[Image: US-Mexico Border Fence at Imperial Beach, California. Photo by Bryan Finoki, 2007.]

[Image: US-Mexico Border Fence at Imperial Beach, California. Photo by Bryan Finoki, 2007.]It certainly isn’t new to discuss anything these days in terms of

fluidity and

flow, perhaps least of all global migration. From academic daydreamers intoxicated with Deleuze to mundane AP writers simply reporting the news, the

floods of migrants, the

deluge of border crossers, and the

waves of refugees, seem like common phrases in most of the discourse on migration. It’s almost the vernacular it seems to compare the movements of refugees to oceanic tides, or, chaotic rivers, desperate inundations, masses crashing on the shores of statehood’s rejection, seeping past the gates towards the doorsteps of a surrogate homeland. Just as unstagnant water exists in a state of constant motion, human migration, too, presses on in its own state of permanent unsettlement, in its own form of hyper-alluviality, I suppose, wandering in all directions and dimensions – like global capital personified, or something.

Migration, as a space, could be viewed as a kind of restricted amorphousness, at times sprawling and others dammed, refunneled, overflowing, boring under the earth, tendriled and uncontained, evaporative, invisible. The refugee is bound in perpetuity between here and there, place and non-place, legal and illegal, formal and informal, stable and destable, entitlement and undocumented, inclusion and exile – politically speaking, maybe a state of non-being.

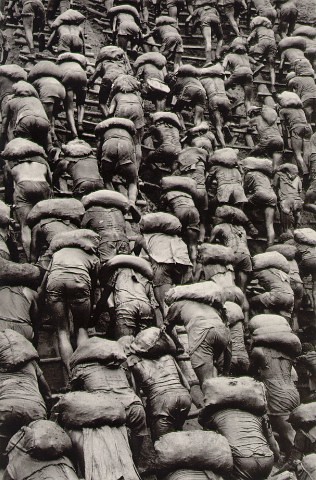

Now, I’m certainly no expert on migration, refugees, biopolitics, or anything for that matter really, but you’ve heard the term ‘floating population’ in reference to China’s roughly 150 million temporary workers who have flocked from the countryside to the urban cores that emerged in the last 15 years of economic boom, as China largely shifted from an agrarian based economy to becoming a global industrial powerhouse. In a much

earlier post on

Subtopia, learning of this phenomenon, I wondered whether “floating population” could be a useful term to describe a much larger cumulative global populace that’s similarly reorganized by new spaces of borderless capitalism and nomadicism.

What are we to make of the colossal dispersal of migrant workers flitting about the planet today sans papers but still wherever labor will have them? Or the mass exodus of refugees fleeing the war torn landscapes in the Middle East? Aren’t many of the seas of imperiled asylum seekers from Africa just victims of obscene wealth distribution? And aren’t thousands if not millions of other displaced victims of climate change and natural disaster partially wayward extensions of a fundamental global failure to respond to crisis beyond the crimes of disaster capitalism? Add to this the goliath flock of a billion plus squatters covering the hillsides and settling into the cracks, and an alarmingly swollen body of urban homeless that helps expose the vaporization of a global middle class, as well as an inexact crowd of detained immigrants lingering in the face of uncertainty, one might think the goal of globalization was to devise a massive deportation system for banishing its leftover people to a life of suspended captivity netted beyond any evolutionary reach of citizenship, legal, socio-economic, or humanitarian responsibility.

It seems one way or another a growing majority of the world’s people are becoming geoeconomically uprooted and caught in between two parallels of opposing nowheres: a past place of expulsion, and a future one of denial. Remaining, is an empire of serfs left to percolate on the outskirts of power and along the edges of nationality, clinging to the fringes of extraterritoriality that surround the mouth of a property, economic, and juridical abyss, eager to render them something akin to

superfluous.

Please forgive my obscene pretentiousness and lack of historic understanding here with all of this (the act of

Subtopia is more than anything a learning process), but migration might be seen as a kind of atlas of spilt geographies intermixing different nomadic movements and subcontinental rushes with other lesser seen drainages of idigens and trajectories of assorted exodus, stirred by the constant exigent flows of industrial displacement that flush a niche in everything straddling the border at the push and pull of different political and economic gravities. It is the terrain of both flood and its desiccated aftermath; ravines in the form of footprints, shorebreak as a broken human animation.

