Peering into the Arenas of War

[Image: "Chicago" is an Israeli Defense Force urban warfare training facility in Israel, photographed by Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin.]

In the latest issue of New Left Review, Stephen Graham (whom I will be featuring in a more in depth interview here in the upcoming weeks) takes us on a tour of the surreal – and more often than not, all-too-real – hybrid geographies of the Pentagon’s warfare-simulation industrial-complex that is gearing up American soldiers for an indeterminate future-long battle in the world’s urban centers.

“A hidden archipelago of mini-cities is now being constructed across the U.S. sunbelt,” he writes, “presenting a jarring contrast to the surrounding stripmall suburbia” where entire urban replications of Third World cityscapes are also rising out of the deserts of Kuwait and Israel, the downs of Southern England, the plains of Germany and the islands of Singapore.

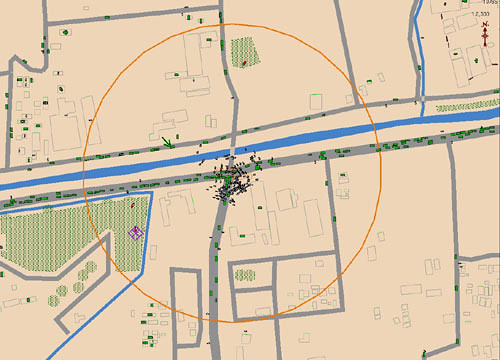

[Image: "Mock Iraqi Villages in Mojave Prepare Troops for Battle," New York Times, 2006]

You’ve no doubt read about some of these places before, perhaps even here as I have mentioned a few, but for those who haven’t – these aren’t your scrappy run-of-the-mill warehouse-sized training modules with a few ramshackle rooms and actors set up to mimic a hostile situation. No, hardly. These secretive camps occupy vast tracts of outback acreage all over the world, featuring literally hundreds of built structures, thousands of actors, not to mention smaller details like having the call-to-prayer looped on an audio tape, or an assortment of chemical vapor machines to simulate the fetid stenches of death.

“In a mirror-image reversal of the more familiar global marketing contests in which cities parade their gentrification, cultural planning and boosterism, here the marks of success are decay and an architecture of collapse.”

[Image: Baghdad, USA, Wired Magazine, June 2006, photo by Jay L. Clendenin.]

It is an industry of controlled destruction, calculated architectural annihilation -- there are houses permanently left in ruins, bridges repeatedly built in order to be demolished, Mosques that become shooting ranges, trees that were never planted but rather scorched and grown to burn; mock explosions occur that could only be operated by Hollywood’s finest effects supervisors; and there are even rats and cows that have been imported while manmade swamps swim with thousands of toy snakes. We are talking entire theme-camps of war where the boundaries between reality and simulation have become so ambiguously blurred that practicing soldiers have been known to lose all perspective on which is which, as war and training become all the more seamlessly one and the same.

[Image: Baghdad, USA, Wired Magazine, June 2006, photo by Jay L. Clendenin.]

“Unmarked on maps, and largely unnoticed by urban-design, architecture and planning communities, these sites constitute a kind of shadow global-city system. They are capsules of space designed to mimic the strategic environment of the ‘feral city’, as one U.S. military theorist has called it—now seen as a critical arena for future wars.”

Graham goes on to brief us on the shifts in doctrine that began to percolate after WWII realizing that future wars would no longer be solely fought from the skies with a superior Air Force casting foreign cities as mere targets, but how the new battlefield would become an increasingly intense urban engagement with the Third World as it continued to undergo dramatic urbanization through out the century, while also remaining disconnected from the social infrastructure of the globalized First world.

“To address future ‘Military Operations on Urban Terrain’ training needs, the RAND team recommendations include the construction of four new ‘cities’, with more than 300 structures each. By 2010, the Pentagon plans to have over sixty MOUT training zones around the world. While some will be little more than air-portable sets of containers, others will be extensive sites that mimic whole city districts, with ‘airports’ or surrounding ‘countryside’.”

[Image: When War Games Meet Video Games, Wired Magazine, 2004.]

Pointing out several arenas of war that have already set a certain precedence, we learn that the Zussman Village at Fort Knox, Kentucky is “One of the most important new urban-warfare training facilities” in the mix. It is a 30-acre sprawl of $13 million translated into a quasi-city designed for the sole purpose of being attacked over and over again. There are also some spectacular camps like Fort Wainwright in Alaska, and the prominent training center on the U.S. Baumholder Base in Germany. The biggest U.S. urban-warfare complex of them all, however, is the continually expanding Joint Readiness Training Center at Fort Polk, Louisiana. “Eighteen mock-Iraqi villages are being constructed in this 100,000-acre site.”

Continuing to cite the RAND report, Graham tells us that “the most ambitious suggestion” targets California at the Marines’ Twentynine Palms Base where the aim is to construct “a 20 x 20 km ‘mega-MOUT’ complex” that “incorporates a complete 900-building town” in the California desert, with an estimated cost of $330 million and that could be operational by 2011. “Such a complex would allow an entire brigade to simulate taking a large Iraqi town, including port and industrial facilities, with unprecedented levels of realism.” The report also looks at garrisoning abandoned sites and structures throughout the country: abandoned factories, strip malls, schools, hospitals and entertainment complexes. There is an old copper-mining town in New Mexico that has apparently been used to perfect the art of the suburban raid, an outfit that even employs the few remaining residents there as actors.

