Migrant Structures

I recently wrote an article for Inhabitat on Migrant Structures, which was posted fittingly enough on July 4th. You can read the article here, though I am reposting it on Subtopia with some added research I came across while putting it together. Also, thanks to Sarah Rich for helping me with some crucial edits.

With so much focus on the US Government militarizing the US/Mexico border right now, it can be easy to miss the new types of migrant urbanism cropping up in the borderlands. For architects and designers, it’s a process that presents important questions, and great potential for innovation.

How can architecture reconcile the transborder pressures of providing adequate housing with the inevitable tides of hyper-immigration? How can it help manage the increasing sprawl of the destitute colonias swelling between the two countries? And how can we bring new models of planning and infrastructure to areas of booming migrant settlement? How can design help to preserve the cultural identities of (im)migrants, or even help in some way to secure their political status here in the U.S.? Can design facilitate ties between immigrants and local municipalities, while preserving their connections to their homelands? Furthermore, how can future migrant structures suture the dismal and widespread labor-scapes of poor rural America?

From cheap hotels to border crossing choke points, smuggler tunnels to detention camps; from temporary labor shack housing to urban homeless shelters; squatter encampments to life in a vehicle, thousands of deprived families squat perpetually between various nodes of borderzone nomadism. Could a solution to farmworker housing help resolve other sectors of nomadic urbanism, like homelessness, or emergency housing for natural disaster refugees? How might our focus on migrant structures address these populations, as well?

For example, Public Architecture explores how the proliferation of informal day laborer shelters that are popping up in the urban core could be designed to help dignify and institutionalize this laborer space. But perhaps these structures could also serve as a bridge with other communities who stand to benefit from similar projects, like bicyclists seeking bike shelters, or other labor activists looking for mobile stations in their own field deployment.

First, some quick economic context in order to better understand the farmworker housing issue and how it has played out in the evolution and development of a dispersed borderzone culture in the United States: Current estimates place the number of migrant and seasonal farmworkers in the U.S. today somewhere between 3 and 5 million. 61 percent of these people live in extreme poverty, with an average median income less than $7,500 annually, and a household income somewhere around $10,000, but not exceeding.

Bill Moyers, in 2004, ran a great series ‘On the Border’ which traced the plight of farmworkers in this country through the last century up to their current struggles today. The history of migratory farm labor in the United States began right after the Civil War “when agriculture became increasingly the domain of business enterprises rather than family or subsistence farms. Always at the bottom of the economic ladder” Moyers reminds us, “the migrant labor population was filled time and again with marginalized groups — the poor, immigrants and racial minorities.” His website goes onto emphasize the work of Philip L. Martin, a professor of agricultural economics at the University of California at Davis, who has tracked the tidal wave patterns of the migrant farmworker population, suggesting that during the 1920s there were some two million migrant farmworkers in the United States. By the 1940s, he claims, the number had fallen to about one million. Then, came industrial mechanization and the numbers fell even further close to 200,000 in the 1970s. With the advent of NAFTA, Mexico’s farming industry has faced considerable depletion since and in the last few decades the U.S. has absorbed much of the shift in agricultural output, which has drawn many desperate Latino workers across the border.

In general, employers don’t provide adequate housing, if any at all, and workers and their families are forced to seek shelter in multiple locations during the year, according to the Housing Assistance Council, “usually in small communities with very little rental housing available. Compounding the workers’ difficulty, low prevailing wage rates and limited days of employment have resulted in two-thirds of migrants living below the poverty line.”

The Rio Grande Valley in the south of Texas is the nation’s capital for farmworkers; 90% of the 1 million people there are Hispanic and approximately 1/3rd of those depend on employment in agriculture. The Migrant Legal Action Program places the housing options in two categories: “either on or off the farm.” On the farm, housing is provided, but employers impose stringent control, such as tall fences, “both to keep farmworkers in and to keep outsiders such as lawyers and health care providers out.” These facilities - labor camps, as they are called - are overcrowded and lack the most basic amenities - toilets, running water, and even electricity. On top of it all, this kind of shelter means a reduced paycheck.

