Akin to something crossed between the grassroots filmmaking of

Kids with Cameras and the participatory-culture of the

Border Film Project,

MAQUILAPOLIS, or “City of Factories”, is a self-produced documentary made by (and about) the female workers in Tijuana's sprawling maquiladora assembly factories.

Shot on digital cameras distributed to a group of promotoras (community-based activists) after a six-week technical training and story-telling workshop, the film follows and “meets women who are each dealing with the hardships of environmental toxins, labor rights abuse, infrastructure and housing issues”, and, among other things - women's rights.

Filmmaker

Vicky Funari, and artist

Sergio De La Torre, collaborated together with the women's organization

Grupo Factor X in Tijuana, to organize and help the workers adapt the camera to their daily lives. Through a series of intimate narratives and teamwork, the documentary assembles a portrait of a community managing to create “liveable solutions to the complexities of life in a globalized city“.

Sergio is a friend of a

good friend of mine (both of whom are doing great work), but I have to say, this looks like a fascinating project - and I can't wait to see it. The film “approaches the workers as experts who can provide us with keys to our common future”

the website reads, “inviting them to co-author their own story on videotape.” And, isn’t that what it's all about: communities coming together to bring their own stories to the forefront of larger debates, empowered by grassroots artistic collaboration?

Though I haven't seen it yet, I will venture to say, what sounds most promising about Maquilapolis besides any poignancy of what it reveals about the maquiladoras themselves (or the real-life cultural impact of “globalization” on the Mexican side of the border), isn’t just the cinematic experience the film leaves behind, but, rather, what it has already gone on to establish with this community of workers for the future. The women continue to use the cameras today as a sort of fixed apparatus for recording and relaying the ongoing struggles and visions of their daily lives, symbolically empowered by their use of the very consumer products they assemble in the factories. The filmmakers are actually looking for

additional funding to host an editing workshop in hopes of encouraging more people to become active in the day-to-day documentary story-telling of their plight playing out along the border.

[Image:

Tribeca Review of

Maquilapolis, 04.13.06.]

With all the vitriolic attention on immigration spit out in the media these days, distorted by gross exaggerations of the border being the number one threat to U.S. national security, the time for a genuine depiction of US/Mexico border geopolitics -- made (and told) by the people central to the confluence of hardships there -- is crucial to our understanding of why, and how, we should seriously consider addressing the region.

In short, the hype over how the maquialdoras were going to boost the Mexican economy has hardly panned out, nor has this industry at all helped to alleviate the pressure of illegal immigration to the United States. In the last 20 years the US/Mexico border has been the fastest growing population of any border region anywhere in the world. There are 12 million illegal immigrants estimated living through out the U.S., but the numbers also suggest approximately 12 million people have migrated to the southern border in that same time, driven by an explosion in consumer goods manufacturing and import/export markets, which have made the 2000 mile stretch the most densely populated geography between any neighboring First and Third world nations. An additional 10-15 million are predicted to crash the border zone by

2020.

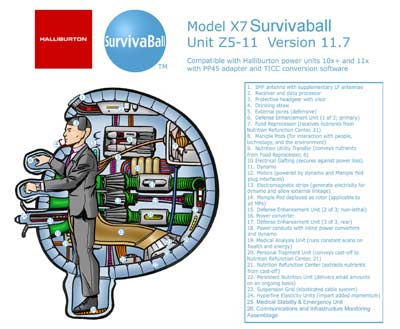

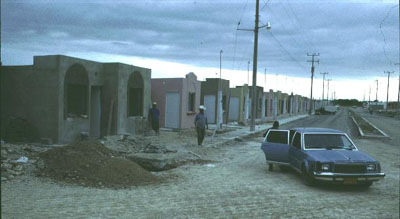

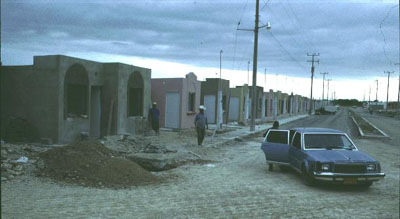

[Image:

Bridging Troubled Waters in Ambos Nogalesby Miriam Davidson, 1998.]

According to Tyche Hendricks in the

SF Chron, “The largest concentration of maquiladora jobs is in Ciudad Juárez, across the border from El Paso, Texas, followed by Tijuana, just south of San Diego. Reynosa, across the Rio Grande from McAllen, Texas, is third in maquiladora employment.” He goes on to write that Reynosa employs “more than 92,000 workers in 200 factories [that] produce everything for the U.S. market from distributor caps to candy canes. Those jobs have made border cities into magnets for workers from the interior of Mexico, where government support for subsistence agriculture has evaporated. The largely American-owned factories, which first arose in 1965, now employ nearly 1.2 million people.” There are approximately 3,500 plus maquiladoras currently operating along the border today.

The failure of the maquiladoras is largely in part because they are essentially legitimized slave factories as opposed to any kind of viable economic alternative for Mexico's grossly lopsided economy. From what I've heard, the average wage of a worker is around $95 a week, and that's working overtime. Further, neither country’s labor policy has served in any way to discourage exploitation on either side of the fence, but rather has had the opposite effect. “These massive cross-border flows occur by design” says

Douglas S. Massey, “under the auspices of the North American Free Trade Agreement. But at the heart of NAFTA lies a contradiction: Even as the United States moves to promote free movement of goods, services, capital and information, we as a nation somehow seek to prevent the movement of labor. We wish to create a North American economy that integrates all markets except one: that for labor“.

