2 Books on Ireland's Haunted Walls

Sean O'Hagan, writing for the Guardian, points out in a nostalgic little article entitled All along the watchtowers... the symbolic timing of photographer Jonathan Olley's recent publication Castles of Ulster. "As the Troubles slip further into history" he writes, "the black-and-white photographs of Northern Ireland's police stations, army barracks and watchtowers is a record of what might be called 'indigenous Troubles' architecture'," and whose only remains, he warns, may one day be this collection of brilliant images.

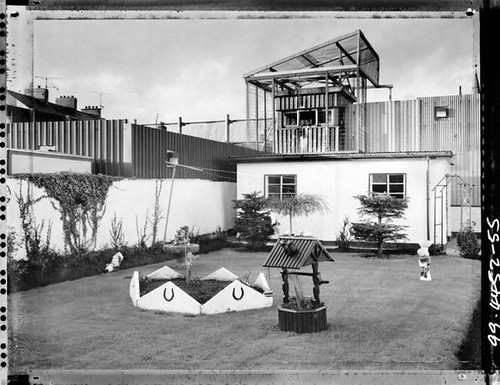

Of course, I haven't seen Olley's book yet, and must admit -- I don't know nearly enough about this slice of Irish history as I should -- but just check out these photographs on his website. Could the studded walls, paranoiac towers and imprisoned outposts of Ireland's troubled past have been captured any more perfectly?

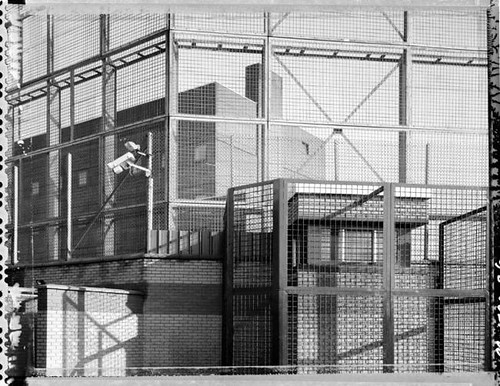

[Image: The 'Borucki Sanger', Crossmaglen, South Armagh, Northern Ireland, UK. Photo by Jonathan Olley.]

Anyway, because O'Hagan came of age in Armagh (a small city in N. Ireland), he tells us, he experiences a precarious nostalgia for the Castles of Ulster today, as it seems like many of the residents there do, too. Even though the Castles induced a "feeling of trepidation" and "sense of oppression that seemed built into the concrete and steel," they were -- despite this psychological scarring -- the quintessential landmarks of his childhood.

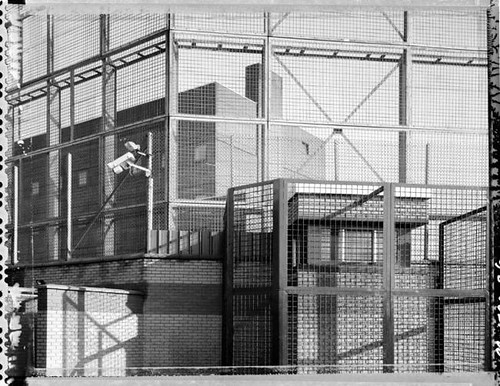

[Image: Photo by Jonathan Olley.]

Could the unfortunate link between architecture and memory ever be more apparent? O'Hagan describes some of them:

While Olley's photos are evidence of a distinctly terrorized Irish landscape the more frightening truth about them for me is that they could almost be, in so many regards, the filmic traces of any number of places around the world today.

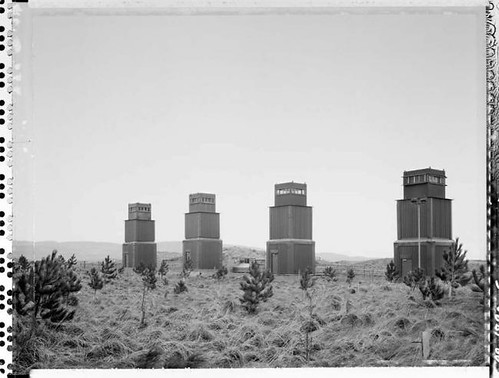

[Image: Photo by Jonathan Olley.]

If we were just to focus on the brutish walls and violent features of defensive accouterment, it wouldn't be that inconceivable to mistake N. Ireland for, say, parts of Jerusalem or Gaza, or even Johannesburg, maybe downtown Manilla for that matter - possibly a neighborhood in central Egypt or Lebanon; conflicted places which are facing some of their own most cruel histories with political walls and entangled battle urbanism still today.

