An About Page (For Now)

[Image: Transfer, that seems to longer exist, once had a great collection of photos in The Anti-Sit archive.]

[For a long time now people have been asking me why I don’t have an About Page, and told me that Subtopia could really use one. I guess I’ve been resistant to such obligatory blog clichés. So, three years after takeoff here is a little essay I read at Postopolis! in LA that may as well suffice for my About Page, at least for now. Though, I still don’t want to make it official, I don’t know why – I guess I just like the idea of the blog defining itself through out the course of its life rather than the being beholden to a big declarative statement that sets a stage, or its parameters. We don't like borders like that. Subtopia is about a process of unfolding – not a thing, per se. Either way, people have also encouraged me to post this after hearing it at Postopolis! so at their behest I’m doing so.]

What is Subtopia?

Well, to start, you could say it is the seamy underbelly of the architectural blogosphere, where remarks on the sexy curves of design are quickly supplanted by long hard stares at the cold rigid boxes of global detention – but, before I try to answer that question more precisely let me first answer the question: what led to Subtopia?

Several years ago I was working with the Homeless Coalition in San Francisco bringing together groups of architects, activists, homeless community members, and non-profit developers to think about different ways the city might consider new housing options, from ad hoc shelters to supportive housing design.

Growing up, I had great interest in architecture – my family was convinced I’d go on to become an architect – but, by the time I parked my confused and penniless ass in college I determined my interest was less in designing buildings than in looking at architecture as a means to reflect on politics and social issues -- as they are subjects of space.

I was certainly curious what design could do to engage social justice, but I often found myself paying more attention to the de facto landscapes of San Francisco and how the homeless were generally affected by living in the streets. The more closely I observed the city from the perspective of the homeless I soon began to realize, despite the reputation San Francisco had for being super homeless-friendly (which to some extent is true) there was really a more subtle underlying anti-homeless landscape taking shape.

[Image: Transfer, that seems to longer exist, once had a great collection of photos in The Anti-Sit archive.]

So, while Mayor Willie Brown and later Gavin Newsom would attend press conferences for the opening of a rehabilitated shelter project, city contractors would be busy bolting in decorative barbs and insidious little bench fortifications that were very obviously meant to prevent the homeless from taking any temporary refuge resting on building ledges, sidewalks, or from sleeping in business doorways. Soon, I learned the city had timed the sprinklers in the parks so the grounds would be too wet for homeless people to camp out overnight. Street cleaners would take massive hoses of bleach to sidewalks before the crack of dawn to uproot the regular encampments that gathered around abandoned buildings in the Tenderloin. New gates were installed to seal off alleyways downtown, blinding floodlights hit innocuous spaces under the freeway, homeless carts were carted off moments after they were discovered stashed in parking garages – it all seemed like a petty act of cruelty to me.

Beyond these visual measures, new ordinances were passed that made panhandling illegal in those parts of the city I’d seen the same homeless people collecting change for years. This was soon followed by a new anti-loitering policy that seemed selectively targeted at homeless groups who gathered every day in certain neighborhoods that were as much theirs as anyone else’s. Then, an anti-littering ordinance hit the streets and as far as I could tell was really only enforced on homeless people. By Christmas, the mayor was even so kind as to offer one-way tickets for homeless people to go visit their families out of the state. One way tickets.

In short, San Francisco was being quietly transformed by an egregious homeless criminalization agenda, from minimalist public space fortifications to a strategy of policy enactments aimed with the overall effect of permanently uprooting the homeless from any visible spectrum in the streets.

[Image: Taken from a photo collage by Bret C. Wieseler, for his project (In)Security: Access and Anxiety in the Wall Street Financial District.]

This marked my first realization of how landscape could be devised into a kind of weapon, targeted at a specific group of people with the sole aim of removing the informal infrastructure of their survival and thereby forcing them out of the city. It was a kind of domestic urbicide, and all the city’s rhetoric about being a progressive sanctuary for the homeless just seemed like total farce at that point.

Now, I was raised by a father whose entire life was devoted to public service. Not only was he one of the youngest ever city managers in California, but later ran just about every major transit authority in the country – he helped design BART and basically brought light rail public transpo here to the U.S.