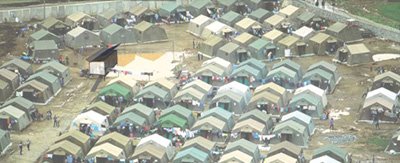

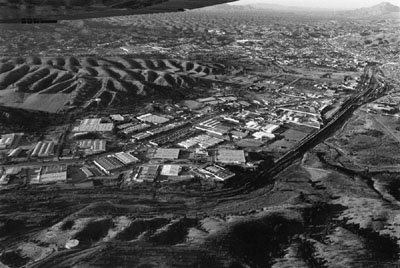

[Image:

Maquiladoras, by Ingolf Vogeler.]

Those concerns have also been compounded by transnational companies shopping around the globe for competitive exploitable labor, and recent moves have taken many of the jobs to labor markets in Asia. This

article reported that roughly 226,000 workers, in a relative short period of time between 2000-01, were laid off by these foreign companies as massive shifts of maquiladora portfolios left Mexico. The author says, “And where do you think all those people went?”

To further show that the maquiladoras have not helped to reduce the influx of illegal immigration, Hendricks

cites a U.S. report showing that the number of people working in these factories along the border still continues to rise, as do the number of factories themselves. From '90 to '05 Maquiladora jobs in Mexico have increased from 454,432 to 1,174,234. So, it is not entirely unobvious to assume that the constant increase in the number of factories crowding the border and the people they employ are in some part responsible, if even perhaps indirectly, to the surge in the number of border-crossers.

Massey, a professor of sociology and public affairs at Princeton University and co-author of the book

"Beyond Smoke and Mirrors: Mexican Immigration in an Age of Economic Integration," has

stated, “Instead of viewing Mexican migration as a pathological product of rampant poverty and rapid population growth, we should see it for what it is: a natural byproduct of economic development in a relatively wealthy country undergoing a rapid transition to low fertility in close association with the United States.”

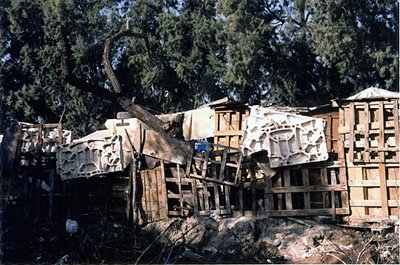

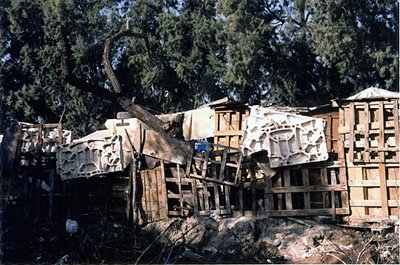

[Image:

Many of the homes in Chilpancingo are made out of packing crates the workers buy from the maquilas,

2002.]

To make matters even worse, while the debate remains polarized between a conservative agenda seeking to convert the issue of immigration into one of national security (in order to contract billions of dollars into militarizing the border), and the left, who at least emphasizes the issue as a complex permutation of our own labor policy and practice - the other great concern (which seems to get less and less attention) is the swelling environmental crisis that consumes the region in nightmarish swaths of habitat degradation and catastrophic waste-disposal.

As most of us know, environmental justice is generally linked to economic and social justice. So, it can be the least bit surprising to attempt an explanation of the overwhelming poverty that has piled up along the border and the issue of mass illegal immigration in terms of the environmental consequences systemic to the institution of exploited labor that has defined the border.

[Image:

Community members built this makeshift bridge across the river of run-off that divides the two sides of Chilpancingo,

2002.]

The state of roads and sewage infrastructure in most border cities “is sliding toward desperate," says UC Berkeley Professor

Harley Shaiken, an expert in labor and trade. "The maquilas are paying minimal if any taxes, and the result is an infrastructure that is inadequate to the growth taking place."

According to a friend of mine, Chris Nelson, who is focussing on environmental policy enacted around the border, “Approximately 11% of all the trash in Texas's Rio Grande Valley landfills in 2002 came from maquiladoras.” Meanwhile, Tijuana is an environmental disaster. Nelson proposes an overall strategy of cleaning up the border as a way to begin restructuring the transborder economy of the region through mutual civic projects that incentivize environmental responsibility, and by bringing forth comprehensive and progressive socio-economic transformation programs through "operationalizing industrial ecology".

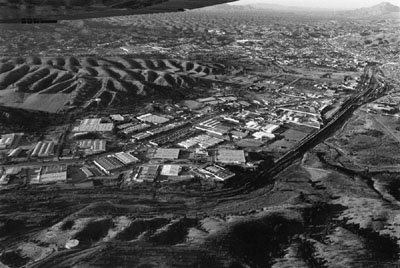

[Image:

Ecoparque, an experimental water filration/irrigation

project on the

steep hillsides of Tijuana.]

Anyway, more on that later. In the meantime, if you get a chance to go see the documentary – do it.

Here’s the schedule of dates. And, if you have any spare cash, don’t be afraid to

donate. And, if you do manage to see this, shoot me an email, or comment here, because I’d love to hear responses to this. If I get chance to see it, I’ll post a review here. Stay tuned.