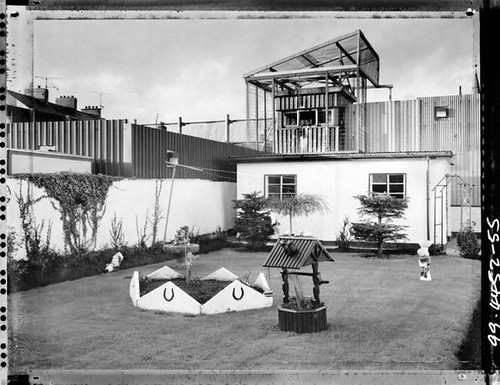

[Image: RUC police station, Grsvenor Road, central Belfast, County Down, Northern Ireland, UK. Photo by Jonathan Olley.]

Just as these crude building cages, barbed towers and hilltop bunkers could ultimately meet their physical fate if North Ireland officials continue to go the direction of total demolition and indigenous Troubles' architecture erasure, these shameful structures still manage to tragically appear elsewhere in the world along other fissures of an even larger more volatile urban geopolitical faultline. So while we celebrate Ireland's progress for finally transcending such a haunted architectural past, the day also dawns a stark reminder of parallels that can be drawn to other locales unfortunatley enduring the legacy of a similar urbanism of violence right now, which are equally reflected in these images.

Which actually makes me think of a very harrowing prospect in the future - for some heavily financialized global fortress scrap market where perhaps Haliburton comes to operate an international conglomeration of embattled building parts collectors through out different conflict zones - as an urbanistic trading ring for various national armies and nascent paramilitary outfits who are eager to make their streets all the more impenetrable.

[Image: Photo by Jonathan Olley.]

So, as Ireland decides to retire much of its infamous barricades other countries come forward to bid on them, and one day the 'Borucki Sangar' or the one at Crossmaglen ends up re-deployed somehwere in Kabul or Kashmir. Memory-charged sniper towers and remnants of police barracks from Armagh would be won by Hezbollah through some sort of proxy auction. Meanwhile, Haliburton's dismantling crews perpetually hover around war zones chomping at the bit to profit off of both a territory's urban de-militarization as well as another place's re-militarization. As if military urbanism were a natural element of the modern environment to be traded like anything else - as just another architectural resource on the planet. So, ironically enough, The Great Wall of China could actually one day be completely reconstituted along the entire 2,000 mile stretch of the U.S./Mexico border. How scary would that be?

Absurdly unimagineable, I know, but sometimes I wonder - what will happen 400 years from now to all of these more or less shameful constructs?

However, given today's spread of urban warfare the demand for re-militarization seems like it would always outweigh that for de-militarization, sadly. So, I'm not exactly sure where that puts this recycled fortress thing.

[Image: Photo by Jonathan Olley.]

Though, one day, like ridiculously coveted art objects -- or some kind of new precious landscape antiques -- these random historic barriers, memorable gates and high-valued corner turrets would increase in both capital and cultural value, as they gradually become bizarre obsessions of connoisseurship - like futuristic military urbanism trophies, if you will. Defense forces and security real-estate buffs all over would secretly engineer curious moments of regional peace and stability simply in order to have the historic walls de-commissioned and collected for their commodified posterity, and then would hire teams of a-political sell-out architects to fancy an epic border wall museum that promises to stretch tourists, migrants, soldiers and secret operatives together along an incredible stroll overseas, through jungles, across freshly snow-capped desert peaks, through thousands of border towns, down patrolled valleys, through restricted tunnels, past classified military installations, all the way to the invented frontiers of some endless new conflict.

The world's current scattered output of military urbanism bartered for and traded, and eventually re-devised into a single dominant armored structure that would later on be owned mostly by Trump's great great grand-daughter, a memory-deprived history enthusiast with a half-baked interest in architecture and delusional notions about global tourism development.

Or, maybe not. Whatever, it's a dismal little scenario, I'll be the first to admit: the globalization of a military urbanism parts market.

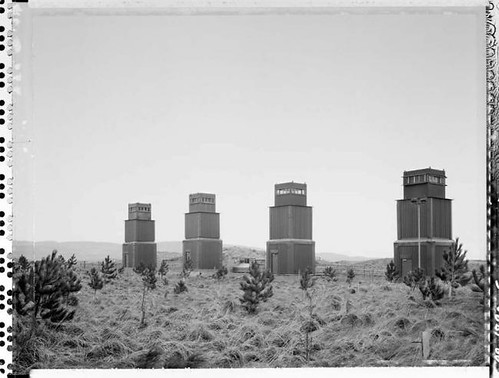

[Image: Magilligan Ranges, Magilligan Point, County Londonderry, Northern Ireland, UK. Photo by Jonathan Olley.]

Alright, since you've had enough of my babble here are a couple of other articles worth reading on the urban remnants of the Troubles' and what it means for the people who live there today after enduring such a skittish epoch.

