Great Walls of Fire

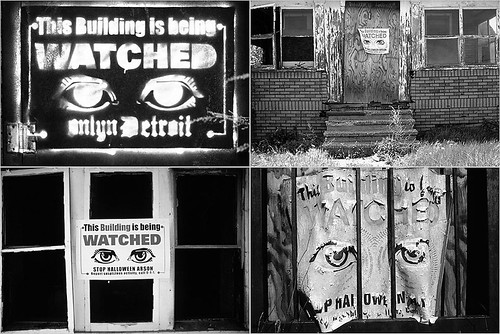

[Image: Neighborhood Watch, Detroit. Photo by Camilo José Vergara, NYT.]

Camilo José Vergara, author of American Ruins

Sadly, I didn’t even know about Devil’s Night until now. Citing wikipedia here, Devil’s Night, for those who don’t know:

… is a long-standing tradition predating World War II, with anecdotal incidents occurring as early as the 1930s. Traditionally, youths in Detroit engaged in a night of criminal behavior, which usually consisted of acts of vandalism (such as throwing eggs at the homes of neighbors, scribbling on windows with bar soap, or stringing toilet paper in trees). These were almost exclusively petty vandalism acts, causing little to no property damage other than perhaps a damaged mailbox or eggs hardening on windows. These acts still go on today.

However, in the early 1970s a dark side of this holiday emerged and the vandalism escalated to more severe acts such as arson. This primarily took place in the city but surrounding suburbs were not entirely immune. Property owners unable to sell in the rapidly declining Detroit city housing market would use this night as an excuse to burn down their homes to collect insurance money. These incidents were blamed on Devil's Night hooligans, greatly adding to the notoriety of the night.

The crimes became more destructive in Detroit's inner-city neighborhoods, and included hundreds of acts of arson and vandalism every year.

According to this AP release, “At its peak in 1984, 810 fires were reported in Detroit from Oct. 29 to 31, fueled by, among other things, Devil's Night's growing notoriety and the city's large number of abandoned buildings.”

Even though the number of blazes has dropped off since then, due to buildings having been burnt down already or demolished over the years, and the large number of volunteers and law enforcement patrols that have mobilized through out the city, still “147 fires were reported last year for the three days ending Oct. 31, up from the 113 reported in 2006 and 121 in 2005.”

A new rise not uncannily timed with the spread of the national foreclosure crisis, perhaps. And, as Vergara reminds us, in desperate times people do desperate things, like burn down their own homes for insurance claims, for instance.

Angel’s Night, the activist core that has organized for years on Halloween in Detroit to spook off the burners, is expected to get about 50,000 volunteers to help patrol the streets over the weekend.

They’ve even organized an ADOPT-A-HOUSE IN YOUR NEIGHBORHOOD program, where “Volunteers are asked to adopt a vacant house or commercial building in their neighborhood and watch that building from 6 p.m. to midnight during the three-day Halloween period (October 29-31).” Though, midnight might seem a little early to retire one’s vigilance.

I am not sure I can imagine 800 fires raging across my city simultaneously – even if an intensely crafted performance spectacle, that would still be utterly freaky. Where I live there would be a fire on every block. That’s a little too hell-on-earth here in tiny ass San Francisco. Nor can I imagine the impact fires have had on the Detroit landscape over the years (urban and psychological), or in disaster-stoked LA for that matter; or even the informal settlements around the world where fires from dodgy electricity lines flare up and burn communities to the ground over night.

Fires, man. So primal. Though, in another context, like Burning Man for example, arson is a completely cathartic experience. In fact, arson (in a manner of speaking) is the very point. Let it be no secret, as one who has attended Burning Man many times now since the late nineties, there is absolutely something completely liberating and cleansing, for lack of a better term, in setting your city on fire.

There is intense reflection in flames. Resolution. I never went through any sort of firestarter stage as a kid, more so just inclined to lose my stares for hours in a good campfire, but I do believe, on some profoundly rooted level, fire heals.

But, I’m hardly an expert on the psychology of fire, or where the curiosity of a child setting a fire is satisfied by the act of creating flames themselves, and when that crosses over into some other behavior where fire setting is used as a weapon, of some kind; but I couldn’t be more curious, the mind’s occupation with fire from the phenomenological to cultural to pathological to political and back again.

It might be an interesting project to research: the role of fire in human psychic development, cross-culturally, in relation to space and architecture. In some ways it might not be dissimilar from a fascination with building and demolition, both get at a burning desire for control. I don’t know. Is there an architectural fascination with fire beyond perhaps fetish? Or, is there a secret obsession with architecture in the mind of every pyromaniac? Who know, but, there is something in there to be said for objects as they occupy and dissolve in space, no?

Whatever. Either way, besides all of that, Detroit as a case study for the socio-cultural roots of arson, and not merely the psychological origins, seems deserving of more attention.

[Image: Flint, MI., Photo by Bryan Finoki, 2007.]

