelers the Taliban are, I am surprised they gave him even the idea of a tunnel.]

[Image: The Hunt for bin Laden - Tora Bora | The Guardian.]

Nevertheless, as a military fossil, Afghanistan is an epic imprint of human history’s ongoing engagement with the densest contours of the terrestrial, where ancient culture has been embedded in the geologic timescales of conflict space for centuries. The country’s story could probably be entirely retold in the evolutionary compressions and picture carvings of its vast mineral deposits alone. If Afghanistan were a book, its pages would be composed of ancient lithic space, there would be chapters on mythological caves, karezi canals and the more egregious military archeology of centuries worth of warfare. Dust-bound stories captured in the petrified pages of Asian history, cultural memories scrawled in open a closed fissures; a complete archive of Afghanistan’s struggles with itself and its neighbors stacked upon one another in alternating layers of sediment violence and mineralized calm.

Despite’s Afghanistan’s unfathomable weight in rock and stone one can only be as intrigued by the kind of aerated voidspace dimensions that harbor within it; for all that is topographically observable in the rugged mountain ranges on the surface that give Afghanistan a look of disgruntled geographic muscularity, there is behind it all the skeletal chasm-works of an immeasurable hollowscape that is irresistibly mysterious, and has also lent a kind of cultural imaginary to Afghanistan as this far off haven of sorts for those to escape the imperial reach of the U.S.’ military strong arm.

Opinions abound, but has Afghanistan come to represent the final frontier for empire – the endgame? Is it that resilient edge space where landscape is yet again the greatest enemy to the world’s single military superpower? Where empire’s chief nemesis apparently drops off the face of the planet and disappears without a trace?

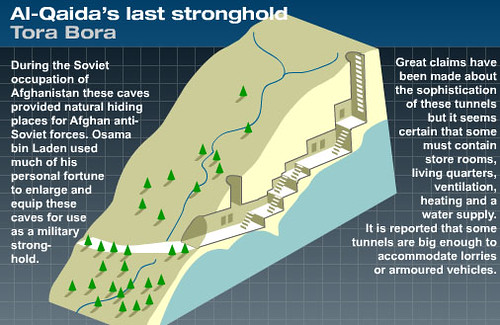

After the American Air Force bombed (nuked) the you-know-what out of the Tora Bora mountains following 9/11 where bin Laden was allegedly hiding deep in the intestinal fortitude of Afghanistan’s geological bunkerlandia, where my friend’s mother who lived in Iran at the time claimed to be able to hear and even feel the earth pounding from miles and miles and away; and where a string of earthquakes were not only triggered inside the mountains but were set off by the bombing and reported to have been felt as far away as India, the Tora Bora mountains became a crude geographic symbol for a kind of insurmountable extremist resistance (the military might of the Soviet Union was defeated there, so why wouldn’t the U.S.?).

Somehow, not only did bin Laden escape, but even after the U.S. waged its most relentless multi-ton bunker-busting bombing campaign capable that decapitated entire mountain tops, the tunnels and complex cave networks seemed to have stood to a very large extent in tact. Which, as Geoff’s piece points out, is a testament to the incredible geological formations that have encrusted the surface there over thousands of years with some of the most solid and indestructible rock found on the planet – in some sense the ideal landscape for surviving nuclear attack.

But, to quote Sobhi al-Zobaidi:

“Beyond the geographical designation for a location in the White Mountains in Eastern Afghanistan, the term Tora Bora has become synonymous with some sort of a spatial maze, a web of underground tunnels where someone (like Osama bin Laden) can hide and disappear. In the media as well as in public imagination, Tora Bora has come to mean a new kind of territory, interior territory that cannot be mapped or fully revealed or exposed and whose elusiveness gives rise to ever more fantastical imaginings.”

In other words, Tora Bora, (but perhaps Afghanistan more generally speaking now) has become a kind of mythical vortex for U.S. evasion; a geological black hole that only the local militias know how to navigate, that provides the empire’s most wanted with limitless and unknowable realms of bomb proof sanctuary.

Especially now, as the prospects for American conquest in Afghanistan look less and less certain, the region is beginning to look like the ultimate counter-empire landscape – a combination of geology, ancient engineering, indigenous knowledge of the landscape, and corresponding ad-hoc war tactic that seems to make for the perfect strategy to defeat foreign occupation. In fact, how many times do we need to see similar examples of subterranean resistance work? Much like Israel’s recent bombing campaign of Gaza failed to destroy the intense tunnel network along Egypt’s border, is underground Afghanistan the final frontier in the U.S.’s “War on Terror”?