I don’t know, that probably made very little sense, but as a geographic phenomenon I guess I sort of visualize migration as these overlapping threads of tracks that all lead back to some kind of city that never was, an origin of statehood perhaps, assembling itself for the first time under its feet as it moves its parts steadily forward - but in reverse – along an unraveling periphery, resting its temporary structures in crevices designated only for unrest and arrest; sort of like an unkept civilization stranded over various fault lines of geopolitical instability; or, a dispersed race sloshing and trickling along the edges of disaster, permanently rutted in the failures of crisis response. On one hand it’s an abstract geography of biopolitical buoyancy filling in the gaps of spatial fallout and resisting any real or official boundary; on the other hand, it’s the survey of an escape from a dubious sovereignty that manages to assert itself beyond its own formal territory.

Certainly, my practice at mumbo jumbo has done very little to clarify anything, I know, but, visualizing all of the movements of migrants through a transparent three dimensional model of the world (something I would love to see), I imagine it would look like a bruised piece of fruit encrusted with subdermal hyper capillaries coursing with humanity in liquid form, or some sort of arterial system passing acid through the earth’s most hardened structures; basically, a self-modifying irrigation subtopia pushing unstoppable fluid past, around, and through anything in its path; migration as the undeniable power of fluidity in its rawest state.

Anyway, I used this analogy much less clumsily in a chapter I’ve written for a forthcoming publication (which I will mention more in the future), and in part put it more clearly like this:

To look at the migration paths fingering upwards from Africa towards Europe, (like the Trans-Saharan migration zone, for example), or the sea voyages along the coastal peripheries of Spain and throughout the Mediterranean Sea, or the veins of movement that tendril northbound from South America up through Mexico to eventually split in multiple fractions across the US/Mexico border—we cannot help but draw comparisons to the great alluvial landscape patterns of the world’s riverbeds and streams and long winding natural water movements that have contoured the planet’s topography for centuries. Metaphorically speaking, the refugee is ultimately the captive of a kind of mock-hydrologic system of exclusion and containment—a military hydrology of border control—where national peripheries no longer spill into one another but become more hardened by structures of institutionalized violence and friction.

It’s what I’ve been theoretically developing as this

nomadic fortress – migration enforcement in terms of an unprecedented engineering project; or, the border fence as kind of sprawling universal super levee.

But certainly, people aren’t floods; and perhaps, like floods, mere walls cannot contain them. Nor should migrants be treated with equivalent barriers of borderland floodgates and levees. In some ways, I wonder, how the discursive use of the flood/migration analogy might only contribute to the acceptance of a political logic that assumes migration can somehow be managed in much the same way as broken and overflowing hydrology. I wish I had a few quotes here to provide of enforcement agencies framing migration in terms of a hydrological problem, but I don’t at the moment.

Nevertheless, my purpose here is less to try and argue the merits – or lack of – using

fluidity as a productive metaphor, but (after all this excessive verbiage) just to show a few examples of how issues of “illegal” immigration, national security, and active floodplain control are very literally – and very eerily – being handled together in the U.S. government’s attempts to “secure” the Mexican border.

Where once the government may have been able to boast progressive environmental conservation, we now seem to be getting a strange experiment in

security preserves instead. Not security measures designed to protect the environment, but environmental augmentations that might be meant to protect the security measures themselves.

Migrants from the south have always shared a precarious relationship with the U.S., and have generally been welcomed and recruited during times of economic prosperity, while they’ve been demonized and pumped out when the economy has deflated. These pools of workers have been treated like a kind of exploitable neighboring aquifer; labor that could be siphoned in and out of the U.S. from Mexico through less obvious but well-worn aqueducts for decades to service American industry. Now, with the current political climate and the economy shriveling, the perception seems hardly any different of the migrant workers as half-starved invaders seeking to take jobs and food and services away from the American family, and as dead weight on America’s back – except now they’re being treated as cultural pollutants, as a rising level of economic wastewater, and, even as slippery mock-terrorists. Not only does the Department of Homeland Security view this intractable onslaught of Latin migration as a hazardous drenching of their preciously kept backyard lawn, but as a colossal breach in the border integrity of its glorified sovereignty, long un-walled, now paving the way for subversive avenues of jihadist infiltration, or for narco-insurgency networks seeking to usurp power in the southern states.