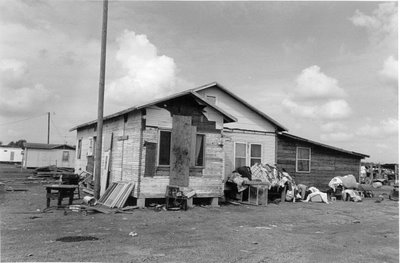

The “off the farm” option usually means makeshift shelters constructed out of scrap material from nearby ditches, open fields, abandoned buildings and cars — places dislocated from basic infrastructure, and generally perceived as countryside slums. The MLAP suggested in 2004 “that [at the time] there [was] only enough adequate shelter for 425,000 of the nation’s 1.2 million farmworkers.” Or, about 35%.

In terms of demographics, migrant workers circulating in the United States “follow three general streams. In the East, workers begin in Florida and travel up through Ohio, New York and Maine, following crops that range from citrus to tobacco to blueberries. The Midwestern stream begins in Southern Texas and flows north through every state in the MidWest. Workers in the West begin their season in southern California and follow the coast to Washington state or veer inland to North Dakota.” (pdf) The majority of farmworkers are located in Florida, North Carolina, Texas, California, Michigan, Oregon and Washington.

Along the border, the lower Rio Grande Valley, for instance, is a four-county area that forms the southern tip of Texas and has a population of approximately one million people. According to the organization Migrant Health Promotion, “Nearly 90 percent of the Valley population is Hispanic.2 [And…] The Valley is the permanent home of one of the largest concentrations of farmworkers in the United States; roughly one third of the Valley population depends on employment in agriculture.3” More interesting is that the Valley population grew “an average of 31 percent across counties from 1999 to 2000, compared to 13 percent nationally; yet the region has substantially higher poverty rates than Texas or the United States as a whole”.

Their research goes on to conclude that for residents without specific skills or training, work is very scarce in the Valley. “Thirty-four percent of the entire Valley population lives in poverty compared to 15 percent of the Texas population and to 12 percent nationally. Unemployment rates in the colonias are two to three times state rates, and many sources cite rates up to 60 percent.”

For those who don’t know, colonia means neighborhood or community in Spanish. But, along the U.S.-Mexico border, MPH explains, “colonias are unincorporated and unregulated neighborhoods where lower-income families build and own their own homes. They may or may not own the land.” šAnd in general, I have heard they rarely do. The majority of these communities can be found in Texas, New Mexico, Arizona and California. Texas, unsurprisingly, has the largest number of colonia residents with 400,000 to 500,000. “The Valley alone is home to nearly 2,000 colonias and the bulk of the Texas colonia population. Valley colonia residents are predominately Mexican and Mexican American (99 percent).

Interesting facts, and certainly important while baring in mind the Rio Valley is incredibly polluted due mostly to the expansion of maquiladoras, and considering that the U.S.-Mexico border is expected to grow in population by another 10-15 million by 2020. The combination of this population explosion, the incorrigible sprawl of maquiladora by-product, and a continual expansion of the colonias, could spell a major disaster for the Valley in the coming years. Not to mention the impact of increased border security and how that will influence border crosser patterns in and around the Valley, and how constant patrol may interfere with the natural ecology of the region.

Design Corps, a community-design based architectural outreach and planning organization, has worked in close collaboration with low-income populations since it was founded in 1999. One of their primary projects has been the Farmworker Housing Program, which has helped farmworkers devise their own affordable housing in Florida, North Carolina, Virginia and Pennsylvania.