Nevertheless, I just found these signs striking. Maybe because the last time I was in Flint Wes told me about prospecting squatters who put For Sale signs with phone numbers in front of abandoned properties to try and swindle down payments on houses they don’t even own; or maybe it was that house with the "Human Sacrifices Needed" billboard plastered to it that sparked my interest here; or all those other lawns that were claimed by signs helping to elect a man by the name of Walling for mayor. The American landscape is such a playground for signs. I am quickly becoming obsessed with the notion of signage and am not sure exactly why. Something to do with the contrast between their literal language and their symbolic vocabulary for imaginary borders, and their various claims to entitlement, like colonial badges of honor, or something, I suppose -- signs are just so very curious.

[Image: Flint, MI., Photos by Bryan Finoki, 2007.]

And in light of an earlier post, I guess I couldn’t resist pointing out Detroit’s Halloween facades here.

According to this recent news dispatch, the number of fires on Halloween has been slightly down so far this year, compared to last.

The city's fire department counted 48 fires as of 3 a.m. Saturday morning, down from 54 the previous year, according to mayoral spokeswoman Meagan Pitts. Of those fires, 29 have been deemed suspicious, though Pitts was cautious to say that doesn't mean they were caused by arson.

But, some other strange thought just occurred to me. I imagined Halloween in Detroit from the point of view of the abandoned buildings themselves – the night the existence of old homes and storefronts, warehouses and informal shelters, are violently threatened by a dispersed mob of so-called “building lynchers” ready to raze their meek and ailing walls for good.

It might be easy to think that all that abandonment is more or less just blight on the surface, urban barricades to further development, debris from the past, and that either torched or demolished the city is better off slashing and burning its deadened landscape. Not that anyone here is espousing random arson as a means for wiping the slate clean, or regenerating urbanism.

But I can’t overlook the potential death of infinite memory that harbors in all these kindling places; the remnants of peoples’ lives that sit idle in these shacks now, like torn pages from some urban scrap book; time capsules of struggle laid out in an architectural graveyard where small and forgotten monuments of race, poverty, struggle, linger on a sprawling slab for vandals and their kerosene joy rides.

An odd proposal: what if the city identified certain buildings beforehand deemed for demolition, but rather than taking wrecking machines to them, they waited until Halloween and used them as a way to funnel and organize the arson towards a planned public ritual of building-burning in a controlled scenario instead? I know that defeats the purpose of vandalism almost entirely (and is probably totally ignorant of the subcultural motives that have fueled Devil’s Night), but I wonder, if the arson were written into the city’s urban planning strategy through the guise of potentially being an art project (as radical and ludicrous as that may sound), could the vandalism be somewhat channeled and defused that way? Further, could the vacant structures somehow be used to create, not just a pyro spectacle for the public (because, aren’t we all fascinated by fire and burning structures, to some extent?), but a more sincere cultural experience, an homage of sorts to the neighborhoods and communities there for whom these buildings have represented, a socio-urban catharsis, giving the decrepit structures and the memories contained within them a more noble death?

I know – sounds absurd – who cares about the death of such abandonment, about what the buildings need? A lot of these buildings hold tremendous value for the people there, with a litany of quiet historic narrative of personal and political struggle inscribed by them. I mean, isn’t architecture (no matter how pithy) the shell translation of cultural and personal memory? What psychological relevance does the Detroit landscape hold in the collective memory of the people there? What does it mean to want to burn one’s neighborhood down, or even preserve the abandonment for that matter; what does that satisfy; is it wrong, or is there an element of release in the arson that is crucial to Detroit’s future healing? I have no idea, I just wonder.

Maybe all of this is just too damned psychodramatic and paganistic and silly sounding, but could Halloween be turned into a night of celebratory tactical demolition, part cityworks’ project, part holiday spectacle, with a touch of cultural release thrown in for good measure? These sites could be the stages of incredible theater, dramas could be enacted at these burnings, stories could be told, ghosts of abandonment could be conjured and put to rest, scars of political struggle could be mended, demons purged, old neighborhoods freed of their psycho-urban wounds; it could be a kind of annual exorcism for Detroit’s collective psyche, a mass architectural funeral for the past.

Or not. This might, of course, actually just be totally ridiculous and inappropriate to even suggest, I am well aware of that, too.

In a book -- Devil's Night: And Other True Tales of Detroit

“The bitter controversy over who is to blame for Detroit's problems may be insoluble, but to my mind, blame is largely beside the point. Detroit will either be helped or it won't. And that decision lies, first and foremost, with those who have the capacity to extend aid.

Money is one answer, but not the only one, and perhaps not the most important. What must come first is an emotional reconciliation that will enable the black polis to rejoin the American family and to accept help without feeling humiliated or being robbed of its political gains. This aid must be given not out of guilt, or fear, but with generosity and good will. If it is forthcoming, Detroit could well become the model for an American racial modus vivendi. If it is withheld, America's first black metropolis - and its white neighbors - may be headed for a Devil's Night that will never see the dawn.”