The metaphor of fluidity tempts reflection on migration to fall onto a de-soveriegnating axis, one that is irrespective of borders, and, potentially, inherently threatening to the social and political landscape of nationalism. I wonder, is it just a fundamental flaw of the U.S., and the world for that matter, to not be able to comprehend migration as a beneficial flow, one that can help reinforce national identity rather than deteriorate it?

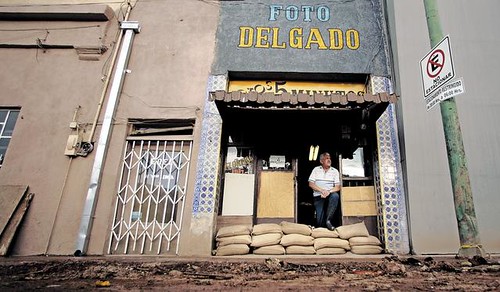

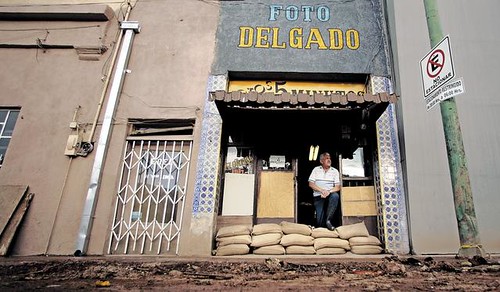

[Image: Brownsville/Matemoros, Texas/Mexico border. (source)]

[Image: Brownsville/Matemoros, Texas/Mexico border. (source)]Nevertheless, the political response distinctions between immigration enforcement, security planning, and flood control are breaking down like fat turds in the rain only to be reconstituted together in a twisted weave of concrete, rebar, and metal grating along numerous “floodzones” near the border.

First, let me remind you of Nogales where Arizona and Sonora, Mexico share a massive sewage infrastructure that is used regularly for both flood mitigation and border crossers. I’ve mentioned these

Orwellian Wormholes before where the U.S. Border Patrol has entrenched itself deep within the concrete bowels of the earth, with a special Tunnel Task Force to prevent the dark dank halls below the border from serving as an “underground superhighway” for coyotes and smugglers, as Richard Marosi put it in the

LA Times.

However, it’s monsoon season in the desert and

heavy downpours recently

flogged Nogales, so much that the

Nogales Wash backed up considerably and caused devastating flooding along the border. 50 stores in Arizona were damaged, while several

colonias on the Mexican side were practically washed away. During a recent

downpour a few bodies were flushed out of the underground like debris loosened from the mouth of a gutter, while several others were later

rescued. Absolutely, a total mess.

To try and make a long update short, Santa Cruz County declared a state of emergency, and

millions of dollars will be needed to clean up and repair large sinkholes that sprang up right alongside the border fence to salvage businesses, and to rethink ways of avoiding this scenario in the future.

[Image: One local storm watcher even captured a photograph of a funnel or tornado cloud from her Nogales, Ariz., home about one mile from the border. (source)]

[Image: One local storm watcher even captured a photograph of a funnel or tornado cloud from her Nogales, Ariz., home about one mile from the border. (source)]But,

what caused the flooding? Granted, the Nogales Wash is 75 years old and from what little I know pretty run down, but it has handled this type of irrigation for decades in the past, so why did one underground tunnel back up so severely with water and cause all of this flooding? Well, it wasn’t a clog of bodies or debris, if that’s what you were thinking, thank goodness.

As it turns out, back in February the Border Patrol built

a wall inside one of the main tunnels that crosses the border to support a floodgate that they claim was routinely sabotaged by smugglers in attempt to discourage them from continuing to pass through. This was done apparently without the approval of the International Boundary and Water Commission, and

preliminary surveys suggest that the construction of this inner-tunnel border wall was responsible for at least 40% of the flooding that occurred July 12th. Mexico recently

filed a complaint demanding the U.S. to cover the cost of the damages done on the Mexico side, even though this initial survey also seemed to indicate that some added piping inside the tunnel on the Mexican side may have also contributed to the flooding. “The tunnel, built in the 1930s, is a 20-foot-wide rectangular concrete conduit that ranges between 11 and 18 feet tall”, this

source tells us.

To further exacerbate the situation, there are concerns that the Border Patrol’s wall wasn’t merely

built on the somewhat ambiguous boundary line inside the tunnel (marked by a faint yellow line), but was actually

constructed partially on the Mexican side of the border underground.

