"Prisoner Boxes"

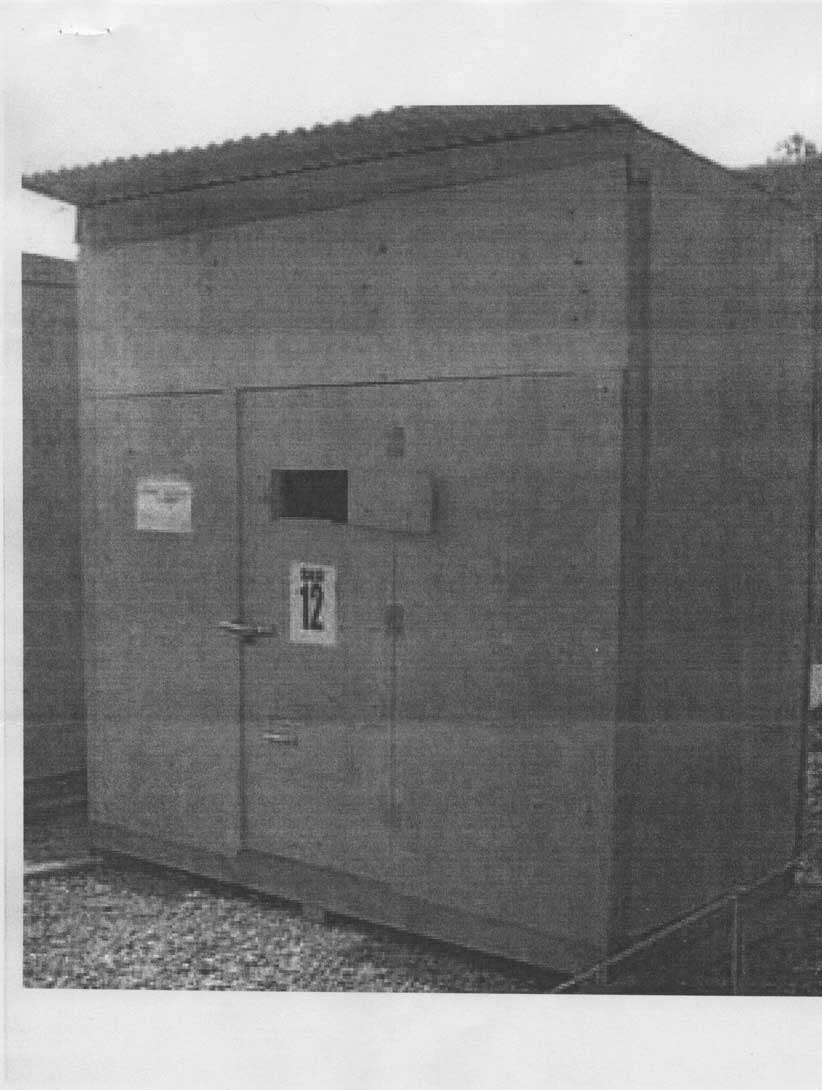

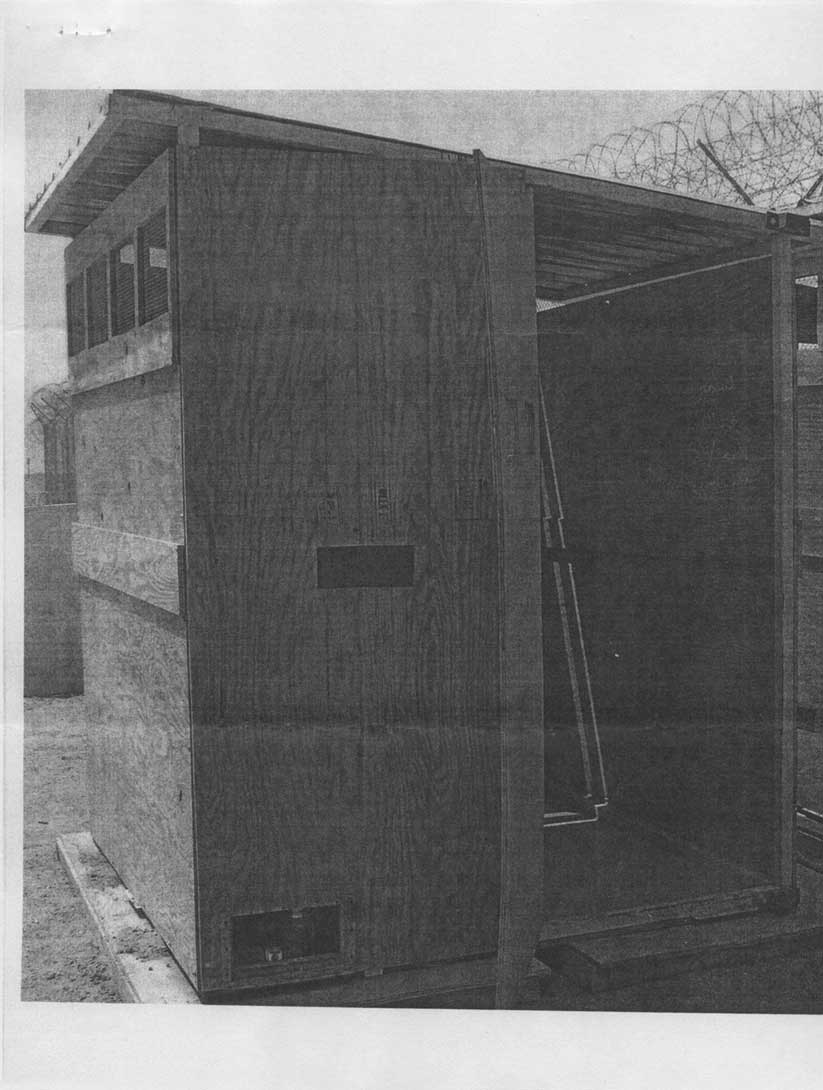

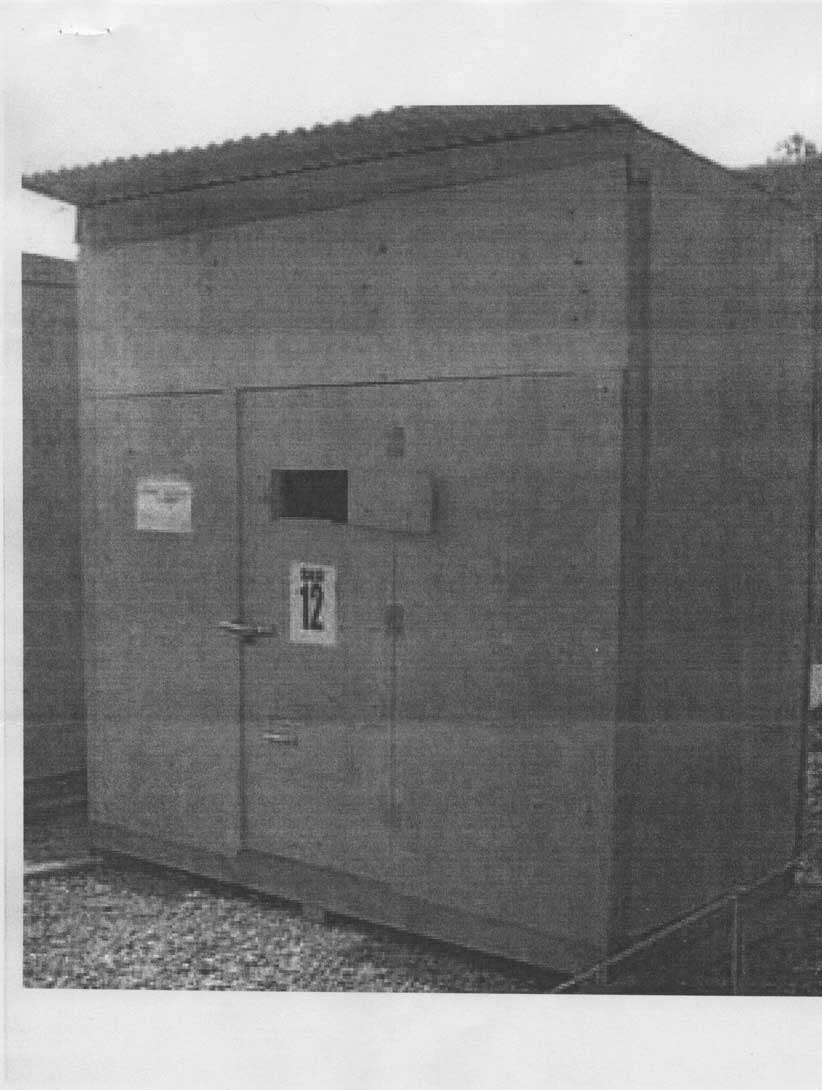

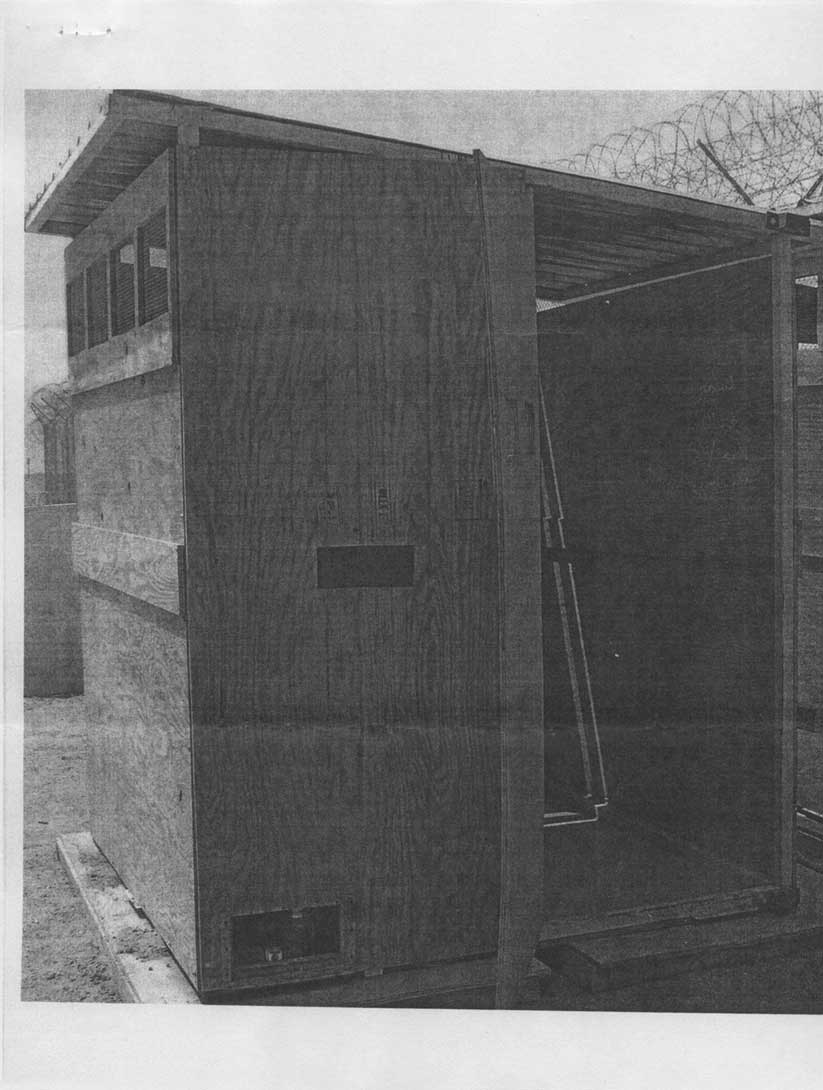

Thanks to one of our readers, some freaky images have come our way. Omar sent me a link to these “wooden imprisonment crates” used in Iraq by American forces to detain insurgents and terrorist suspects.

They were published by Russ Rick at Memory Hole only a few days ago. After he spotted a mention of these crates -- referred to as “prisoner boxes” -- in a February 2005 issue of Vanity Fair (which unfortunately I cannot locate online), he filed a Freedom of Information Act request with the U.S. Central Command demanding photographs of the boxes. And it’s kind of amazing, actually. Nine and a half months later, CentCom came through and sent him what you see here.

First and foremost, the prisoner boxes, in my opinion, are another stark reminder that torture is, in and of itself, a space; that is, that torture happens within a space as much as it defines a space – even if it is out in the open for all to see. Sometimes, however, only the simplest rudimentary unit of space is all that is required to constitute torture.

The prisoner box is anything but elaborate. Look at it, looks like a campsite outhouse. It is far from a specialized torture module of any kind. It does not have the sadistic anatomical engineering of an iron maiden, or even the spectacular proximity of a public thrashing where civic space has been converted into an arena for the collective participation in cruelty. It is very simply and adequately, a box made of plywood. It could be useful for so many things. However, when a person is made to sit inside one in the 100+ degree summer heat of Iraq all day long, week after week – it is then probably the cheapest human oven ever designed. It becomes torture space in its simplest form, reduced to its barest essence; the prisoner box as a minimal cubic space of biopolitics.