[Image: A mountain tunnel in Zabul Province, Afghanistan, via Afghan tunnels prove tough to crack2007.]

I was reading an article about a group of American soldiers who were combing the Afghanistan countryside to clear tunnel and cave networks, when they come upon this one series of caves that the locals had told them repeatedly was only used to store hay and had nothing to do with the Taliban. The soldiers refused to accept this and set up blocks of C4 and grenades along the cave mouth in attempt to cave it in and make the tunnel inaccessible. Of course, their detonations miserably failed and all they were left with were plumes of dust and the explosive stench of military futility. In the words of the commanding officer at the time, “It’s moments like this that you have to laugh,” [he] said. “We gave it everything we had and didn’t make a dent. Now we have to go back and tell the villagers, ‘OK, you can have your cave back.’”

There is something so simply revealing in this story to me; not only is there a lesson of ignorance and embarrassing defeat, but it’s the tunnel that will last, it’s the tunnel that always has, it’s the tunnel that will continue despite any sort of military operation brought against it, because the tunnel in this case is nature itself – like many tunnels which are a natural response to superpower, to border siege, or violent colonization. It is, despite its earthen barriers, pure liquid, running and doglegging in any direction it needs to, seeping as low as it must, around anything in its path, to find oxygen on the other side, to push its flows of wind and water, or economy and migration where the gravities of geological or geopolitical pull will deliver it.

We see it over an over again, the tunnel as the perpetual thorn in military superpower’s side. It crops up where empire is not looking, and then even in the face of overwhelming authority it pushes through and succeeds still undetected well below the technological prowess of the state. Over and over again we see it is the tunnel that manages to survive. And that alone – that a single spatial form could persist even in today’s military climate – is just unbelievably fascinating to me.

I’ll be picking up more on this in the future, the underground resiliency of places from Gaza to Nogales, Kowloon to Baghdad, Lebanon, Canada, just to name a few; the tunnel as the raw liquid-space of superpower’s subversion, globalization’s Achilles heal, this perennial undoing of the colonial landscape, etc.

Related Readings:

Inside the Tora Bora Caves By Matthew Forney Tuesday, Dec. 11, 2001 | TIME

A NATION CHALLENGED: CAVES AND TUNNELS; Heavily Fortified 'Ant Farms' Deter bin Laden's Pursuers By MICHAEL WINES, November 26, 2001 | New York Times

A NATION CHALLENGED: GEOLOGY; Nature Made The Perfect Hiding Place By KENNETH CHANG, November 26, 2001 | New York Times

Escape from Tora Bora, 4 September 2002 | Guardian

The Hunt for bin Laden - Tora Bora | The Guardian

3 Comments:

My initial response to this post comes in the form of the irony associated with the worlds most technologically advanced military force being defeated by the alliance that has formed between a primitive guerrilla military troop and landscape. I don’t know which is a more crowning achievement, America developing the technology to create bunker busting missiles that can be fired and controlled with pin-point precision, or the Taliban rendering the technology useless through inhabiting their landscape? I find it intriguing how the international fight between capitalism and terrorism has, in Afghanistan, been reduced to a duel between technology and sustainability. It wasn’t tear gas, bombs, armed assault, or food deprivation that forced John Walker Lindh and others to flee from an underground stronghold. Thousands of gallons of water had to be pumped into the caves to have the men flooded out. The parts of this post that I would like to dig deeper into are the architectural implications affiliated with underground tunnels combating modern technology. What were the basic architectural principles that Attila the Hun followed in early establishments of mountain caves? More importantly, why were these principles of environmental habitat lost or misunderstood in western societies’ advancements? In regards to architectural evolution, the caves offer insight to the complex meaning of interior space. Architects have always dealt with spatial projects in terms of interior versus exterior space. But what can we architects make of a community existing purely at an interior level? Not only are the Taliban fighters challenging western democratic thought, but apparently they are now angry western architectural principles as well. In the upcoming quest for sustainable development strategies, it is essential for innovative thinkers to consider the obvious advantages to subterranean climates that have been found in Afghanistan.

it might be too late to ask this question, looking at the date of the post, but after all the subterranean posts you made, i couldn't help but wonder why haven't you mentioned chu chi tunnel in vietnam?

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cu_Chi_Tunnels

just want to know your reasons. keep inspiring + inspired.

I am glad that you quote my text in this interesting piece. but I thought that it is a good idea to mention the source for the quote, which is

jump cut. no. 50, spring 2008

thanks

sobhi al-zobaidi

Post a Comment

<< Home