The wall runs perpendicular to a steel floodgate in the Nogales Wash tunnel and caused water to back up during the July 12 storm, according to officials of the Mexico Section of the International Water and Boundary Commission. Then, they allege, the pressure blew out a portion of the tunnel ceiling, flooding Calle Elias and Calle Internacional.

The resulting deluge was retained by a decorative border wall, and about five feet of water pooled in the area. It damaged several buildings and vehicles. Eventually the water burst onto Morley Avenue in Nogales, Ariz., where more than 50 stores were flooded. (source)

So far, a small portion of the wall has been deconstructed in order to assess its role in the flooding. Meanwhile, the Border Patrol is

investigating the impact illicit tunnelers may, or may not, have had on the dynamics of the water flow in the wash, and to what degree dilapidation in the structures themselves over the years may have been a factor. In my reading I’ve learned that there have been numerous different repairs made to the Wash in the last few years that will be examined as well, which will no doubt take weeks if not months to sort all this out. But, it will of course be very curious to see how they treat the tunnels afterwards, who will actually take responsibility, and if the migrants and smugglers themselves won’t end up receiving the blame. At this point, I am anxious to see how the Border Patrol will own up to their portion, if indeed their little wall was responsible, and just to what extent that simple barrier might have caused damage.

[Image: Mexico ties flooding in Nogales to U.S. Border Patrol-built wall, 2008.]

[Image: Mexico ties flooding in Nogales to U.S. Border Patrol-built wall, 2008.]I guess I just find it totally bizarre, symbolic, and possibly a foreshadowing scenario as borders, security, hydrology, and migration have, literally and metaphorically, fallen into the same state of disaster together here. If migration is liquid, and border walls show that they will only force the flows of migration underground, then there is something very telling in this picture – maybe that the floods of migration can’t be stopped by a mere wall, in fact a wall may only be that which causes them. Shame, it seems like a tragic lesson to learn. Here, any competent treatment of these issues have crumbled under the weight of a single five foot high border wall that was erected deep underground, out of public and official view, mind you, beneath appropriate legal process, and totally ignorant of the larger environmental impact. If this miniature border fence can resound with this much disastrous effect, then imagine the impact of a 700 mile long stretch of border fencing.

[Image: Mexico ties flooding in Nogales to U.S. Border Patrol-built wall, 2008.]

[Image: Mexico ties flooding in Nogales to U.S. Border Patrol-built wall, 2008.]Yet, the murky border-as-hydrologic-migration-security-disaster calamity doesn’t end there.

One state over in Texas, the DHS is in the process of constructing a portion of the border fence directly on top of these old decrepit levees in Cameron and Hidalgo County that have long been considered inadequate along the Rio Grande River. In a

New York Times piece two decades old now, we read, “The Rio Grande forms the longest section of the border between the two countries. But what happens to that border when the river itself changes course?” The Rio Grande, as the reporter put it, is literally a

liquid border, modifying territory constantly between both sides. “To try to prevent the Rio Grande from changing course and causing more border disputes, the Mexican and American Governments have spent millions on course corrections and flood-control programs, including the construction of canals, dams and levees.” Not to mention a host of treaties, and other collaborations of militarization and border patrol which have certainly helped redefine the border in other mysterious ways, too. There is perhaps even greater liquidity to these other non-geographic aspects of boundary definition.

More interesting, however, the article tells us about a tiny island --

Los Indios Banco No. 156 -- “created by a shift in the river's course” from a 1967 hurricane and was purchased by retired USAF Colonel Herbert Williams, who then claimed ownership of it and declared its independence.” This, if I understand the history correctly, became the Cherokee Nation of Texas Reservation. Actually, it's a pretty fascinating story about how Colonel Williams was eventually appointed as the Sovereign Head Chief and Trustee, and how he gave safe haven to the Neches Tribe of the Cherokee People of Texas, but I really don’t know much of the detail. As far as I know, the island today is filing petition to become a federally recognized reservation.

Also mentioned is the “sleepy village of Rio Rico” which “occupies territory that used to be part of Texas. But for the last 15 years, the town and the land have belonged to Mexico, even though most of the fewer than 1,000 residents who were born here claim American citizenship.” It crazy to think, that, for instance, having been born in the U.S., and lived there for fifty years, you could at some point come to discover that you’re living in Mexico now without ever having left your hometown. Suddenly, you don’t owe property taxes anymore, but your new riverfront properly is worth 10 times less, and you are now considered a citizen outside your own country, an ex-pat just for staying put all those years.