In some ways, it is the perfect architectural co-conspirator with that of the space of waterboarding. Whereas in that scenario, all that is necessary is a wooden plank with shackles to rest the body so that an appropriate dousing of water can be poured over the face to simulate the effect of drowning. Here, the wooden planks minus the shackles enforce the total absence of water, instead increasing dehydration and the cooking of the brain. They are both torture products of the same barebones ilk. Although, with the prisoner box there are no other props needed. Torture is the space itself.

And the fact that they’re “boxes” – I mean, the anonymous and ephemeral implications of “torture crates” are even more harrowing than any elaborate torture architecture, if you ask me. Because, as sick as a sophisticated torture chamber may be, at least it still perceives the subjects of torture as something worthy of greater attention. But to just file people away inside these desert closets to idly rot in the sun – in the basest form of torment – is to suggest the body is not even worth a dignified torture, if such dignity could exist.

There is also something about "torture crates" in the age of a global economy, too, that is particularly creepy. It hints at a kind of industry, torture in the form of shipping and receiving; an import/export business. But, I’ve gone over this thought already before.

I can’t think of any nature of space being more political than torture space -- except for perhaps the womb.

Anyway, I guess what I find just as spooky as the existence of the boxes themselves is the ease of their potential erasure from the landscape. When I think about a spatial legacy of the ‘war on terror’, architectural objects and relics that we may look back upon, say, 200 years from now, as a forensic geography of the ‘war on terror’’s narrative of torture, perhaps the way we look back upon the ancient remains of war from the Dark Ages as artifacts of barbarism; or even the more modern ruins of the Cold War as living museums of institutional paranoia – these “prisoner boxes” probably won’t last. They are this way the perfect epitome of the ‘war on terror’’s environmental imprint, or the lack thereof, in that they are made fleeting, detached, improvised, totally exceptional, politically and physically; meaning, they are designed to technically no longer exist once they've fulfilled their usefulness. Unlike the colossal shells of megaprisons, they are disappearing acts, blips on the future radars of human rights organizations around the world; collapsible serial boxes for an evidenceless trace of the ‘war on terror’ architectural secrecy.

I don’t’ know, you must forgive the excessive overspeak here, but perhaps they may try to look back one day and say, without these grainy images, that torture never truly existed, or just extend the debate about torture’s definition ad nauseam. And certainly, these images alone are not evidence of torture, per se, but at least they help undermine the politics of visuality that keeps the spaces of torture hidden; at least they enable us to see all that is required, or not as the case may be, to spatialize torture. So, well done Russ.

[All Images were obtained and published by Russ Rick on July 23, 2008. Technical note: These photographs were released as black and white print-outs by the US Central Command on 10 Nov 2005 in fulfillment of FOIA request #2005-085, filed by Russ Kick on 27 Jan 2005.]

(And thanks again to Omar for bringing this to our attention.)

Related: Torture Space: Architecture in Black; Shipping Justice; Carceral Wombs ; In the Business of Blast Walls.

They were published by Russ Rick at Memory Hole only a few days ago. After he spotted a mention of these crates -- referred to as “prisoner boxes” -- in a February 2005 issue of Vanity Fair (which unfortunately I cannot locate online), he filed a Freedom of Information Act request with the U.S. Central Command demanding photographs of the boxes. And it’s kind of amazing, actually. Nine and a half months later, CentCom came through and sent him what you see here.

First and foremost, the prisoner boxes, in my opinion, are another stark reminder that torture is, in and of itself, a space; that is, that torture happens within a space as much as it defines a space – even if it is out in the open for all to see. Sometimes, however, only the simplest rudimentary unit of space is all that is required to constitute torture.

The prisoner box is anything but elaborate. Look at it, looks like a campsite outhouse. It is far from a specialized torture module of any kind. It does not have the sadistic anatomical engineering of an iron maiden, or even the spectacular proximity of a public thrashing where civic space has been converted into an arena for the collective participation in cruelty. It is very simply and adequately, a box made of plywood. It could be useful for so many things. However, when a person is made to sit inside one in the 100+ degree summer heat of Iraq all day long, week after week – it is then probably the cheapest human oven ever designed. It becomes torture space in its simplest form, reduced to its barest essence; the prisoner box as a minimal cubic space of biopolitics.

In some ways, it is the perfect architectural co-conspirator with that of the space of waterboarding. Whereas in that scenario, all that is necessary is a wooden plank with shackles to rest the body so that an appropriate dousing of water can be poured over the face to simulate the effect of drowning. Here, the wooden planks minus the shackles enforce the total absence of water, instead increasing dehydration and the cooking of the brain. They are both torture products of the same barebones ilk. Although, with the prisoner box there are no other props needed. Torture is the space itself.