The Troubles: a walking tour

Fragile calm behind Ulster's 'peace walls'

The other book I wanted to quickly mention is The Maze by Donovan Wylie, which looks incredible, if you are into this sort of thing.

[Image: The Maze, by Donovan Wylie, via Slate.]

Let me quote the book's description:

[Image: The Maze, by Donovan Wylie, via Slate.]

And indeed his photos are amazing, as you can find many of them right here on Slate. Unfortunately, there aren't more detailed captions to go with them, but the images are so powerful on their own I am not even sure what more needs to be said.

[Image: The Maze, by Donovan Wylie, via Slate.]

See them all for yourself.

(Thanks Nama and Geoff!)

Of course, I haven't seen Olley's book yet, and must admit -- I don't know nearly enough about this slice of Irish history as I should -- but just check out these photographs on his website. Could the studded walls, paranoiac towers and imprisoned outposts of Ireland's troubled past have been captured any more perfectly?

[Image: The 'Borucki Sanger', Crossmaglen, South Armagh, Northern Ireland, UK. Photo by Jonathan Olley.]

Anyway, because O'Hagan came of age in Armagh (a small city in N. Ireland), he tells us, he experiences a precarious nostalgia for the Castles of Ulster today, as it seems like many of the residents there do, too. Even though the Castles induced a "feeling of trepidation" and "sense of oppression that seemed built into the concrete and steel," they were -- despite this psychological scarring -- the quintessential landmarks of his childhood.

[Image: Photo by Jonathan Olley.]

Could the unfortunate link between architecture and memory ever be more apparent? O'Hagan describes some of them:

From the hilltops of South Armagh and County Down, the British army had a panoramic, 360-degree view and surveillance equipment that could see clearly into the sitting rooms of houses five miles away. Listening devices tracked the conversations of motorists queuing at the security checkpoints far below.

Around South Armagh, a predominantly republican area, the police state manifested itself most oppressively in Crossmaglen's RUC station and barracks, the infamous 'Borucki Sangar' (a sangar is a temporary fortification), which loomed, stark and medieval, in the middle of a row of shops and pubs on the main square, its watchtower all-seeing.

As the buildings themselves disappear, these images may well become one of few testaments to their presence, a rare glimpse of a not-too-distant past that is already being airbrushed for posterity.

While Olley's photos are evidence of a distinctly terrorized Irish landscape the more frightening truth about them for me is that they could almost be, in so many regards, the filmic traces of any number of places around the world today.

[Image: Photo by Jonathan Olley.]

If we were just to focus on the brutish walls and violent features of defensive accouterment, it wouldn't be that inconceivable to mistake N. Ireland for, say, parts of Jerusalem or Gaza, or even Johannesburg, maybe downtown Manilla for that matter - possibly a neighborhood in central Egypt or Lebanon; conflicted places which are facing some of their own most cruel histories with political walls and entangled battle urbanism still today.

[Image: RUC police station, Grsvenor Road, central Belfast, County Down, Northern Ireland, UK. Photo by Jonathan Olley.]

Just as these crude building cages, barbed towers and hilltop bunkers could ultimately meet their physical fate if North Ireland officials continue to go the direction of total demolition and indigenous Troubles' architecture erasure, these shameful structures still manage to tragically appear elsewhere in the world along other fissures of an even larger more volatile urban geopolitical faultline. So while we celebrate Ireland's progress for finally transcending such a haunted architectural past, the day also dawns a stark reminder of parallels that can be drawn to other locales unfortunatley enduring the legacy of a similar urbanism of violence right now, which are equally reflected in these images.

Which actually makes me think of a very harrowing prospect in the future - for some heavily financialized global fortress scrap market where perhaps Haliburton comes to operate an international conglomeration of embattled building parts collectors through out different conflict zones - as an urbanistic trading ring for various national armies and nascent paramilitary outfits who are eager to make their streets all the more impenetrable.

[Image: Photo by Jonathan Olley.]

So, as Ireland decides to retire much of its infamous barricades other countries come forward to bid on them, and one day the 'Borucki Sangar' or the one at Crossmaglen ends up re-deployed somehwere in Kabul or Kashmir. Memory-charged sniper towers and remnants of police barracks from Armagh would be won by Hezbollah through some sort of proxy auction. Meanwhile, Haliburton's dismantling crews perpetually hover around war zones chomping at the bit to profit off of both a territory's urban de-militarization as well as another place's re-militarization. As if military urbanism were a natural element of the modern environment to be traded like anything else - as just another architectural resource on the planet. So, ironically enough, The Great Wall of China could actually one day be completely reconstituted along the entire 2,000 mile stretch of the U.S./Mexico border. How scary would that be?

Absurdly unimagineable, I know, but sometimes I wonder - what will happen 400 years from now to all of these more or less shameful constructs?