He’s no longer here but if he instilled any philosophy in me it was that cities and public space are what largely constitutes our sense of a collective identity, they are what brings communities together -- what allows plurality, ethnic diversity, and multitude to flourish. His attitude was that our greatest civic ideals are only as good as we can realize them in our social and public spaces, and that cities should be the great modern legacy of humanity.

Then -- 9/11 hit. And soon this country went into its disastrous tailspin before undergoing perhaps the greatest landscape transformation I’ve witnessed so far in my lifetime. The anti-homeless landscapes of San Francisco, New York City and LA soon spread to cities across America, but seemingly injected with some crazy urban steroids now. Surveillance cameras became a new norm. Classic public spaces downtown were now restricted and cut off by small private armies of security guards. Bollards and barriers of all shapes and sizes crept up everywhere, tree planters dominated the sidewalks, activists were now given specific designated zones whereby they could carry out their protests; we got color-coded national threat level meters, checkpoints to enter our children’s schools, detention spaces built into sporting event venues – the city suddenly zipped itself up inside a new kind of fortress armor and posed as if it were ready for war.

[Image: Via Google search, photographer unknown.]

The only problem was, there were no insurgents, not really, not unless you counted those pesky homeless elderlies dragging their lives through the streets who soon found themselves the guinea pigs for America’s new urban front for the “War On Terror” here in the good ol’e homeland.

It was at this point my interest in militarism and the political dimensions of space and architecture began to come together. So, Subtopia was soon launched – at first as a kind of dumping grounds for research I was pulling together around the militarization of space, but later it took on a kind of life of its own – much like blogs often do, I suppose.

So, finally, what the hell is this Subtopia thing anyway?

In its broadest sense, it’s about: Architecture (or more generally) ‘space’ as it is designed or used as a tool for social control. It is where urban and military planning formally and informally collude. It is what manifests in something as specific as a particular war doctrine, a bunker design, or the strategy for surgically bombing a city but can also be as pervasive as an entire culture where militarism regularly intrudes in our daily lives through much less visible means: Army recruiters using MySpace, f.e., video game imaginaries of the Arab world; web based border surveillance portals that turn bored living room patriots into internet vigilantes.

Subtopia is my attempt at chronicling this spectrum of physical and virtual space that corresponds with war and political violence as it translates in landscape.

Now, ‘Military urbanism’ is hardly my own original topic. I’m just picking up on the trails of brilliant work started years ago by the likes of Eyal Wiezman, Mike Davis, Stephen Graham, Lebbeus Woods, Foucault, Virilio, to name just a few, all of whom have articulated (much better than I ever could) the many ways and forms that space functions as a medium for conflict; and how landscape can be harnessed, or even designed to most effectively manage the scales and reach of military control.

Now, while I’m not an architect, the way I see it: Architecture’s definition (in rudimentary terms) can be boiled down to either providing a basic form of shelter, or organizing a corresponding set or system of walls that either blocks or enables human mobility in some fashion. Since mobility and the right to movement are inherently political (perhaps even the most crucial of human liberties) the concept of a border fence is as much about architecture as the design of a public square. For that matter, so is the detention center, the underground smuggler tunnel, or the prison ship.

[Image: Immigration Detention Tent City, in Raymondville, TX, via E. Elizabeth Garcia.]

My initial questions were: What role should (or should not) architects have in this context? How is conflict space inherently expanding the boundaries of what can be considered architecture? What are the ethical questions we should be concerned with when observing the production of space as it specifically relates to national security, global migration, torture, activism, and so forth?

Because architecture is inherently territorial this way, I’m interested in design less for design’s own sake but more in so far as it connotes a politics of space; that is to say, as it prescribes a law, or enforces a behavioral code, facilitates a human or civil right, or -- puts a limit on the exercise of those rights, and as it may deprive access to basic human liberties.

However, as I said, since I’m not a designer my interest is more in looking at how space can be invariably hijacked, or reused for a specific political agenda, how it can be subject to exploit in order to serve power, as well as how space can lead to power’s own subversion.

Since architecture has always historically been a part of the vocabulary of royal power, and while perhaps today that translates to architectural theory being deployed to justify some of the most controversial military interventions (like the Israeli Security barrier f.e. as well as other modes of urban warfare), not only am I curious how this legacy continues to develop through time but am more interested in the spatial backlash to military urbanism; the spaces that are emerging in the cracks – Gaza’s border tunnels f.e. – spaces of asymmetric conflict; a counter-empire landscape, if you will.