Indeed, it’s not just that the fires of Devil’s Night should be doused as quickly as they are started, but the cultural significance of what sets them off perhaps needs to be better understood. What is the message in Devil’s Night besides ‘just a bunch of senseless hooligans vandalizing their streets’ every year? What do the fires really mean? Is snuffing them enough of an answer? The fires certainly speak to much more than that.

If the underlying messages of the fires aren’t also heard somehow, then I wonder if Detroit may not just turn out to be a foreboding precursor to flames ignited across the country one day, or the world for that matter – besieged 21st century cities and suburbs driven to the point of burning themselves down, from LA to Paris, Baghdad to Rome.

Admittedly, I know very little about the political conditions that have underwritten the struggles of Detroit, described once as “America’s first Third World city”, but whatever has driven the evolution of the Devil’s Night phenomenon seems like hardly something lost to the past. Should current economic conditions have anything to say about it, and continue to persist on a global scale in devising mass segregations of wealth and poverty, urban and racial divide, then should we be surprised if these fires become new border walls in the future?

6 Comments:

"Admittedly, I know very little about the political conditions that have underwritten the struggles of Detroit,"

The fact that Detroit a Republican mayor since 1961 might be a place to start.

Not that correlation is causation or anything like that.

The other dimension to Devil's Night totally neglected by national media is that until recently the city was extremely slow in demolishing abandoned homes. As one would expect, in marginal neighborhoods, these dwellings attracted all manner of uncivil behavior. It was often the remaining homeowners that took advantage of the fact that firefighters were known to be overcommitment on Devil's Night to burn down the offending structures without fear of public services interfering with the destruction. Thus, what is often portrayed as mindless destruction has in some cases been an act of desperation by individuals abandoned by city government to take back what remains of their neighborhoods.

What a magical explanation. I wouldn't have thought it possible to excuse mass arson and at the same time render everything as the fault of impersonal forces. But there it is. Amazing mentation. Just amazing.

Bryan, a few random thoughts.

About signage . . . last trip to Flint I saw a few "No Copper" signs in doors and windows on occupied houses. I think informing scrappers, others that it's not worth breaking into the house as there's nothing of such obvious immediate value. About the comment from anonymous . . . this is inline with my understandings of Flint. No one knows for sure, but I've been told it's possible that "good citizens" sometimes set nearby abandoned houses on fire, as said by anonymous, "to take back what remains of their neighborhoods." It is the case, in Flint, that houses set on fire are moved to the top of the teardown lists. About Adopt-A-House . . . very interesting, this sort of "ownership" of something abandoned by others. Again, it's not uncommon to see vacant lots mowed by nearby residents in distressed areas of Rust Belt cities I've visited.

I'm remembering a neighborhood meeting in Flint. I tagged along, as one of the agenda items was the scheduling of house teardowns. I assumed that there was going to be complaints about too much tearing down. The opposite was the case -- people wanted more teardowns, wanted to know what was taking so long, where are the bulldozers, they asked.

Also, I know something of your interest in walls, but wondering, in spatial terms only, if there aren't other ways to think about being strategic with fire, in the physical settings you're discussing, without resorting to "walls"? Especially in places, cities, governments where immediate tactics are all anyone has the time to consider.

I like that you're trying to stretch our thinking about what might be, could be thought about, imagined, asked. Right, maybe orchestrated fires, neighborhood rituals, an odd sort of honoring of the lost past within the hard present.

As we've discussed, still I wonder how such a sensibility can be leveraged or worked into reality, as it's coming from others, from above, from you.

Last time in Flint, just driving around for a few hours, I saw four or so burned down houses.

Also, I saw at least four community gardens, first time I saw that in the three summers I've been up there.

More and more I'm questioning what I was thinking when you quoted me last year . . . "If there is life in Flint . . ." It's obvious, there is life, there are committed individuals, good (small) work and works are being done every day.

I have this hazy memory of driving through a trailer park Indian reservation on the Washington state coast. The yards were unmowed and strewn with debris. I saw no one outside, and at every house the shades were tightly drawn. Save for the cars in the driveways, it was difficult to tell which, if any, of these homes was inhabited.

Over the front door of one of them, a large sheet of plywood bore the spraypainted message "Poverty doesnt live here any more."

I grew up in a neighboring suburb of Detroit, and I have to agree with the quote about the lack of racial reconciliation. I think a good portion of the white suburban elites were actually happy to watch the black metropolis collapse. Plenty of hatred to go around.

There is a section in Tom Sugrue's book "The Origins of the Urban Crisis" that discusses a wall built to divide white and black neighborhoods in Detroit during the 1950s. (http://press.princeton.edu/titles/8029.html).

Another type of "wall" that I recall was the stark difference on either side of Alter Road (border btw. Detroit and Grosse Pointe). Driving out of the city and into the suburb, you encountered what might well be thought of as a "green wall" as you passed into the lush tree-lined streets of GP. In the summertime, there is a definite temperature drop as you drive under the trees. Also, Alter Road east of Jefferson runs along a creek. There is (or was) a berm and high fence with barbed wire on the Grosse Pointe side of the creek. Nothing metaphorical about that.

Post a Comment

<< Home