Or, what about the reverse prospect: instead of facing years in jail trying to cross the border illegally over and over again, migrant communities from Mexico set up camps on the banks of the Rio Grande River, patiently living a simple life on the water, receding and moving forward again sticking close to the dredged banks, waiting for that day their grandchildren realize the river’s course had completed its shift and they are now technically camping on U.S. soil, having migrated neither legally nor illegally, but quite simply with the course of nature, their future sons and daughters will now finally be entitled to an American citizenship, should they want it.

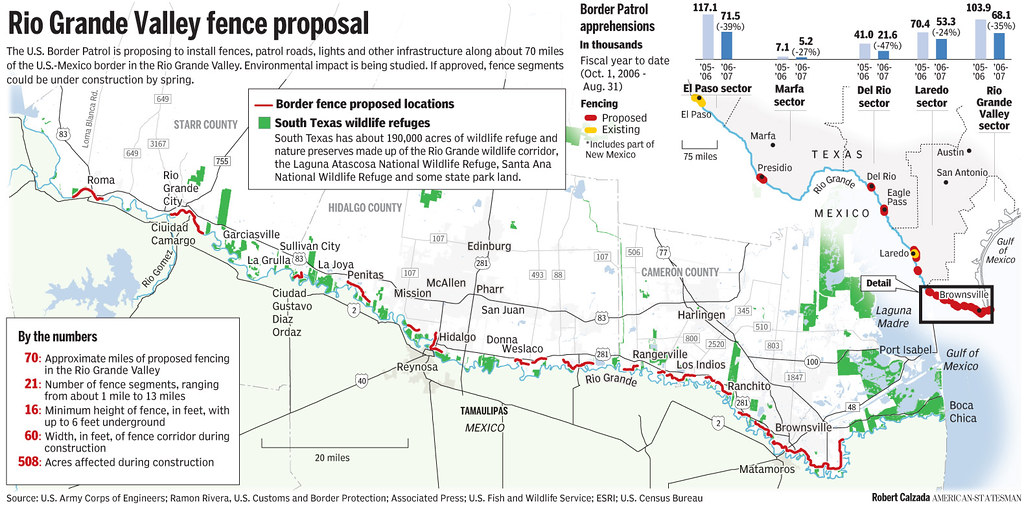

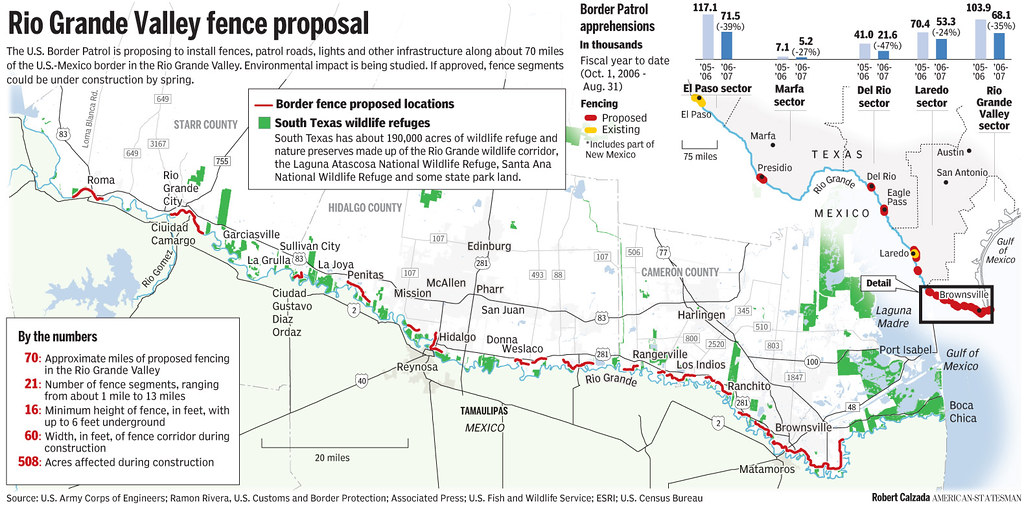

But, that probably won’t happen, because the levee repair and fence construction is part of a larger strategy to build 70 miles of fencing in the Rio Grande Valley in twenty-one separate parts. According to

this article, commenting on the DHS’s plan for the area after they updated their environmental impact statement:

“the fence will affect 21 wildlife management areas and refuges in the Rio Grande Valley. Short- and long-term negligible to moderate adverse impacts on wildlife and aquatic resources will be expected.