[Image: The Urban Terrain Module (UTM), photo via techrizon.]

In addition to the unmistakably real places of the MOUT agenda, his article also rounds up several examples of where training has taken to the virtual domains of city-making and city-conquering. There is the ‘Urban Terrain Module’ at Fort Sill in Oklahoma, for example, and of course, the ‘Urban Resolve’ project, put together back in 2004 to create an unparalleled virtual model of almost the entirety of Iraq, with scaled cities and buildings that boast being within 1 meter of perfect accuracy. There are several other projects Graham discusses, not to mention the plethora of video games which have advanced both a technological profundity for depicting the urban battlefield, even engaging it in some way, as well as an equally dangerous vehicle for propelling military propaganda which also demonstrate “the extent of the American entertainment industry’s commitment to ‘a culture of permanent war.’"

[Image: "Chicago" is an Israeli Defense Force urban warfare training facility in Israel, photographed by Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin.]

All of these urban-warfare simulations combined, however, work together as a kind of larger landscape collective, a hybrid-geography of “complex and self-reinforcing connections between war and entertainment” which serve to devise an alarming spatial complicity “by collapsing the real with the artificed, to the extent that any simple boundary between the two disappears.” In the end, Graham’s argument shows how the only role for Arab cities in the eyes of the west seems to be "as a terrain for urban war.”

Unfortuantely the article War and the City isn't online yet, but it should be in the next few weeks, I think, so keep your eyes out for it.

Also check out: The "Village"; Tracking Blackwater in Potrero; Sim Baghdad; War Room; Peripheral Milit_Urb 5; Cities Made by War; Good Buildings, Bad Buildings; A miniature city waiting for attack; War Play

2 Comments:

The pictures ARE awesome. As an aspiring field intelligence officer, the value of "train the way you fight" isn't lost on me. Far from being "pretend tactics and roleplaying," these are legitimate methods of training. With proper buy-in from all involved, the experiences a soldier learns in Baghdad, USA allow him to respond quicker and in a more controlled fashion in Baghdad, Iraq.

But does anyone else find it slightly disturbing that a facility not due for completion for another four years is designed specifically to mimic 400 square kilometers of Iraq? Realistically (if the Democrats don't win this squabble), we MIGHT still be there then- but I sure don't want to THINK that. And what if we're not? That's ridiculous amounts of money down the train.

What we need instead are agile training centers that don't refer to any specific enemy or can be easily adapted. This is Cover-Your-Ass planning- who says the next battle will be in a desert?

Sorry, I am so late on this.

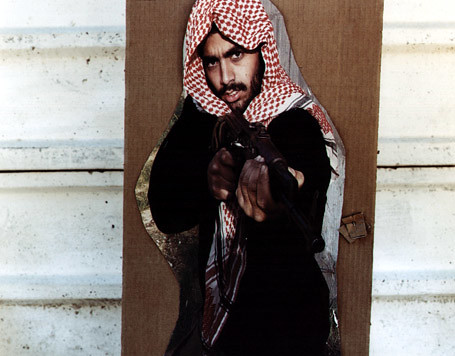

I think Graham would suggest that the main issue is not necessarily the usefulness of these facilities themselves (though, there are many concerns there as well), but rather how these places are used to construct a demonic view of the Arab world, its land and its peoples.

These facilities aren’t created neutrally in that sense, but rather have been devised in such a way as to generate a more widespread suspicion of the Arab community, which has been viewed by the west since time began as a barbaric and somewhat less evolved human population, that must be tamed or domesticated by the righteous western world.

The concern is how these places play into that ‘imaginary geography’, where the projections of an ‘Us’ and a ‘Them’ are further reinforced, where the process of a certain “othering” of the foreign place unfolds in the very tenets of our own social orthodoxy, how landscapes are racialized. More simply put, I worry about the ways in which these places operate as a deeper progandistic machine for spreading fear of the Arab world, and ultimately how they help to rally support for the ‘war on terror’ and for the occupation of the Middle East. These facilities aren’t just about training generic soldiers for a generic war. They are cast in contexts which have the effect of shaping much more important cultural views of the Arab community.

It is more or less about the psychological and cultural implications of the way these places operate, the imprints they leave on a collective imagination about how we should or should not view and treat the Arab world. These places have repercussions beyond just the soldiers who use them; the video games that serve as the equivalent demonstrate this dehumanizing depiction of the Arab world in a more proliferated societal way. It’s an overall dangerous construction of a projected landscape of foreign place. Ultimately how we recreate place in our minds and imagination suggests how we will treat it when we get there. Yes, they are training for warfare, but – that doesn’t mean there shouldn’t be a certain degree of consciousness in there about how we are engineering our soldiers to pre-experience, if you will, the Arab world.

Post a Comment

<< Home