In 2004, Laura Shipman, an advisory Board member of Design Corps, worked with farmworker advocate, Rob Williams, of Florida Legal Services, to design hurricane-resistant housing just after the storms ripped through Florida and devastated much of the already substandard farmworker housing there. The project dealt with specific concerns, like balancing shared housing and communal space (washrooms, TV rooms, recreational spaces, and other community plug-ins) with the need for private and family-friendly areas.

Housing located directly on the farms requires structural elevation and hurricane-resistant features like retractable window panels and back-up ground fastening functions, so ’security’ and ‘openness’ can be equally central to the design. Most important perhaps, is that the end product can be a place which helps overturn the traditional perception that farmworkers only live in run-down shanties.

Design Corps has always treated its clients (often society’s most underserved people) as guides in the process through questionnaires, interviews and charettes; and by establishing a genuine and lasting relationship, which stimulates the community’s own design sensibility and input. Shipman’s project (pdf), while responding to the disasters of Florida’s post-hurricane landscape, is intended to be a model of community design for non-profits working with farmers and migrant workers all over.

Bryan Bell, the founder of Design Corps, who has been doing migrant housing for twelve years, was also featured in Metropolis back in 2004, when he spoke about the process. Specific needs, “which may not be uniform amongst farms around the country,” are teased out in many ways. He says, for instance, “Instead of trying to rewrite migrant housing law, we just do strategic strikes. Like in South Carolina, one of the farmers had used bunk beds. Now, some 48-year-old farmworker shouldn’t have to climb up into a bunk bed. So we put in our lien, ‘No bunk beds.’” Bell proves that design and architecture can provide a bargaining chip for workers seeking to improve their conditions with farmers.

The primary goal has been for housing “that accommodates diverse cultures, counters the stigma associated with farmworker housing, and provides flexibility in configuration that allows for long-term use.” Design Corps’ website, also boldly states, that “while the manufactured housing industry has gained ground in middle- and upper-income markets, it is important that the industry continue to develop its original client base, low-income households, with better products and improved image.”

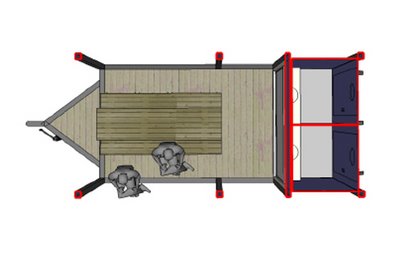

Another project that was recently shown at the Mobile Living Exhibit in NYC is the Resident Alien, by designer Andrew Dahlgren, a student at the University of Arts. Considering the fact that most migrant workers “find work by word of mouth,” says Dahlgren, and “travel in small groups, from farm to farm with little to no personal belongings,” an ideal solution would be a dynamic and configurable nomadic unit made from standard cargo containers. Dahlgren’s solution (pictured also at the beginning of the article) involves three modules (kitchen and eating, social space, and a bathroom) that could be installed into the containers, or in the beds of semi-truck trailers, and would allow the workers to travel and dock in designated areas around the farms to form their own community configurations tailored to specific conjoined needs.

The architecture becomes a poetic response to fact that migrant workers are “in a way ’shipping’ their lives, belongings, and homes across the country.” And because the units “can be pulled by a truck or van and could be purchased by the workers themselves,” the Resident Alien gives workers a sense of ownership and control of their lives in a context which would otherwise treat them as nomadic serfs.

As spatial translations of global labor grind against an ironic nexus of free flow capital, how might an ideal migrant structure effect the global economy? What can farmworker housing achieve as a form of architectural negotiation with the fetid landscape of globalization’s open (and closed) borders? Can architecture help leverage migrant needs in the harsh marketplace of exploited global labor?

There are many other projects worth mentioning where migrant worker housing is resolved by the creation of affordable housing in general; a Google search pulls up some recent examples: Amistad Farm Laborers Housing, the Kingston House. Some are partially funded by the government’s assistance program, established solely for the purpose of developing farmworker housing, but those amount to a very small portion of what is actually needed.