To minimize that impact, small openings will be integrated into the semi-transparent steel fence to let animals pass through. A biological monitor will be on site during construction to account for occurrences of special status species, including ocelots and jaguarundis.

Approximately 376 acres of vegetation will be cleared before the fence is erected.

The barrier, which will be built in segments ranging from one to 13 miles in length, will be able to withstand a 10,000-pound vehicle crashing into it at 40 miles an hour, the report states. And it will be "aesthetically pleasing to the extent possible."

With regards to the levees in Hidalgo County, they have been considered the weakest in the entire area for a long time.

“the system is designed to handle the rain that accompanied deadly Hurricane Beulah in 1967, but that there are portions of the levee that could overtop with storms of a lesser magnitude.

Portions of the levees in Hidalgo County are between 3 to 9 feet below the height they should be, according to IBWC.” (source)

In fact, according to the

same article, the potential for flooding a couple of weeks ago was so great “that the Red Cross wouldn't set up shelters in the Rio Grande Valley until after the hurricane had passed.”

K. Rod Summy voiced some cogent points as well, asking:

“Have any hydrological studies been conducted to assess the potential impact of proposed Border Fence on the stability of the flood-control levee systems in both southern Texas and northeastern Mexico, and what is the probable impact on the Rio Grande Valley region if the levee systems in either Texas or Mexico should fail? If hydrological studies have indeed been conducted, who were the researchers, what are their credentials, and what was the type and quality of the data used to reach the conclusions reported in the EIS? If any legitimate hydrological studies relating to this topic actually exist, their methodologies, data and results should be discussed in open forum so that the people who live here can judge for themselves whether or not conclusions reported in the EIS are valid.”

There’s been tons of debate in past years about whether a fence belongs there or not, whether to build a fence or just new levees, to combine the two, or just let the Rio Grande do its own thing and act as a natural barrier against migration. Regardless, the levees are in desperate need of repair, and after what we witnessed with hurricane Katrina it is next to impossible to accept they have not yet been replaced in recent years.

[Image: Via the excellent No Border Wall blog.]

[Image: Via the excellent No Border Wall blog.]Through some very critical resistance to the border fence from community members in South Texas led by the

Texas Border Coalition, a group of officials and business leaders representing multiple cities and counties, a compromise was eventually struck.

“That plan significantly cut back the amount of private land that would have to be used for the project in Hidalgo County by building a concrete wall into the riverside of the existing levees. That way the county would get its needed flood protection and Homeland Security would meet Congress' mandate to build a barrier along 670 miles of the U.S.-Mexico border.

San Benito, Texas-based Ballenger Construction Co. won the $21.4 million contract to build the 1.76-mile Granjeno segment. Pasadena, Texas-based SER Construction Partners won the $12 million contract for the Donna segment, which is just under a mile long.” (source)

But something about it doesn’t sound quite as genuine as that. After having already destroyed one levee in order to build an 18-foot concrete wall, Chad Foster, the mayor of Eagle Pass, Texas, speaking on behalf of the coalition, was quoted as saying something to the effect:

"This only makes sense if you work for the Department of Homeland Security, the same government agency that failed the people of Mississippi and Louisiana during Hurricane Katrina," … "They designed a wall that will cost American taxpayers $16 million per mile to build in some sections - $50 billion over the years.” […]

“Mr. Foster said Homeland Security saw the requirements for levee repair as a way to achieve its goal of building a fence along the border, adding that "the only places where they are paying to rebuild the levees are in areas where Border Patrol identified a need for a wall.” […]

"The government is paying to repair the levees in bits and pieces," he said. […] In Texas, some of the new border fence is being built more than a mile from the border, where Mr. Foster said it traps workers, families, farmers, ranchers, retirees and wildlife on the Mexican side. He said the new fence will cede thousands of acres of U.S. land to Mexico.” […]

"Emergency or law enforcement personnel won't be able to rescue people or property when fire, flood or crime requires help," Mr. Foster said. "Wildlife won't be able to access the life-giving resources of the Rio Grande River. People and wildlife - in many cases, endangered species - will die. Congress and President Bush should grant them relief and stop building an absurd border wall that endangers lives." (source)

Sounds like Foster hit it on the head when he described the DHS’s intention as less about a sincere effort to repair the levees independently (since they’re in need of it), but using them as both a bargaining chip to force local resistance to cave in to pressure and sign on to the construction of a fence, and maybe as a way of incorporating and disguising it as a public works project, perhaps allowing it to bypass further legal and/or environmental review and approval. I mean, what is this thing technically classified as, a defense project, or civic infrastructure, or some new undetermined classification of barrier? How might that determine then how these levee/fences are maintained, or governed in the future, about the decisions that can be made to alter them, and what in their surrounding area may be acquired later on for their benefit, what will be the land use cost of combining these structures?