However, given today's spread of urban warfare the demand for re-militarization seems like it would always outweigh that for de-militarization, sadly. So, I'm not exactly sure where that puts this recycled fortress thing.

[Image: Photo by Jonathan Olley.]

Though, one day, like ridiculously coveted art objects -- or some kind of new precious landscape antiques -- these random historic barriers, memorable gates and high-valued corner turrets would increase in both capital and cultural value, as they gradually become bizarre obsessions of connoisseurship - like futuristic military urbanism trophies, if you will. Defense forces and security real-estate buffs all over would secretly engineer curious moments of regional peace and stability simply in order to have the historic walls de-commissioned and collected for their commodified posterity, and then would hire teams of a-political sell-out architects to fancy an epic border wall museum that promises to stretch tourists, migrants, soldiers and secret operatives together along an incredible stroll overseas, through jungles, across freshly snow-capped desert peaks, through thousands of border towns, down patrolled valleys, through restricted tunnels, past classified military installations, all the way to the invented frontiers of some endless new conflict.

The world's current scattered output of military urbanism bartered for and traded, and eventually re-devised into a single dominant armored structure that would later on be owned mostly by Trump's great great grand-daughter, a memory-deprived history enthusiast with a half-baked interest in architecture and delusional notions about global tourism development.

Or, maybe not. Whatever, it's a dismal little scenario, I'll be the first to admit: the globalization of a military urbanism parts market.

[Image: Magilligan Ranges, Magilligan Point, County Londonderry, Northern Ireland, UK. Photo by Jonathan Olley.]

Alright, since you've had enough of my babble here are a couple of other articles worth reading on the urban remnants of the Troubles' and what it means for the people who live there today after enduring such a skittish epoch.

The Troubles: a walking tour

Fragile calm behind Ulster's 'peace walls'

The other book I wanted to quickly mention is The Maze by Donovan Wylie, which looks incredible, if you are into this sort of thing.

[Image: The Maze, by Donovan Wylie, via Slate.]

Let me quote the book's description:

For nearly 30 years, the Maze prison, 10 miles outside Belfast, Northern Ireland, played a unique role in the Troubles. Built in 1976 to house terrorist prisoners, it became a microcosm of the struggle between loyalists and republicans. It was the scene of violent protests, hunger strikes, mass escapes, and deaths of both prisoners and prison staff. In September 2000, under the terms of the Good Friday Agreement, the prison was closed, and today, nothing but the H-blocks remain. In 2003, the Northern Ireland Prison Service gave Donovan Wylie exclusive permission to photograph the complex without supervision. The result is a book that aims to document the place and to give the viewer an experience of the psychological impact of being inside the Maze.

[Image: The Maze, by Donovan Wylie, via Slate.]

And indeed his photos are amazing, as you can find many of them right here on Slate. Unfortunately, there aren't more detailed captions to go with them, but the images are so powerful on their own I am not even sure what more needs to be said.

[Image: The Maze, by Donovan Wylie, via Slate.]

See them all for yourself.

(Thanks Nama and Geoff!)

3 Comments:

Hey Bryan, I grew up on the border and spent a lot of my childhood in NI and I have no nostalgia whatsoever for this architecture- they were fearful and very dangerous places in the mind of a kid and an adult. I agree wholeheartedly that these images are the negatives of so many sorry situations today- and there is a lesson here and that is for all the perceived permanence of form and material - concrete ,metal, wire, walls whatever, it won't be there forever...someday that bloody wall in Palestine will be crushed and they'll use the rubble to make roads (or more likely to sell to tourists)...the lesson here is always have hope, and I mean that sincerely. The majority of the bases have been removed and I believe this is a good thing, some should be kept of course, these kind of structures are touchstones to a darker time, to remembrance. Today these bases are harmless, impotent without their soldiers- what we need focus our energy on in Northern Ireland is removing active architecture and planning which encourages separation - our 'peacelines' which are still doing the same job they did 30 years ago, things are slowly getting better but it helps if you can actually see your neighbour.

all the best

mick

mick

thanks for taking the time to comment i appreciate your note.

you are absolutely right, a lot of the divisions and the bordering happen in far less obvious and through much more institutional mechanism. that is, the border is the product of certain legal means that have become so normative in our daily planning process. it puts the border virtually everywhere now, in the city's DNA.

thanks again, great point. the real border is in the planning dept, the real estate market,

bryan

Hey Brian, no problem, if I could I'd just like to follow this up with a plug for my buddies at www.seamlessterritory.org ; In relation to what we were just talking about, these guys work towards a world where national territory is not scattered into ethnic and socio-economical enclaves through planning + architecture .....

all the best

mick

p.s your blog is great

Post a Comment

<< Home