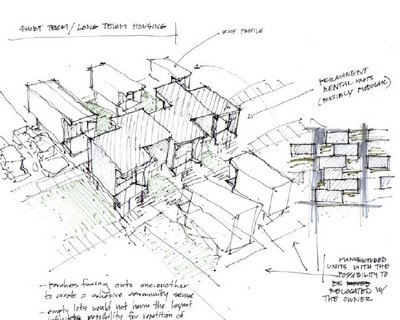

And, of course, Teddy Cruz out of San Ysidro, California, has been mentioned on Inhabitat before, for doing some of the most important work in this context today, with implications for affordable housing well beyond the borderlands.

But what about all those workers who aren’t fortunate enough to find adequate rental housing or decent employer-provided accommodations? Hopefully, these projects can help suggest ways to alleviate struggles for millions who have come here to seek a better life for themselves. Perhaps, as simple as it may sound, part of the solution for everyone may very well begin with some thoughtful and decent farmworker housing.

3 Comments:

Interesting article, Bryan. But it seems to me that the upshot from all your examples is how much has been planned but how little has been built.

Certainly, the developments you have cited are interesting and worthy. But I'd like to ask a radical question: is design part of the answer, or does it simply add to costs and thus create a need for subsidies?

After all, according to the MHP web site, the colonias are moving forward, albeit slowly: "Many colonia residents have organized over time, incorporated their communities and gained access to more services. The 1995 Colonias Fair Land Sales Act offers some protections to residents relying on contracts for deed to finance property, assisting in residents' efforts to bring roads and utilities to their communities."

Perhaps organizing, community building and political action are a more sustainable and affordable answer answer than high (or low) design of migrant structures.

Rob

No question, the most valuable thing of all is self-organizing, getting these communities to take it in to their own hands, etc. but that doesn’t mean design cant have a part in helping that process.

Design Corps has actually built quite a bit. Check out their site, many projects, from housing to bathhouses, sometimes small projects can actually make a huge difference, helping workers to negotiate with farmers, helping them to establish new living standards, farmer requirements. The act of producing these projects can help these communities come together and organize where perhaps before they were in disarray and without focus.

I feel your sentiments, as always, representing the communities representing themselves.

I don think that design is any sole solution, nor do I advocate for it to provide some savior product for the underprivileged. And I certainly do not overlook the value of community building, self-organizing, etc., people mending their own conditions. I am only trying to find ways in which design can help, as a supplement, not because I think design is the answer, but can design, just play a role. Does it have a place in the progressive community building of migrant settlements? Should designers be searching for ways to help, not in a way that ignores the independent solutions of communities providing for themselves, but quite simply: can design help push progress further along, can design help enable more community building, can designers provide things that help sustain activism, help to build infrastructure that only helps the communities better organize and devise their own infrastructure? While ultimately I hope so, and I hope that it can be done so for the sake of community building, I also ask the question of the design field: isn’t it important for them to try to become more involved? For the sake of design, shouldn’t designers be willing to do more political work? Get more involved directly, and instead of auto-perceiving design as an arrogant and alien effort, is there a genuine place for design to assist migrant settlement community building?

i think many of the solutions to this landscape are already being improvised and activated by the communities who live there themselves. And, certainly they should be leading the efforts. Activism, organizing, self-building is critical to any progress, but like design, those aspects are only capable of doing so much as well. So how can communities and designers work together, rather than suggesting one more so than the other. What projects can illustrate collaboration, partnership?

I see your point about design burdening the situation with costs and subsidies, but I think design in that sense can become a conduit for getting investment into these places that might not otherwise go there. Certainly, we want to see these communities be self-reliant and independent, but perhaps design projects can break ground into bringing in outside funding that could have a big impact that might normally never even be considered.

As always though, I super appreciate your insight and reminding me of the importance of community self approach and often times the impotence of design.

b

The idea has to come first. Keep up the great work, we need people with the vision, best wishes, The Artist

Post a Comment

<< Home