I don’t know, I’m just skeptical of such a merger. I need to do a lot more research on how the post 9/11 security landscape has technically and radically revised and militarized different forms of planning in this country, from building code and regulations around urban design to federal environmental policy and even congressional approval processes; specifically, the political and extralegal mechanisms that are being practiced to encode security architectures into the domestic fabric with minimal resistance, and what powers the president and the DHS have been unilaterally afforded to do so. Another area in all of this I am admittedly very poorly versed in. But, curious, how compromises like a levee repair/border fence project will affect the future rules and regulations around other public works undertakings, how they are packaged and will be controlled.

Also, from another interpretation, it looks like the levees are getting some absurd protection in the form of a border fence – as if the fence were installed on top of the levees to explicitly guard them from sabotage – which is ridiculous, but speaks to the larger short sightedness of a border fence in general, I think; as if such a barrier were the answer to all of Chertoff’s prayers, when in reality it’s really just for show, or, as Bruce Schnier calls it, the production of “security theater” to merely allude to control.

Adding to the unimaginability (and lack of imagination) in all of this is the fact that

they’re doing this construction now during high hurricane season, which obviously only endangers the locals more with no levees at all in the interim. What if construction for some unforeseen reason were forced to halt, or was derailed by something along the way? Seems not only incredibly unwise to try and tackle this now, but blatantly reckless. But, isn’t this the kind of response we have come to expect already?

[Image: Construction of the Granjeno portion of the border fence in Texas. (source)]

[Image: Construction of the Granjeno portion of the border fence in Texas. (source)]A 1.76-mile wall is currently under construction in Granjeno. You can read about it

here. Harlingen-based Ballenger Construction Co. got the contract to erect this first portion in Hidalgo County. “At another segment, about eight miles east of the Santa Ana National Wildlife Refuge, at least one crane had started peeling away grass from the side of the levee. Pasadena-based SER Construction Partners Ltd. won the contract for the 0.9-mile segment.”

But, given the DHS’s poor levee repair track record, and that the levees are probably only really being restored to where they should have already been by now, one might, in a bit of silliness here, imagine a new wave of migrating border wall surfers just floating over the top of it one day, like storm chaser coyotes, armed with durable rafts, body boards and a bunch of sex wax, ready to just ride the floodwaters over the border. Like surfers wading on the horizon for the next set of waves to floor them towards the shore, migrants will wait by the wall in the same anticipation of rising floodwaters, courageously eager to be lifted over the wire while perhaps venturing into a new realm of disaster sport. At that point, you really could call them, waves of border crossers.

I mean, does anyone beside the DHS believe these Rio Grande projects are going to prevent migration? Does anyone other than the DHS think that a combined levee/fence will actually protect the local communities there from floodwater? From what I can tell, local communities aren’t very confident, and in the end they might see floods of both water and migrants washing through their neighborhoods. Sadly to say, perhaps only time will tell.

The DHS has divided 22 miles of Hidalgo County’s border wall into seven different segments along levees throughout the county. However, not all of the border fencing/levee repair will look like what I’ve described already.

Roma, Rio Grande City, and Los Ebanos in Texas, as well parts of Arizona’s San Pedro River, may be lucky enough to host a different type of fence, one that will allegedly be movable, in the event of a hurricane, designed to try and help mitigate the impact to the floodplain.

“This

"movable" fence proposed by the Department of Homeland Security would be concrete jersey barriers topped with about 15 feet of tightly woven steel fencing. The International Boundary and Water Commission is reviewing the proposal to make sure the fence does not violate treaties with Mexico and could be moved away from the river before it floods.”