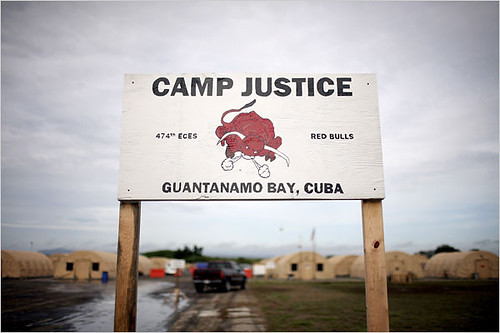

[Image: Portable Halls of Justice Are Rising in Guantánamo, photo by Todd Heisler/The New York Times.]

What’s most interesting about space from a Subtopian point of view is that no matter how hard ‘power’ pushes through it new spaces always open up and emerge in response; which creates a kind of interminable balloon effect in the constant shifting tug-of-war imbalance of military power’s spatial dimensions. And so I wonder about this notion: can state power sustain itself by completely dictating the terms of the landscape alone?

Now, I certainly don’t pretend to have any answers. Subtopia, so far, is really more so about creating my own space of interrogation, to ask questions and investigate this sort of classic interrelationship between people and space: I mean, there’s Us as ‘people who create spaces’ and then there’s ‘those same spaces which in turn recreates Us as a people.’ It is this ongoing mutual reconstitution of space and humanity which fascinates me much in the same way our political process is both ‘shaped by Us’ as well as being ‘shaping of Us.’

Anyway, I like to think of myself as serving a crazy little blogger’s role on a larger forensics team of urban investigators and human rights advocates, scrutinizing spaces of conflict to see what they might be able to tell us about the power structures behind them and the ethical standards practiced by our political institution. If there is a spatial logic to the War on Terror, what can we gauge from that and how can it help shed light on the political rationale of our government’s actions?

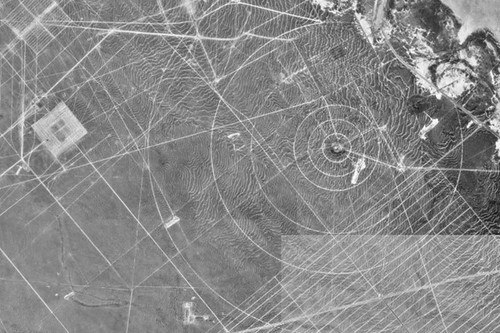

[Image: Dugway Proving Grounds, Utah. Satellite image via Polar Inertia.]

This is what drives my chief interest with Subtopia: trying, from my measly vantage in front of my laptop, to discern these types of spatial politics: how politics program spaces, and how those spaces can be used to reshape the political landscape. So, I’m using the blog as a way to try and catalogue this stuff to see what spaces like immigration detention facilities, secret CIA torture jets, border fences, floating prisons, can possibly tell us about the social foundations of our democracy, about the ideals that democracy professes to protect.

To me, what is claimed to be a “War on Terror”, or a “War on Drugs” appears more likely a War on Law, or, a War on Space itself. And I guess, like my father, I see nothing more pressing (especially today) than preserving our rights to publicly control the making of space and the political transparency of our own cities.

6 Comments:

I like this page and have for a long time. Interesting and intelligent and comprehensive.

At the same time I'm glad you're not in charge of polices having to do with homlessness, national security, immigration, or border control.

And whay is that, Gerard?

Image #3 is cropped from a photo collage by Bret C. Wieseler, for his project (In)Security: Access and Anxiety in the Wall Street Financial District.

http://asla.org/awards/2007/studentawards/393.html

sweet! thanks AT.

I found your blog at about 4am this morning and all I can say is "fascinating." All your posts on border tunnels are extremely helpful. I'm a YA novelist working on a story featuring those tunnels as a target for the worst kind of anti-immigrant hate crime. Seems I can't help imbuing my stories with serious political awareness between the lines of teen humor, adventure, angst, and romance. Your premise--politics as manifest through space and architecture and manipulation of the environment--struck a chord. Reminds me of the juvenile corrections center up the street from me a few miles--the sign in front, outside the razor wire fence, declares it to be the "Freedom Center." War is peace.

well bryan, believe it or not i have been browsing your blog : ) i found your about page to be quite cool and a well written and very informative read. esp. given my ignorance of the topic. i hope all is well. talk to you soon.

Post a Comment

<< Home