And the fact that they’re “boxes” – I mean, the anonymous and ephemeral implications of “torture crates” are even more harrowing than any elaborate torture architecture, if you ask me. Because, as sick as a sophisticated torture chamber may be, at least it still perceives the subjects of torture as something worthy of greater attention. But to just file people away inside these desert closets to idly rot in the sun – in the basest form of torment – is to suggest the body is not even worth a dignified torture, if such dignity could exist.

There is also something about "torture crates" in the age of a global economy, too, that is particularly creepy. It hints at a kind of industry, torture in the form of shipping and receiving; an import/export business. But, I’ve gone over this thought already before.

I can’t think of any nature of space being more political than torture space -- except for perhaps the womb.

Anyway, I guess what I find just as spooky as the existence of the boxes themselves is the ease of their potential erasure from the landscape. When I think about a spatial legacy of the ‘war on terror’, architectural objects and relics that we may look back upon, say, 200 years from now, as a forensic geography of the ‘war on terror’’s narrative of torture, perhaps the way we look back upon the ancient remains of war from the Dark Ages as artifacts of barbarism; or even the more modern ruins of the Cold War as living museums of institutional paranoia – these “prisoner boxes” probably won’t last. They are this way the perfect epitome of the ‘war on terror’’s environmental imprint, or the lack thereof, in that they are made fleeting, detached, improvised, totally exceptional, politically and physically; meaning, they are designed to technically no longer exist once they've fulfilled their usefulness. Unlike the colossal shells of megaprisons, they are disappearing acts, blips on the future radars of human rights organizations around the world; collapsible serial boxes for an evidenceless trace of the ‘war on terror’ architectural secrecy.

I don’t’ know, you must forgive the excessive overspeak here, but perhaps they may try to look back one day and say, without these grainy images, that torture never truly existed, or just extend the debate about torture’s definition ad nauseam. And certainly, these images alone are not evidence of torture, per se, but at least they help undermine the politics of visuality that keeps the spaces of torture hidden; at least they enable us to see all that is required, or not as the case may be, to spatialize torture. So, well done Russ.

[All Images were obtained and published by Russ Rick on July 23, 2008. Technical note: These photographs were released as black and white print-outs by the US Central Command on 10 Nov 2005 in fulfillment of FOIA request #2005-085, filed by Russ Kick on 27 Jan 2005.]

(And thanks again to Omar for bringing this to our attention.)

Related: Torture Space: Architecture in Black; Shipping Justice; Carceral Wombs ; In the Business of Blast Walls.

5 Comments:

Another fantastic post. I have been reading your blog for a while now and always enjoy both the images and the thoughtful commentary.

Thanks!

... Sorry for the recent ongoing hiatus.

Bryan, I like the shades of Arendtian (Eichmann-esque?) banality threaded into your observations. I also wonder at the distributed functioning of panoptic elements; at how the the innate invisibility of these structures can be reconciled with the invisible links that bind them together across material, human and cognitive planes.

Yes, sure, absolutely. The banality of them, as if they were made to be seen as military latrines, does perhaps provide them a camouflage to those who are not privy to what they really are; and, to those who do, they still seem normalized through their structure which might make them much more easily digestible for those personnel who are subjected to them. It might be much easier to function in and amongst them if they are treated as normal spaces and not specialized or highly secretized. ‘out of sight, out of mind,’ seems enforced to a degree here by the non-descript qualities of their construction and placement, which is all of course part of larger strategies to situate and weave these kinds of architectures of control under our noses, behind our ears, right in front of our faces, domesticated; architectural banality as disguise.

is that what you were getting at Michael?

Lol... yes. I just liked the subtle historical analogy - I think it was "the cheapest human oven ever designed" that triggered the Arendt/Eichmann meme for me, though you've written it in elsewhere, more overtly.

My point (or query) about control/invisibility/networks was off in a different direction, though. When we think of networks and networked organizations, we think of nodes and clusters connected by links of varying kinds: relationships, interactions, exchange rituals, mobility circuits, and so on.

But when those nodes are invisible, in the way that you've described them, what then? If invisibility in this sense is a spatial inversion, an obverse reality, then what does that mean for the other elements of the network with which they interact? What's the character and consequence of their interface?

Post a Comment

<< Home