[Image: A U.S. Border Patrol vehicle drives along the top of a levee near the International Bridge. The U.S. Department of Homeland Security has released a report on the impact the border fence will have on the Rio Grande Valley’s environment. Via, The Monitor. ]

[Image: A U.S. Border Patrol vehicle drives along the top of a levee near the International Bridge. The U.S. Department of Homeland Security has released a report on the impact the border fence will have on the Rio Grande Valley’s environment. Via, The Monitor. ]My understanding is that this fencing

has not yet been approved because it still needs to be shown that the fence parts are capable of being moved swiftly enough in time to have a reliable impact on preventing flooding. Just exactly how they would move, or be moved, seems vague and unclear to me. But, what a huge task that would seem to entail, consistently nonetheless, despite the fact that such a plan probably makes no sense at all.

“Foster says the idea that officials are even considering such a thing belies one of the real problems with the whole idea of fencing. To avoid constriction in the 100 year flood plain, which would violate a 1971 border treaty between the U.S. and Mexico, any fencing in the Rio Grande Valley would have to be built as far as a mile inland, leaving tens of thousands of Texans on the 'Mexican side' of the fence, and not only require that they pass through border checkpoints to get to the grocery store and the doctor, but requires ambulances and other emergency vehicles to pass through Border Patrol checkpoints to get to them.”

Melissa del Bosque hammered on the financial burden of such a plan,

writing, “Since the Congressional Research Office estimated $49 billion for 700 miles of border fence, then it’s reasonable to expect that movable fencing will cost taxpayers even more. Plus, the government will need to pay someone to move the fencing when disaster looms. Sounds like whoever gets the contract will also deserve hazard pay — add that to the nation’s already-bloated border security costs. […] Can’t wait to see which private company gets the fat contract to move the fence before major flooding events.”

Well, now that Blackwater has announced they are scaling back their security services portfolio, I’m sure they already have a bid put in for the potential job.

[Images: Arizona city seeks moat to secure Mexico border (Reuters, Guardian).]

[Images: Arizona city seeks moat to secure Mexico border (Reuters, Guardian).]However, none of this even begins to get at other wild proposals like the

Weir Project that would essentially aim to widen parts of the Rio Grande

through a series of low dams or weirs across the desert flood plain river in order to make the stretch large enough to discourage border crossers over water; or the 10 feet deep by 60 feet wide

manmade moat (or a

"security channel") that government officials have discussed to build by flooding large areas around Yuma in South-Western Arizona, which would theoretically revive a derelict two-mile stretch of the Colorado river; or the issues yet of

evacuating detained immigrants from detention facilities that lie in, or close to, the floodplains and other endangered areas along the border vulnerable to storms and hurricanes; or

how border checks will be handled during the event of a storm; or the water jug wars between humanitarian relief organization

Humane Borders,

park officials, and

mysterious bandits. It all seems to stem from the fact the DHS puts the human impact of their strategy completely secondary to the symbolic stature of just getting the damned border fence completed, and the fallacy that everything can be solved in one fell swoop, with one fell structure like a flexible fence of some kind, or a dynamic flood wall, when in the end it is doubtful any of the issues will be properly resolved at all – perhaps only intensified. It’s as if the pentagon imagines a nature that can be easily conformed to fit the security wet dream itself. Sure, Chertoff can claim he is devising a border security strategy that is sensitive to, and works in accordance with, the environment, but it’s the same old game of smoke and mirrors. In the end, the environment pays.

[Image: People lined up at a shelter in the city of Matamoros in Tamaulipas State. More than 4,000 people, mostly from low-lying regions along the river and the coast, crowded into schools for shelter. NYT. ]

[Image: People lined up at a shelter in the city of Matamoros in Tamaulipas State. More than 4,000 people, mostly from low-lying regions along the river and the coast, crowded into schools for shelter. NYT. ]I mean, movable walls that would somehow part in time for floods hailing from the sky, who does Chertoff think he is, Moses?; levees meant to stop migrants; border fences used to stop floods; little holes punctured in the fences meant to help the wildlife when the larger structure itself probably has more to do with killing it. Over thirty environmental protection laws waived to make way for construction of the border fence, private land seizures,

agricultural drains,

government intimidations, forced buyouts, American communities and schools forfeited to the Mexican side of the border … the list goes on, believe me. It looks like one colossally confused barrier to me that may neither be a fence or a levee, but just another monument to the failures of the exceptional idiocracy ruling over this country that would rather preserve the ideology of a border fence than the actual precious resource of the border ecology itself.

Anyway, this ridiculously long post has rambled on enough, I am sure I've drowned plenty along the way, and nearly given myself sea sickness going over it a few times. So it must be leveed right here and now, at least for the short time they'll hold. Adios.